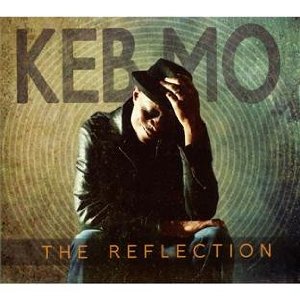

Keb Mo recently released The Reflection, a dozen track collection, and his first album since 2006’s Suitcase, which both confidentally and consistently showcases the singer/songwriter’s wide range of influences. The work also appears to consolidate the diverse strands of his music into a single powerful focal point: the man’s vision, itself. Mo is an astute songwriter, and he surrounds himself with like-minded individuals who share his work ethic in the studio and beyond to craft that unique “song to last a lifetime.”

Jambands.com spoke with Keb Mo after the release of the album, and during his tours in support of the sublime record out on the road. Mo and his band are in Europe in late October, before heading back to America for a late 2011 run. Mo is a warm, loose, and intelligent conversationalist who manages to put the listener at ease, not only on record, but in person, as well, with his friendly tales of songcraft, musicianship, and life lessons. Whereas others may count the calendar pages which have flown off the wall, Mo does not, seeking instead to live in the inspired moment, always active, always focused on that next piece of work, which will help define who he is as a man and an artist.

RR: I’ve been living with The Reflection for a while now, and I know you definitely have, as well. Did you want to talk about the production of the album?

KM: It was like diving into the deep blue unknown sea. (laughter) I got the songs together and started making the record. I wanted a certain quality and a certain consistency, and it was harder than I thought it was going to be to get. It took me a good while to get it. I kept listening to it, kept recording it, kept changing things until I got it to where I wanted it. It was a labor of love.

RR: Why was it so difficult? Was there a certain sound that you were looking for, and you wanted all the tracks to meet that high standard?

KM: I listen to all my records. Whenever I do a new record, I listen to all my records in a row. I listen to them and I try to fix everything that I thought was wrong with all my other records. (laughter)

RR: That’s a very interesting approach.

KM: “What am I doing wrong with this record? What am I doing that is resonating, and what am I doing that’s not resonating?” Keep the good. I just wanted a different feel. I didn’t want to compromise on it. And I had heard so many compromises on some of my other records that I just wasn’t comfortable with it. I wanted to make a record that I could sit down and listen to it and not switch.

RR: Did you decide fairly early on to self-produce the record?

KM: Yes. I produce my records because I’m the only one who has time. No one has enough time, and I don’t have enough money to pay [an outside producer] with as much time as I put into it. If I could, I would. (laughs) I have the time, and nobody else does. Nobody else cares as much as I do, so I figure I better do it myself.

RR: How much was it a collaborative process with your engineer, John Schirmer?

KM: It was a lot. There was a lot in the sounds and the mixes. I’m the music guy and he’s the mix guy. As far as getting the sounds and what mikes to use like on the vocals, the vocal tracks, we did this thing where we recorded a lot of vocals and we did it in my studio in L.A.. When we got here [Nashville] we had an old RCA, an old Norman mike, and it was really exotic gear to record it, and then, we got to L.A. and recorded on a mike that they make here in Nashville called Miketek, one of these API lunch box series, and it just sounded killer, so we did all the vocals over again with this new mike. Sometimes, I used drum programs, which I hadn’t used on any records before, so that was new. “What? You’re using drum programs?” “Yep.”

RR: You offered many different sounds within the unified framework, but you also brought in a lot of guests who enhanced, rather than detracted, from the piece.

KM: I guess the thing I’m most proud of was that we got a nod from some bass web site that we had the “Who’s Who of Bass Players” on The Reflection. That was really cool. I used great drummers, John Robinson, Gordon Campbell, and my son is on one track. The initial tracking sessions included a group of musicians. They tracked on all the records, but as time went on, and I started to scrutinize the tracks really closely, I found that I didn’t like the way everything gelled. When you go into the studio and you cut tracks, like a three-hour session and you cut two tracks, sometimes you are in too big of a hurry, and you pay for it later. It’s also hard to get isolated and get everybody really locked in to what you want to do; it takes a little time. I was really persnickety, so I ended up redoing a lot of things, fixing things, and just really, yeah, there was major surgery on that record. Major. To do all that and maintain the feel and maintain the honesty was really difficult.

RR: Some musicians are rushing to capture that feel because they think they are going to lose the moment.

KM: Yeah, they think that, and I always tell them, “Look, you’re you; you’re never going to lose the moment. You’re you. You can’t lose it. I don’t care how many takes you do, you can’t lose it. It’s always there.” Some of them just don’t have the emotional stamina. And, also, they want to get out and they want to go. They want to know that they’ve done a good job and leave. Some will stay all day; some will be different. People are different. I stay until the party is done. I stay. I’m in, man. Even at somebody else’s session, I’ll sit there and stay. Sometimes, they’re like, “No, it’s good; go ahead and go,” and I hear the record later and I think, “Oh, man, you guys should have stayed longer.” (laughs)

RR: I love that. You have a lot to teach modern day artists because, even with all that work, the record sounds effortless, and I am aware of that challenge.

KM: Yeah, and it sure wasn’t. (laughs)

RR: After all that, what was your sense of the record?

KM: I felt really good. I felt really good about it. Yeah. I really did. And that’s a scary feeling. (laughs)

RR: Why?

KM: I felt really good when it was mastered and done, and then afterwards, I didn’t listen to it for about two months after it came out. I couldn’t listen to it. I was scared. I had spent some much time with it—wow, I was immersed—so I was just scared because if it sucked, I was going to have to kill myself. (laughter) It would have been two years down the drain. It was like, wow, it was a real mind fuck in terms of how I worked so hard on it.

No Comments comments associated with this post