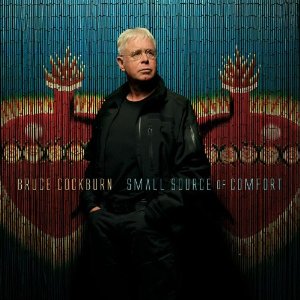

It’s not surprising to find Canadian singer, songwriter and humanitarian Bruce Cockburn calling from San Francisco. The West Coast has become a second home due to lengthy stays to be with his girlfriend. Not fond of air travel, he’s driven there multiple times, and previously to her former residence in Brooklyn. The meditative abilities brought on by the open road have become a significant source of inspiration. The miles spent on North American highways enabled him to write the material for his current album, Small Source of Comfort.

As he describes in the liner notes, he “had a vision of music, electric and noisy, with gongs and jackhammer and fiercely distorted guitars.” Instead, the solitude of driving plus the discovery of violinist Jenny Scheinman led to an intimate and introspective set of acoustic tunes that blend folk, blues, jazz and rock. Despite the lack of volume, the songs maintain a significant intellectual and emotional impact that’s customary for Cockburn, who has mixed personal and social politics over 31 studio albums. Relying on a sense of movement that mimics their creation, the songs become reflections that pass by like mile markers. Later, those interior musings branch out and acknowledge the fragility of existence when he recounts a Ramp Ceremony held for a fallen soldier in Kandahar, Afghanistan during “Each One Lost.” Still, it’s not all drama and darkness. A perverse sense of humor pops up where least expected. Besides the occasional lines, there is the scenario of “Call Me Rose,” where he imagines Richard Nixon reincarnated as a single mother with two children living in a housing project.

My conversation with Cockburn can’t help but mix music, politics, war and social change because that’s the landscape where his four decades as a solo artist resides.

JPG: With the Occupy Movement gaining steam but also attracting enemies, and your lengthy background with humanitarian efforts, I’m curious…how does one stay positive?

BC: (laughs) Umm…I think your ability to be positive depends on what you think the bottom line is in a way, and to some extent on your experiences, too, obviously. If you meet impressive people and get energized and feel like things can move in a positive direction because of those people then, of course, you’re going to have a more generally positive feeling about everything. And the opposite is also true. For me I don’t think about it much. I guess, I feel generally hopeful in my life but when I look around I can’t find a logical excuse for that. (slight laugh) So, it comes down to what’s in my heart, and I suppose no matter what happens to humanity the planet will continue, the universe will continue. If there’s a master plan for it all that will continue. We will have been, perhaps, disruptive of it for a moment or two but I don’t like to look at it that way. I feel like we have to promote the best in ourselves and hang on to that as a source of energy to, if not fix things, at least keep them from getting so bad that we can’t stand it, that we can’t survive it.

*JPG: It correlates for me to the title of your album, Small Source of Comfort. Finding something to hold on to, savor the little victories. *

BC: Yes. That’s okay to take it that way. When I gave the album that title, it’s a line from a song (“Five Fifty-One”). I just felt that the phrase itself made an effective title. I wasn’t thinking too much about what I was promoting by calling it that. In the song, of course, it’s a bit ironic because a small source of comfort, the sun came up. Okay. (laughs) This is the best that we can do. And some days it is the best that you can do. You’re not dead and neither is the world, but, other days, of course, things feel better.

I’m not offering myself as a small source of comfort although people have come back at me with that notion. I think looking at love and looking at beauty and looking at all these things that are still strong in us and in the world, regardless of the trouble we’re in, it’s easier to operate and easier to feel like you’re moving forward and, maybe, genuinely move forward. So, if the album points at anything to do with comfort it’s that.

*JPG: When you mention that it’s meant to be ironic – the idea that the sun coming up being a small source of comfort – but there are lines throughout the album that offer brief moments of humor. Even “Lois on the Autobahn” in its own way because the actual road has cars rushing by at 100-120 miles per hour, or whatever it translates to in meters, but the song sounds like a light little ditty, a relaxing drive in the country. *

BC: (laughs as I struggle to translate miles into meters) I’m old enough to be a veteran of miles. It is kind of humorous. Like instrumental pieces, they’re not about anything. They’re just a collection of notes that, hopefully, makes some sense and starts somewhere and goes somewhere and makes you feel something. But you have to give them titles. In that case everybody who heard it said, ‘Oh, it reminds me of being on the road or driving’, certainly not in the 120 mile-an-hour autobahn but just of being on the highway. My mom died that summer and it just seemed like she would appreciate being put on the autobahn. I don’t think she would have been happy with the 120 miles-an-hour thing but it just seemed like her moving on, her sailing on to wherever she goes next. It’s a light-hearted look at death. (laughs)

JPG: But the humor is a bit surprising because, overall, you’re viewed as a serious artist. A lot of people may even view you as angry. ‘He’s that guy who’s gonna use his rocket launcher once he gets one…’

BC: Yeah, I would have preferred a smiling picture [one CD cover], actually, but we didn’t have one that had the same graphic power that that had. So, we decided to use that. Sorry to interrupt you there.

JPG: No, that’s fine. That’s the way of a conversation. Is there a certain responsibility you have by being Bruce Cockburn, where you can’t be stinking drunk in public or you can’t walk out of a McDonald’s?

BC: I’ve done both of those things, certainly often, actually, over the years. Often may be overstating it but it’s not an uncommon thing on the highway. When you’re driving, sometimes McDonald’s is the only option. It’s not my preference, that’s for sure. There’s a certain responsibility I feel to be truthful in my art and be as good at it as I can be but I don’t feel that I have a responsibility beyond that to my audience particularly. I guess, if the art was completely inconsistent with how I lived there would be something wrong. It wouldn’t be truthful. Having said that, I like to drink wine. I like to laugh. Occasionally, even force myself to dance. I do all kinds of silly things.

People tend to take things seriously. It’s one thing to take your art seriously or your work, whatever it happens to be. I think it’s appropriate to do that and be as good as you can be at whatever you’re doing. But sometimes, people forget that we all have the capacity to party a bit and we all have the need to let off steam and you can’t be serious all the time or you crumble. A great illustration of that came back in the early ‘80s when I first started to travel, when I first went to Nicaragua, for instance, and all the people I knew that were involved in solidarity work with Central America were terribly serious and terribly official and everything was heavy duty. You get down there and people are in a friggin’ war for their survival and they’re partying at every opportunity, dancing and laughing. You think, ‘Oh yeah. Right.’ There’s a perspective here that we found. The perspective in that case was that the people who were really in it cherish every opportunity to celebrate life because it may end. And, of course, we’re all in that boat. Most of us can ignore it most of the time. But if you live in Iraq or if you live in Afghanistan or…Afghans are not famous for their partying, I guess, but Baghdad used to be famous as a party town before Bush invaded it. The capacity is there. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that at all. I think it’s totally healthy. If all you do is party there’s a problem there, too. But if you party instead of looking at reality, well, that’s a problem. You need to loosen up from time to time for your own survival.

JPG: That reminds me of friends of mine who were getting their masters degrees and wrote their papers on the Holocaust. Due to all the really depressing and shocking research that was involved their advisor recommended that in order to get their minds off the subject they should pay attention to something totally mindless…which is how they became fans of wrestling and NASCAR.

BC: (laughs) I totally get that, especially about NASCAR. (laughs) But it’s exciting — things that roar and go fast. That is exciting. I totally get it. The Holocaust is not…every time we learn something new about it it gets worse, and you think what you knew about it 30 years ago seemed to be as bad as it ever needed to get, but as more information surfaces, and people doing research like that, it gets worse and worse. Then, of course, you look around and you can find people doing a less scientific version of the same thing, where possible, today in the world and…you have to be able to step away from that.

JPG: You mentioned Afghanistan earlier. Are you familiar with the books Fire and War by Sebastian Junger.

BC: I know the name but I haven’t read his books.

JPG: The reason I bring it up is I recently finished Fire, which is a collection of his magazine articles with much of it finding him at one war-torn area after another. And it was interesting that in the later chapters he touched on the situation in Afghanistan as far as the political climate after the Soviets left and how the Taliban filled a void and took power in the area before 9/11.

BC: Which they’re going to do again. Talking about depressing outcomes. There’s a few good books on Afghanistan. I can’t remember the names of the authors but there’s a Canadian journalist who spent a lot of time with the Mujahedeen when they were fighting the Russians, who are essentially the same people, and he wrote a book called “War at the Top of the World.” He writes for one of the Toronto papers. It’s a powerful book about his experiences and his take on what it is we, quote unquote, are fighting.

It’s a tricky thing. From a military point of view if you’re gonna get into a war like that you’ve gotta be like the Romans. You’ve gotta be totally ruthless. You’ve gotta be so bad that you win. And as bad as we can be, we’ll never let ourselves be that bad. Thank God. The Romans went to war against Carthage. Okay, after three wars with them, they finally decided they had enough and they just exterminated the population, sold the survivors into slavery and bulldozed the city, basically plowed it under. There was absolutely nothing left. And if we want to beat someone like the Taliban and get them out of the world, that’s the way to do it but we’re not going to do that and I’m not suggesting we should. But if you’re not going to do that, don’t expect to win the war. You’ve gotta find some other way to get the job done than just beating them up. There was a U.S. Senator whose name I forget because I never quite noticed it who a couple years ago proposed the idea that we should buy the Afghan farmers’ opium at a rate higher than the Taliban are able to pay. And let them be the supply to the world because they’re growing it anyway. We need it. There’s a use for it, and let it be legitimate. That would take at least that aspect of the financing right out of the Taliban’s sack of resources and give those farmers a profitable thing to do, etc, etc. It just seemed like a really good idea, but there was a lobby against it by whoever controls the current supply of opium, the legitimate supply.

No Comments comments associated with this post