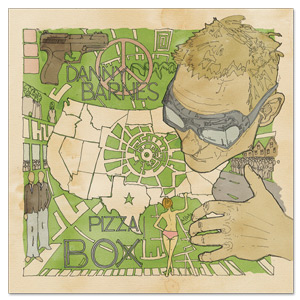

At age 47 and with well over 50 recording credits under his belt, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Danny Barnes believes he just put out the best material of his career in the form of Pizza Box, an eleven-track full-length released on ATO records and recorded at Dave Matthews Band’s Haunted Hollow Studio in Charlottesville, VA. Barnes toured this summer with Robert Earl Keen, played with Yonder Mountain String Band this fall and will open dates for Keller Williams next month. The banjo player also appears on a few tracks from DMB’s latest, Big Whiskey and the GrooGrux King and has played several live gigs with the band. Barnes spoke to jambands.com about his relationship with DMB, where he gets his diverse musical inspiration from (Stravinsky to Wu-Tang) and his insightful opinions on the state of today’s experimental state of the music industry.

You were on tour with Robert Earl Keen this summer, you’ve been on tour with Yonder Mountain String Band since Sept., your new record Pizza Box came out in Oct., and you’re scheduled to open for Keller Williams next month. It’s been a pretty hectic year, what are your thoughts on all of that?

I’m thrilled to have a good job, I’m really excited to have work. I’m 47 years-old and I’ve been working on this since I was 10 and I’ve spent millions of hours working on what I’m doing, I’m excited to be where I am. It’s great to get up in the morning and be excited about your life and to love what you’re doing and the result you’re getting. It’s pretty awesome.

How did you get involved with Robert Earl Keen?

I’ve known those guys since I was a kid. Before he was known as a writer he was just one of the acoustic guys in Austin, one of the bluegrass guys I grew up with in the area. We had mutual friends and went to festivals, and I played in bands with them. I just knew those guys proximity-wise, but I didn’t really record with them too much. My friend Rich Brotherton was producing the record and asked me to play on it, so I did. We had fun and I started touring with them quite a bit and then I played on another record with them, did a DVD with them and have done quite a few shows with their band.

You also have a relationship with Dave Matthews, I read that he picked the album title, Pizza Box; he sings on three tracks on the record and he hooked you up with the producer John Alagia. How do you think the support Dave Matthews Band has given you has helped your exposure?

Well that brings up two different subjects: one would be exposure in the numerical sense and the other is just inspiration, and I’d like to address both of those. As far as exposure, the real trick in music or art, are the people that don’t know about what you do. It’s one thing to play to people that know what you do but it’s a whole other trick to access people that have no idea who you are. And that’s where all your growth comes from is through other people, through lines that you draw professionally, or just other people who have no concept of what you’re doing, so I think much of the numerical attention to what I’m doing, that stuff is exponential. That’s just the thing that happens in music.

If I go play a show for Bill Frisell, there are people that learned about him through me and there’s people that have no idea who I am that learned about me through him, that’s just the mechanics of the business I think. We make friends in music and even though his fanbase is the size of a third world country and mine is like a platoon [laughs], nonetheless, these are subsets. Regardless of the numerical components they still are sets, and they have places that they intersect and I’m thankful for all of those lines that happen.

Just being able to play with them on their record puts me in front of a lot of people who have no idea what I’m up to, and I’m sure there will be people that won’t dig it, but there’s a certain amount of people that are going to dig what’s happening and hopefully they’ll buy the record. The goal is that they’ll tell other people word-of-mouth-wise, but going back to the inspirational thing, it’s funny, I’m an underground person. I’ve been out there since the mid ‘80s and most of my fans are musicians. When I get fan mail, typically it’s somebody in a band, and sometimes it’s a huge band and I get fan mail from guys that are in these big bands that say, “Your record is great, I listened to it in the car and I really dig it.”

That part of it, just going to the inspirational part of it, is the fuel I really run on because I’m an underground kind of person. Most people that know about me are artists or musicians and they’re not mainstream individuals, and that part has been very inspirational to me because I look up to these guys, and they say that I did really good on that record. It lets me know that I’m onto something and I’m working on that batch of songs for that record, and I worked on that for about three years. I’m not talking about having it in a notebook, I’m talking about really working, about developing the poetry, where the elements are very simple but have bolder things that are happening. I kept playing this music for different people, like Robert Earl Keen for example and Dave [Matthews], different writers and composers trying to find out if I was getting somewhere with this. And as I worked, the more and more people were saying, “I think you really got something here.” That really helps you focus because you realize you can worry about execution instead of developing the principal idea.

When I was working with Dave on his record down in New Orleans, when we had some time, one thing I do with my friends is we pass around guitars and play new songs that we’re writing. Mainly fragments, but that’s really what we do. I could tell from talking to him, he would stop and be really clear and say, “You’ve really got something here, this is starting to sound really good.” As I started to get that same reaction from some of my friends—I really look up to these guys that can really write songs that can really make things happen and really entertain people—those guys are my heroes. So just the inspiration from any guys in the band like Carter [Beauford] and Rashawn [Ross], they just kind of let you know. They go out of your way to tell you that you did really good with that, and they’re not buttering me up because I’m way down, I’m underground, they have nothing to gain from it. It lets me know I’m on to something, it’s worth pursuing and this is worth sacrificing, I made a lot of sacrifices for this work, learning to play and developing ideas and sometimes you kind of wonder—am I doing the right thing?

Sometimes it’s tough, like even your job, it’s a little harder today than yesterday. So just the support of those guys, it means so much to me. If I go play banjo with Robert Earl Keene on a tour, I get to play for a bunch of people that have no idea that I exist, and if I play with Dave Matthews Band and there’s 25,000 people, there’s probably only 800 people that could spell my name or pick me out of a police line-up. Ultimately, I don’t pursue those kinds of things as a mechanism to get what I’m doing out, what’s really happening is my friends saying, “Fly out to L.A. and play with us at the Hollywood Bowl.” Those guys are my friends, so I suppose I could be criticized for trying to promote what I’m doing, but it’s really my friends saying, “I really want you to play on this record, I really think you should come down to New Orleans to hang out and play on this record.” It doesn’t generate from me calling them up and saying, “Hey man, it would be really good for me if you let me stand next to you while you got in this picture you made.” I really don’t think that way, I’m not wired like that, and I just write music and play. I’m fortunate enough that it comes from people saying, “I want you to be a part of this.”

No Comments comments associated with this post