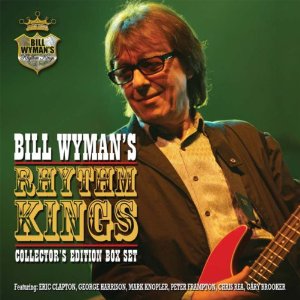

Since leaving the Rolling Stones nearly twenty years ago, bassist Bill Wyman, a founding member with three decades of service with the band, has kept himself quite busy. On November 22, the musician releases Collector’s Edition Box Set, a five-CD set of the first four Rhythm Kings albums recorded in a remarkable three-year period of time. The roots music band has been together for 13 years, and Wyman’s work leading the outfit has been admirably inspired and creatively sound—sifting through prior eras of ancient music like a gifted archeologist to find a fresh and vital way to craft new music.

Jambands.com sat down with the legendary original bassist from the Stones and current leader of the Kings during rehearsals for the latter outfit’s six week-plus tour. Wyman was also preparing for the debut exhibition in England of some of his photographic work. The man keeps moving forward—from archeology to books to photography to music, he has truly become quite the Renaissance man in the late stages of an impressive career, with no end in sight. At 75, Wyman is humorous and youthful with more than a fair share of tried-and-true wisdom thrown in for keen experiential measure. In the end, the artist has seen how life can work, occasionally and often unfair, but has managed to offer his own creative voice, threading his art with particularly memorable characteristics, without ever losing sight of his own individual trademark resonance.

RR: It’s unbelievable to me that so much material was recorded in such a brief period of time—1998-2001—on the new box set.

BW: Yeah, we do everything in take one, take two, take three. That’s it. If you can’t get it in three takes, out the window, and start on the next song. That’s the only way to capture the essence of the original. If you go through a Fats Waller song, or Ray Charles, or Chuck Berry, or whatever it is, you’ve got to capture the essence of the song that makes you like it. And the only way to do that is to get a recording of it with the band when everybody is having a good time, they’ve just got into it, and they’re just throwing things in. It works out for us that way; that’s the way we’ve done it right from the beginning.

RR: What is fascinating is how you went back to earlier eras when you were selecting material to record for these albums, but you found new ways to make music, even down to the way you play your bass on these tracks.

BW: Oh, you’re right. Yeah, I had to adapt my playing because over the years I’d gone from blues to R&B to rock and then to heavy rock, really, with the Stones in the big stadiums and everywhere, and I realized that I had to play in a different way because all the songs that we were doing with the Rhythm Kings were roots music, where the bass player was a double bass—all the Chess Records with Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Walter, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon—or, there was no bass at all on them, so I couldn’t play one bass and I had to throw away all my ideas from the past

(laughs) and start again, and think to myself: “How do I do this?” I used to sit down and think, “Well, double bass plays in a different way to a bass guitar.” They pull down from the high strings, usually, and with a bass guitar, you usually play it up from the bottom strings. If you play some boogie, you play [Wyman scats the three different variations of what a bass sounds on a traditional bass guitar], but on a double bass [Wyman scats the percussive sound of a double bass]—you know what I mean?

RR: Yeah.

BW: Pull down from the high strings downward. So I had to play more like that—the feel—and, also, soften my sound, which I did by playing with my thumb, instead of a pick, and doing it very, very lightly. [Author’s Note: Ironically, at this point of our conversation, one of Wyman’s daughters made a rather loud noise on an acoustic guitar.] Careful. So my daughter just smashed the acoustic guitar. (laughter) She just whacked it. She was trying to do it quietly while I’m on the phone. (laughs)

Yeah, I had to really rethink my way of playing, but still play also with an 18-inch speaker, which I’ve always done since the beginning because that gives me that fat bottom that sounds more like a double bass. And after a while, it did start to sound like a double bass on some things.

I’ve fooled a few people. I remember Jeff Beck saying to me once, after he’d done some of the Rhythm Kings because he loves our stuff, and he said, “So, who’s playing the bass on some of the numbers on the early albums?” I said, “I am.” He said, “No. No. No. It’s a double bass, and I know you can’t play a double bass because your hands are too small. You’ve told me that.” I said, “It’s not double bass; it’s me playing on the bass.” He said, “God, that fooled me; I thought it was a double bass on there.” (laughs) It does work once in a while, but you don’t get the slap, obviously, you know. [Wyman scats the bass slap] You can’t get that stuff, but you can get the bottom fatness and you can play like one, so that’s as good as I can do it.

RR: Who is that? That’s Bill Wyman.

BW: (laughs) There you go, yeah—you can fool some of the people some of the time.

RR: Your songwriting process evolved while working with the Rhythm Kings, too. You have formed an important collaborative duo with Terry Taylor over the years.

BW: Terry’s been a friend of mine since late ’69. He was in bands that I produced that toured America, and were quite successful in Europe, as well. Then, he was on all my solo albums, movie scores with me, and all that, so it was he and I that decided to create the Rhythm Kings. We decided to call ourselves the Dirt Boys. We were originally going to come out and do some old 30s blues music—just the two of us—and then, we decided to add a piano, and it might be nice with a drummer, and then (laughs), it became the

Rhythm Kings, instead of this Dirt Boys duo as we first thought.

Terry’s very important, but when I wanted to write songs, I decided to write them in the style of the songs we were covering, which were mostly from the 30s, 40s, and 50s. I realized that in those days people sang differently, horn sections played different lines, backing vocal harmonies were different, and so I decided to write songs with those things in mind, and, also, to use slang of the day, like “keep on truckin’” and all that kind of stuff that I’d heard off blues records and I’d heard off early jazz records of the 30s and 40s. I’d incorporated all that stuff, Terry and I write the music, and I do the lyrics. I write lyrics. I try to write lyrics in the same way, as I said, using the slang of the day. In the end, if it’s done right, and the band put it together in the right way, it sounds like its come from the 1930s, and that’s fooled a lot of people, as well, because people ask me, “Who did the original that you copied that from?” (laughter) And it’s kind of pleasant to fool people sometimes because it shows we are doing it right.

No Comments comments associated with this post