Mason Jennings is on the road through the end of October in support of his recently released new album, Minnesota. Named after the adopted home state of the musician, the nine-track work features Jennings in, perhaps, his most introspective form, but also mastering a collage-like sound that allows the man the ability to pull in a range of unique imagery and instrumentation without sacrificing his thematic arc. In short, Minnesota may be Jennings most personal and best work to date.

Jambands.com sat down with Jennings on the eve of the album release and while he prepared for the bulk of the rest of the dates on his tour card. Jennings’ debut self-titled album came out when the artist was only 22 in 1997. Now 36, Minnesota resonates with a rich profound afterglow by embracing ideas about family, love, alcoholism, and the light at the end of the tunnel after a long journey through yesterday’s often bleak and diffused environment. Cautiously optimistic and somewhat settled, Jennings offers a portrait of someone who has a firm and wise grip on the delicate balance between being an engaged family man and an astute artist who develops through the years.

RR: Tell me about the importance of recording this new album in Minnesota.

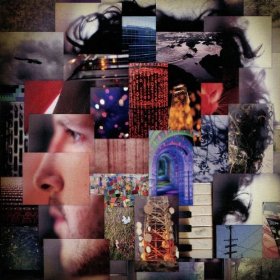

MJ: For this record, I spent a year collecting songs. I recorded about 35 different songs. I mostly did them all by myself in my studio out here. It was definitely the most eclectic batch I’ve had. The songs were just stylistically all over the place, so I edited them way down, and went with the idea of a collage-based record where it had every song holding its own space on the record. When I went to think what the theme was, I thought, lyrically, the themes were home and heart, and I felt the one word that could sum that up would be Minnesota. That’s the one word, to me, where my heart is and where my home is, and it felt better for me to call it that than a record that was all about, literally, Minnesota. It just felt more like Minnesota to me for the variety of experiences I’ve had up here. It sort of symbolized it well.

RR: I lived in Minnesota for three years and it is difficult to explain its appeal to others unless you’ve spent time there.

MJ: Yeah, it’s true. It is a blend of really really amazing woods with the sophistication of the art scene. The public radio and the theatres up here are so good. It’s just such a clean place. The winters are intense, but what happens is that the place just gets so cleaned every year by the winters that the spring, the summer, and the fall are so vivid and fresh. There’s just nowhere like it.

RR: This seems to be a recurring theme with me lately, what with my own situation, as well, but how much of your family life impacts your ability to tour?

MJ: Yeah, definitely. I’ve definitely cut back on the touring a ton. When my kids were

really little, I toured a lot. My kids are 8 and 5 now, and as they get older, I will be home as much as possible, so the touring has shifted to where I’ll fly in and do a weekend here, and fly back home, and then, fly back out for another weekend. For this record, we’ll go to the East Coast and the West Coast, but I’ll make sure there’s a break between them, and I’m going to make sure there’s a couple of months between that and when I go down to the south and do a tour. I just try to make sure I break it up enough that I’m not missing any holidays or birthdays or anything like that.

RR: How do you reconcile that with the nature of the music industry these days? Let’s say you record an album that, in theory, should stand the test of time, and should be valued by many people, but the music industry is the way it is, so is it a situation where you fall into a trap where if you don’t tour, you cut back on your chances to be heard as an artist?

MJ: Yeah, for sure. The more the Internet becomes the massive medium for music, it’s like the touring becomes like…that’s what I have to do to make sure that people keep hearing about it. Touring becomes a way bigger part of my life than it did. I shouldn’t say bigger part, but more important part than it did, or has been before. I have to keep doing it, so I just have to keep figuring out a way to do it without compromising my family. I always look at it as my lifelong journey. I don’t feel as much pressure on it; I just make sure that I stay sane about it, take breaks, and I just want to make sure that every show I do is as good as it can be, so I make sure that I’m ready for it and properly rested.

RR: I liked what you said about every show being what it could be because I feel that way about Minnesota —every song is as good as it could be within this context. Let’s talk about the instrumentation on the album. The piano, obviously, plays a pretty large role. Also, there is spare instrumentation, overall, and the music is all wedded in a beautiful way to the lyrics. Was there a conscious choice to focus some of these pieces on the piano?

MJ: I think those are the songs that felt the strongest. There were a bunch of other songs on guitar, but when I’m writing, I hang out in my studio and I look around and see what kind of instrument looks like fun to me that day and that’s usually what I end up playing. I’ll sit down at the drums and write there, and I’ll grab a guitar, but for this record, I found myself at the piano a lot, and then at the end of the day when we had the batch of songs those really felt like the center of the record to me. It was sort of like after the fact, it felt like more of a piano record because I think all the songs I played on the piano ended up on the record.

RR: The center of a record. How do you determine the center? Is that a difficult process for you, and how do you translate that into the sequencing on the album?

MJ: I don’t know. It is more of a feeling. It’s a feeling like a completeness of a certain song. I can’t really put my finger on it. I can tell you for different records what it was. For

Blood of Man, when I had the song “The Field” and “Tourist,” and also wrote “Pittsburgh,” all of a sudden those three songs the record felt like it had its center, and I felt like I could go off from there. I remember with Century Spring, “Sorry Signs on Cash Machines” and “Killer’s Creek”—those were the center of the record, and everything went off from there. With Minnesota, I wrote “Raindrops on the Kitchen Floor” first and I felt “Wow, this song is a really different thing than anything I have ever written and I really like this song.” Once I started on the piano, then I wrote “Clutch” and I thought, “O.K. “Raindrops” and “Clutch” together have a piano theme,” and then I wrote “Bitter Heart,” and I thought, “there’s a real theme going,” and that is the emotional center of the record—to me, I don’t know, the feeling of it, they all kind of string together.

As far as sequencing, I try to make sure that at least that part of it is represented right away. If the casual listener only listened to the first two or three songs, they would definitely get the feeling off the whole record from the first couple songs. And then, I make sure I bookend it, the last song on the record bookends. On this record, the first song [“Bitter Heart”] and the last song [“No Relief”] both start and end with piano lines.

No Comments comments associated with this post