There was a pause. An all-female percussion ensemble echoed from the stage, through the walls and over the free-beer table towards where I was sitting backstage. I coughed. There was another pause.

“I have a hard time saying no when it’s late at night. It’s like, ‘I’ll just sleep tomorrow, a few hours before the gig.’ But you never do, you know?”

“I do know,” I said. “Then the nerves start to feel like a live wire. You can feel the platelets scrape the vein.”

“Right? But then you have to know the blues to sing the blues.”

“What?” I said. “Come on, that’s cliched.”

“I know,” he said. “But it’s true.”

“But I guess writers do it to. How many have called it quits? Just run that razor’s edge for as long as they could and then put their brains in the orange juice.”

“You have to put yourself out there. It’s my story, it adds originality to it,” he said. “I did something terrible, I experienced it and now I get to express it to somebody in maybe a perspective that no one else thought of.”

“And isn’t that the bitch of it though, that many times you have to suffer for what you do. You have to hurt to write a love song. Look at Hamsun’s ‘Hunger’ or half of Bukowski’s work. They went all the way down and once they’ve gone all the way down…”

“That’s the thing, I think a lot of musicians do this, I know I have. It’s almost like you sabotage your own life on purpose. Sometimes you sabotage yourself so you can do that.”

I turn the tape recorder off. It’s an old interview, from last August, from the days before the road. From before this bar counter and this frozen Pennsylvania winter on the river.

I wave to Phil. He peels himself off of his forearms and away from his paperback. He pours me another pitcher and leaves the barroom. Hopefully to get my chicken wings. Breakfast.

The notebook next to me is a bloodshot diary of those August days on the road. A scatterplot of scenes, ideas, scraps of conversation. Interviews. Notes on this interview that I am listening to. Old coasters and napkins with ink-bled scrawlings poke out of it. The back cover is torn in half. I pour myself another and look at the page in front of me trying to decipher the original ideas so I can match them with the conversation on the tape recorder.

I’m trying to piece together a story of a ghost out of what had been flesh through this beer haze. It’s day thirty-six of this and I’m tired.

The chicken wings come into Applejack’s bat cave of a bar. This subterranean lair of dirty lines of ice blue speed done by bikers in the bathroom, of pool cue hookers and weekend warriors down from New York City trying to say they ride. Last week, a couple on a brand new Harley in brand new leather chaps got off their bike in the lot as I smoked a cigarette. The woman riding bitch had her nose taped up with a new nose-job. She didn’t order the wings.

But they’re good wings and looking at the grease stains tattooing the open page of the notebook I am reminded of the barbeque that made them. I had it in August at the blues festival outside of Baltimore. It was good barbeque and I didn’t have much beer in me; I had work to do.

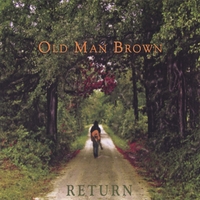

I arranged the interview with Old Man Brown’s lead singer months earlier from Kuwait. It was February and I had endured nearly a month of sandstorms, bootleg date-rum madness and the sad eyes of the Chinese hookers that hung out of the windows behind my apartment. Any good traveler knows that if you stay in one spot for too long, the initial euphoria gives way. It changes to a dark pockmarked madness that feels something like walking down a steel tunnel as its sides are beaten with bone clubs. Hemmed in, hurting, I took solace in the few albums I brought along for exactly that type of time. But one began to get played more than the others, edging them out slowly, making its mark as a part of my daily routine. Old Man Brown’s Return kept buffering the walls of defense against the tunnel. It provided some kind of salve to the blasted wounds of the night.

Return was recorded in 2006 in Nashville at Johnny Neel’s home studio. Done in ten days it was inspired session work. Neel, the former Allman Brother and current leader of the Criminal Element, heard about Old Man Brown through a friend and invited the Baltimore band down to Nashville to record their first album. Neel couldn’t have been a better match for the band, as their Allman Brothers-and-Bill Withers-bastard-child sound dovetails nicely with Johnny Neel’s penchant for soulful and funky roots music. Old Man Brown cut their record then cut their teeth on the road in the DC and Baltimore area with Neel joining them on keys at times. They made waves in the area and their album got decent local airplay. It got damn good reviews. “Return” made its way to me through my brother who had stumbled across Old Man Brown playing at an old hotel in the Fells Point area of Baltimore.

“You have to check this band out,” my brother said. “They’re incredible. Funky, man. Funky. And they can tear the roof off a place when they jam. We’ve been looking for this for a long time.”

He was right. I couldn’t stop listening to Return after I got it. Everything that I love about music was falling out of the notes and songs. The lyrics were well crafted and hit home in all the right places. The arrangements were intelligent yet organic, the solos phenomenal. It moved me, there’s just no other way to say it. And, I could dance to it. They cut a groove fault line deep.

No Comments comments associated with this post