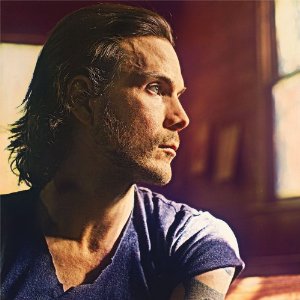

Though his family band The Felice Brothers originally earned a reputation for partying that rivaled their ability to write deep, honest, folk songs, Simone Felice has always been a sensitive soul. A far cry from his days as a self-described “lonely” child spending his free time at the library, he’s also grown into something of a lynchpin connecting The Felice Brothers with The Avett Brothers, Mumford & Sons, Dawes, Old Crowe Medicine Show, and the many other increasingly popular bands that blur the lines between classic Americana and modern rock. As the oldest of three Felice Brothers, Simone first rose to prominence playing drums and helping out on the songwriting front in his family band, but after his girlfriend suffered a miscarriage in 2009, he struck out on his own. Writing through his grief, he used his first batch of songs to ignite the equally honest, Huck Finn-inspired folk-rock band Duke & the King with George Clinton collaborator Robert “Chicken” Burke—and completed a critically acclaimed full-length novel. After he suffered another health scare—Felice had an aneurysm as a child that left him clinically dead for moments—the multi-instrumentalist looked even deeper inside and started work on his first full-length solo album. Shortly after the release of self-titled Simone Felice, the Woodstock, NY-based singer, songwriter, author and multi-instrumentalist discussed the emotional circumstances that spurred his solo career.

When we spoke last, you mentioned that you wrote the music on your recent solo album while you were going through two very emotional situations: your wife was pregnant but you were also facing some serious health scares. Can you start by giving us a little background about what was going on at the time you started working on Simone Felice ?

Well, in early June 2010 I was overseas in the middle of a little solo tour. I collapsed while walking up seven flights of stairs in a hotel and crashed in the hallway. When I woke up I kind of crawled to my room and I called my mom—it was my instinctual move to call my mom. I told her, “I think there is something wrong with my heart”— I knew inside there was something wrong. I never go to the doctor, and I don’t have insurance—I just go with the flow and am bad about that. I was born with this congenial heart defect, so I flew home the next day after my last show and they drove me to an Albany, NY medical center. The doctors all piled in the room and looked at my heart on the screen. The doctors kind of whispered to each other and said, “Mr. Felice, there is no medical reason for why you are still alive—we need to get you into heart surgery tomorrow. The aortic valve in your heart is closed up, and it is a wonder you didn’t die in the airplane or on stage.”

So I just had to give my body over to the great, big Indian in the sky and they wheeled me away. They dropped me under the knife—I had to say goodbye to my wife and her eight-month pregnant belly, and I didn’t know if I was ever going to see our first child. I survived—thank the gods of wind and weather and rock and roll. I was supposed to be in the hospital recovering for a month but I had the great fortune to have a cousin who was a nurse at the Albany Medical Center and she sort of broke me out of the recovery room two days after the surgery so I could recover at home in the mountains with the fresh air. I don’t know about anyone else, but the hospital the last place you want to be when you are recovering.

So luckily I got to heal up at home and, as Neil Young says, I was helpless, helpless, helpless. I couldn’t take care of myself or lift anything for about a month. I was on heavy doses of morphine—they were giving me these waking nightmares, weird visions and dreams. I wrote it all down and a lot of those ideas and nightmares became the songs on this album. And also the joyful songs inspired by my daughter Peal being born. She was born a month after the surgery, and I was just strong enough to pick her up. We had her at home in the mountains with a midwife, and I was just strong enough to pick her up out of the water. It was the most magical and transcendental moment of my life. I was given a new chance at life with basically a new heart and then was able to witness once of the most beautiful beings coming into the world. I cut the cord and looked her in the eye and knew she came from a better world than this. She is here to teach me. So this album is the culmination of those nightmares and those beautiful redemptive visions as well.

After going through such an emotion time, did you feel more confident about releasing an album under your own name instead of with The Duke & the King or your brothers?

Honestly Michael, I have been so privileged to be a writer, a player, part of some special records with my brothers—I was on the Avett Brothers’ record I have gotten to be a part of these great bands’ albums. But after the surgery there was something in my head

There’s always been a whispering on what to do—what path to take artistically and spiritually. Something really told me it’s time to tell my own story. My brothers have given their full blessing and been behind me all the way. We did about three or four songs together for my new album—they have a studio at an abandoned high school in Beacon, New York that is amazing. We got to record there in the round all live—it was the original configuration of the band with me on the drums.

Where did you record the rest of the album?

We recorded a lot of it in my barn—it was really naked and lonely, right after I could start to sing again. The first thing I did was set up the mic and try to catch the purity of the moment of the songs that were coming out. And then I did two songs with my friend Ben Lovett from Mumford & Sons. We recorded “Give Me All You Got” in my barn in Woodstock—he was up here with me for a couple of weeks. And then he invited me to a space he works at in London last spring. When I got there it was such a treat because—though I didn’t know until I got there—it was where The Traveling Wilburys made their records. The first tape I ever got was a Traveling Wilburys album—my father bought me in Leeds, so those records are kinda magical to me.

We worked in this old little church in the south end of London, alongside the ghosts of Roy Orbison and George Harrison. It was a really special place, and we recorded the song “You and I Belong” there. Ted Dwane came by to play a little and our friend Hillbilly Harry came to play some banjo on a song I wrote the day after Pearl was born. It’s a song about living in the moment, each morning. I wrote it really lonely and naked, but we kinda turned it into a hillbilly dance party—a celebration of life. I’m really happy about the way it came out.

No Comments comments associated with this post