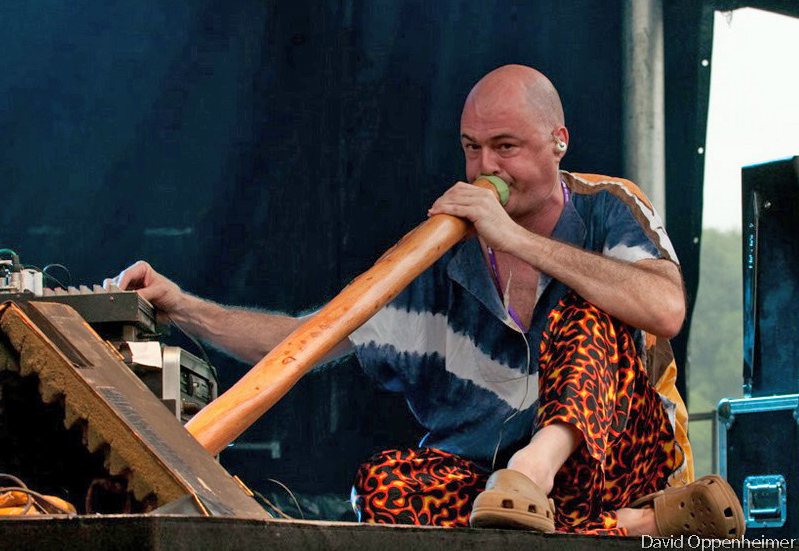

Graham Wiggins, aka Dr. Didg, plays a 1500-year old Aboriginal wind instrument called a didgeridoo – traditionally a long piece of wood hollowed out by termites. Utilizing looping effects, he leads his improv-heavy rock band into magical realms of danceable bliss, spicing up the modern musical recipe with an ancient and unusual flavor. The good doctor is serious about merging the past with the present, having earned a PhD in physics from Oxford before living with the Australian Aborigines to master their techniques.

He launched his music career with the powerfully gorgeous acoustic band Outback in the late ’80s before forming Dr. Didg in the ’90s. After several years on a scientific hiatus, the band re-emerged at this summer’s All Good Festival and is currently gearing up for gigs at Ace of Clubs in NYC on 12/16 and The 8×10 in Baltimore on 12/17.

Dr. Didg spoke with Jambands writer Paul Kerr about the spiritual aspects of his instrument, the relationship of physics to music, sitting in with the Grateful Dead, and the creation myths and dreamtime stories of the Australian Aborigines.

The didgeridoo is a very unique instrument. Is it basically one note that you have to work with?

Yeah, in the standard way of playing it you’re basically manipulating a drone on a single note. There’s one or two higher notes that you can play but you just use those as a kind of percussive emphasis. It’s interesting to me, cause my two main instruments are the didgeridoo and the piano, and they’re such polar opposites. Because a piano you have 88 keys but they all basically sound they way they’re going to sound, there’s not much you can do about it. A didgeridoo you have one note but the sound is everything, the flexibility of the sound and the way you control it.

Do you find that to be limiting or freeing?

It is limiting but – I think you would find this is true in a lot of art forms – that it’s pushing against the limitations is where the creativity happens. It certainly forces the music into a new and special kind of space. Particularly cause it’s almost physiological. The didgeridoo, the primary aspect of playing it is circular breathing so you can keep the sound going continuously by storing air in your mouth and then pumping it out through your mouth while you breathe in through your nose. It means the rhythm has to be tied fundamentally to the in and out of your breath. If you get the music too far away from what is physiologically sensible you find you just can’t do it. I think it probably makes it very danceable because the didgeridoo is tied to the cycle of your body and you can’t just arbitrarily pull a rhythm out of the air. You have to do something that is already a dance within your own body, and I think that communicates through to the audience as a quite infectious kind of rhythm.

It’s traditionally an instrument meant to have dancers along with it, is that right?

The main thing that would go with it is a singer. The Aborigines, in a traditional setting, they don’t play the didgeridoo on its own. They only understand its purpose and what you play on it as it relates to the singer and the song. But in those ceremonial settings dancers are a key part of it.

Are you able to play the didgeridoo and piano at the same time?

I’ve tried it but I find what happens for me when I do that is I play both of them half as well.

Can you play high notes at the same time as a drone, like Tuvan throat singers who sing multiple notes simultaneously?

No, it’s like playing a bugle. You can push your way up a series of notes that are higher resonance. For the most part you have to choose. You’re either playing the drone or you’re playing the high note. What’s interesting and one of the things that I only learned after many years when I finally got to play with the Aborigines, is in the traditional technique there’s a way of sounding the higher notes so instantaneously that it doesn’t sound like the drone ever stopped. When I had heard it on recordings I thought that there was a guy there with a drum and then I read the liner notes and they’re like “This is a solo didgeridoo player.” Finally I was able to work out how to do that.

It involves a tonguing technique that is related to sounds which only exist in the Aboriginal language which are technically called interdental consonants. So like we would say “t” or “d” they have a similar sound but the tongue goes between the teeth when they’re doing it. And you have to do that in a particular way while blowing down the instrument to instantaneously flip the sound up to this higher note and pull it straight back down again. And then in terms of more analogies to the Tuvan throat singing, what you do on a didgeridoo as well is to sing. And so then it does become very polyphonic. You sing a different note then what you’re playing with your lips – typically an octave plus a major third – and all these extra harmonics start to come in and the sound gets really rich. You can also scream and move your voice around wherever you want.

They do a lot of traditional animal noises too.

Yeah, and it goes deeper than that in that what they’re aiming to do with a didgeridoo is to illustrate the story in the song. But the illustration can be obvious in that “Oh, they’re singing about a dog,” you make a dog bark. Or it can be a lot more subtle, in that they’ll sing about a snake and try to make a rhythm that undulates the way the snake moves or that bounces they way a kangaroo bounces. You can illustrate in the rhythm the movement of the animal. And when you’ve got the dancers who also do these very uncanny imitations of the animal they’re singing about, also trying to illustrate the song, it’s happening on many levels.

What I was told when I was studying with them was that they’re not just singing about an animal, they’re singing about the animal ancestor. It’s part of a ritual story, a dreamtime story, where they’re trying in a way to summon that ancestor up. It’s not quite like a possession. In Africa you get these possession trances where you go into a state and then the ancestor lives in your body for some time. It’s not quite that extreme but they’re trying to summon that ancestor to the proceedings and get his attention and they do that by trying to bring him to life in the sound and the visuals of the music.

How long did you spend with the Aborigines?

I lived with them for three months. I went to a place called Elcho Island which is off the North Coast [of Australia] and it’s a place where they’re still keeping the traditions.

Do they use the didgeridoo for instrumental music or is it always with a singer?

Always with a singer and also generally only in the ritual setting. You wouldn’t see people just sitting around and playing for fun. It’s mainly that there’d be a reason, particularly funerals when I was there. Somebody died, they’d spend three weeks every day going through a series of songs and trying to put the spiritual world in order in relation to this person’s death.

Did you encounter a lot of resistance from the more traditional folks?

That’s an interesting question because there is a little bit of touchiness about us white folks playing it. I’ve found that if it comes to you at all, it usually comes from people who are very political and not necessarily living the life themselves but who have taken a stance and want to make a statement about the condition of the Aborigines and the ways they’ve been taken advantage of. And so they’ll say “White people don’t deserve to have this art and this music that you don’t understand. It’s ritual and it’s sacred for us and you should leave it alone.” And then I go to a place where they’re living the tradition and they say “Sure, come on, we’ll show you how it works” and they’re very open about it. And in fact from their point of view, they said “If you’re going to do this, you ought to know where it comes from.”

Cause up till then I had invented my own style. I listened to what they were doing and had no one to teach me, I just had to try to imitate those sounds. And then I tried to make it sound like the Grateful Dead or Afro-Cuban jazz which were really my rhythm influences. So that was a perfect opportunity. That’s exactly what I wanted was to know where it comes from and the more advanced techniques that I’d never worked out. But it was a double-edged thing. They said “You should know where it comes from” but they also didn’t want for me to take that skill and go do a kind of traveling dreamtime show where I would say “Ladies and gentlemen, here’s an evening of their culture.” Then they’d feel like I was ripping off their stuff.

No Comments comments associated with this post