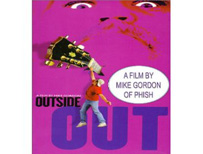

Today we look back to February 2001 and this conversation with Mike Gordon following the release of his film Outside Out.

Mike Gordon is an interesting cat, that much should be obvious from his bass playing. He’s a musician, writer (author of “Mike’s Corner”, a collection of esoteric vignettes published in 1997), and – now – a filmmaker. While all of these projects are in very different mediums, there is something genetically related about them, the same spirit manifesting itself in different forms. Like other musicians who have translated their visions literally onto celluloid – Bob Dylan, Frank Zappa, and Sun Ra, for example – Gordon’s initial effort doesn’t always succeed, though it does harbor a dazzling array of information about the creative process. It’s also damned entertaining.

It struck me as pretty humorous that when the chance finally materialized to interview member of Phish, I wasn’t even really allowed to ask about them. Well, it was more a polite request than anything else. And rightly so: they’re not what’s going on right now. I can’t say that the question, the big question – “what the hell is up with Phish?” – wasn’t on my mind. It was. Sort of. The answer, though, was obvious without having to ask: when it happens, it happens. So, we talked about the strange worlds of “Outside Out”, a surrealistic tale of a young guitar student (Jimi Stout) and his cosmically touched instructor (Colonel Bruce Hampton, [retired]).

JJ: How would you describe Outside Out to a film geek?

MG: Do you mean a buff?

JJ: Yeah, a film buff.

MG: It’s very experimental. I don’t know if I’d use a different explanation for the film geek as the normal person. Experimental, homemade, but with 5000 hours of work; with a story, but the story not being the major charm.

JJ: What would you describe as the major charm?

MG: (Laughs.) The major charm. The strangeness of the world that the characters live in, and something about the style in which it was put together. I’m being vague. I don’t know. I guess that it’s just that you can tell that it was a labor of love.

JJ: The film has a pretty unified look and feel to it that’s pretty different from a lot of what’s out there. Were there any specific ways you went about getting that look?

MG: Well, we shot on video, for one – high quality video, Beta-SP, actually – and transferred to film and then went back to video, from the film. First of all, that creates, technologically, a certain kind of look. The actual video master itself, before the film, was a lot more accurate in a lot of ways, but we liked the look of the film. I was working under certain constraints, like he [Ricky/Jimi Stout] always wore the red shirt because of continuity reasons. We were trying to fit in some earlier filming with some later filming. There’s kind of a lot of red and blue — red, white, and blue, actually. There’s a lot of it. I was working within certain means. It was low budget, ‘til the end.

JJ: Was there anything else with the art direction? The sets all seemed pleasantly surreal in a real specific way.

MG: I like surrealism.

JJ: Noticed.

MG: I just go for the surreal. I like things that are realistic but a little bit warped in a certain way; subtle but deep ways. We did a lot of blue-screening, where you act in front of a blue screen and then the blue is taken away and another scene is put in where the blue was… for people who don’t know. There’s a lot of that. There were certain gimmicks like that were used a lot. There’s a lot of certain sound effects and dream sequences. It’s kind of like… there’s sort of a pile of concepts that don’t necessarily relate to a strict reality.

JJ: Sort of related to that: how would you describe Col. Bruce Hampton to a civilian, or just to someone who didn’t know him?

MG: I’ve used different ways. I’ve said “a Southern Buddhist Colonel”, or “the personality of a one-year old in the body of a 55 year old man”, “someone who’s held on to their child’s eye”, maybe “someone who’s done a little bit of everything from music to acting to stand-up comedy to accounting to race-car driving”. Sort of a hard to pinpoint guy, just in that you don’t know if he’s toying with you or not, whether he really has extra senses, supernatural abilities.

JJ: Did having Bruce and his musical philosophy at the center of the movie dictate any of the experimental techniques you used?

MG: Well, I guess… I don’t know. A lot of the actual way it was filmed and edited – the look – probably becomes from my own experimentation. Do you have the VHS or the DVD?

JJ: The VHS.

MG: On the DVD there’s some extra footage. One thing there is this four minute film I made and sent to Bruce, which inspired him to make a film with me someday. The four minute film is his hand moving in slow motion, for most of the time. It’s a little experiment. Experimenting with film techniques probably just comes from me, although Bruce is the right kind of character to bring into this world that’s somewhere between reality and the absurd.

JJ: Do you differentiate between those techniques and more conventional story-telling methods, or filming methods?

MG: For starters, I haven’t had a lot of experience writing stories. I’ve had more experience doing weird experimental stuff, which is why that becomes more significant than the story in some ways — at least, a few respectable people have said that to me, and I believe them. (Laughs.)

Another thing, that I think I talked about somewhere… oh, I know where: part of the web site. There’s this little statement that I, somewhere, wrote out. I was talking about how one thing about a story is the protagonist is supposed to be challenged in big ways and is do a lot of things to help themselves, but with this sort of semi-pseudo Buddhist perspective, it’s not so much about taking such obvious action. Bruce’s philosophy sort of stems from the idea of just existing, and being in the moment. If you’re existing and being in the moment, then you’re not being proactive in the same way as someone who’s a go-getter.

In the movies, I think it was Woody Allen or someone, said “we go to the movies to see people do things, because in real life we don’t do things”. I think that he doesn’t really get challenged quite enough, or do quite enough, in terms of the story, but I just kind of… I sort of like David Lynch’s concept, which is: you just start making it and you get into the world of the film and then it dictates itself, it writes itself like a poem, if you let it. Certain things are thrown in, even certain part of the story are worked out, just because it felt right.

JJ: That said, did you write anything for Bruce or any of the characters that dictated who they became or did you let them run free?

MG: That’s a good question. There was no screenplay, but there were pages and pages of notes, like 30 pages. Within those notes, there was a shot list, and – within each shot – there was, just about, all the dialogue — not verbatim how they would say it, but all the concepts I wanted to get out. I thought that improvising would be more natural. In retrospect, improvising is more difficult. And, besides, I came up with all their lines for them anyway, on the spot. (Laughs.) I learned a lot. The whole thing was a real learning experience.

I pretty much told everyone what to say, even Bruce. Bruce has this line, a couple of lines, in “Sling Blade”? The movie?

JJ: Yeah, the band scene.

MG: Yeah, and in one of them he reads that poetry stuff, like he’s the poet/lyric writer guy. He just spews off this stuff that’s very Bruce-ish, and I assumed that he had just come up with that himself, but he said that Billy Bob [Thornton] wrote it for him, just knowing Bruce… which is sort of the same thing that I did.

I started off with a whole bunch of concepts, terms that Bruce had used – like the vomit, or whatever – and then encouraged him when we filmed the guitar lessons, which were just random days of guitar lessons, to just use these concepts and play with them. There are a couple of things – like the monologue when Rick first arrives at his house – that he did without any prompting at all, I wasn’t even rolling the camera. He just started doing it, and I just rolled the camera. That’s a good little monologue, the weird thing. Other than that, I pretty much told him what to say and he just said it in his own way, for the most part.

With the other characters, the same sort of thing: they sort of ad-libbed and went off on concept but I was sort of figuring out what worked on the spot. There was a lot of planning, but a lot of improvisation also.

JJ: Did any of this grow at all out of the “Mike’s Corner” vignettes or stories?

MG: Those little vignettes are so much more visual than narrative, I think. For me, it just starts with some funny image and then I just write some things down to match it, to go along with the situation, the image. I like the idea of trying to keep that same sort of tone going in movies. Some people have said that I’ve sort of done that, like, if you like the “Mike’s Corner” book then you probably have the right sense of humor to appreciate the movie.

I don’t think it was conscious, but I had thought of that. The “Mike’s Corner” book was a compilation of stories from my whole childhood and everything, old stuff. But, when I directed the video – the “Down With Disease” video, the MTV video – the band thought that it didn’t have the Mike stamp on it enough, because there were too many people working on it when it was done. Everyone seems to think that, whether or not you like the film, it definitely has “Mike” written all over it. (Laughs.)

JJ: (Laughs.) I’d definitely agree with that. Why did you choose to use untrained actors or local actors?

MG: It was partly of because the way the project grew, the same reason it was shot on video. The original goal of the project – it was going to be called “the Outstructional Video” – was going to be Bruce looking into the camera, no other actors, just some spoof on playing guitar. That was the original concept. So, I went down and just filmed the guitar lessons, but – between coming up with the original concept and going down – I decided I wanted there to be a student. Bruce showed up at the airport and there was Jimi with him – he was Bruce’s tour manager – and I asked him if he wanted to help move lights and, on the side, be in the movie.

I was getting more and more into the concept of there being a story, so – for the next year – I came up with the rest of it, based more on the life of Jimi than Bruce, and I thought that would be sorta cool. And Bruce didn’t really want to travel as much either, so it worked out to concentrate on the life of the student. Originally, it was just a whole bunch of guitar lessons, just randomly done, and then pieced together.

Then, what I was going to say, the original goal was to learn how to use my new video equipment and editing system, the Avid system. When the film started growing a little bit, I still thought it was going to be a lot smaller of a project than it ended up being. There were these funny people that I know — and I always liked the concept of taking some funny people that I know and have them try to be actors. It was fun for me. I’ve done a lot of verite, I guess you could say, more from the real world. I feel more comfortable in that situation.

But, with all that said, I think next time, I would have a script, I would shoot on film, and I would have real actors.

JJ: You’ve mentioned before that you’re thinking about doing another film, and you’ve got this chunk of time off now, do you have any specific plans?

MG: Yes and no. I’m just trying to prioritize some different projects, and I want to make room for the most important ones — that being one of the most important. That would be the film project I wanna do, and the rest would be music projects. But there are other projects which are also interesting that aren’t quite as high-priority. I’m trying to figure out what I should be spending my time doing. I haven’t allocated all the time yet. Not too specific. I have a lot of specific ideas that I’ve had for years for the next film, but they haven’t solidified to speak of.

No Comments comments associated with this post