After listening to guitarist Jimmy Herring’s new solo album Subject To Change Without Notice it would be easy to say that the man is on top of his game – but it wouldn’t be accurate.

The fact is, Herring’s already-amazing game keeps getting better.

The 50-year-old guitarist (who hangs his hat in Georgia when he’s not out on the road with Widespread Panic or his own Jimmy Herring Band) may be an idol to pickers all over the world, but in his mind, he still has a lot to learn. And he still wants to learn.

In transcribing my conversation with Jimmy on the eve of his tour behind the release of Subject To Change Without Notice, I was tempted to edit out some of our diversions into guitar talk. But in re-reading his words, I decided they had as much to do with passion and love for his craft as they did guitar neck radiuses and chord progressions. Trust me: you won’t have to be a picker yourself to enjoy Jimmy’s thoughts about friends, family, bilgewater … and the mantra of “Just show up.”

BR: Jimmy, I promise I’ll do my best to stay on top here and not get talking about guitars too much – because I could seriously derail this interview.

JH: (laughs) Oh, me too, man – me too. (laughter)

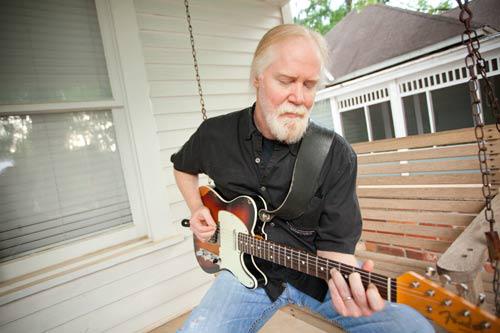

But I am going to ask you about that sweet-looking Tele you’re holding on the back cover of the new album. What’s the story with that guitar?

That’s just a Fender reissue that I found, but it felt really good. Somebody had cut into the body to put a humbucker neck pickup in it and they didn’t do a good job, you know? So the guitar had a nasty, ugly, chewed-up part of the body underneath the pickup – but I don’t care about that stuff. I got the neck refretted – I like super big frets and flatter necks than the way Fender usually builds their guitars.

That’s the sort of a thing that’s been going on for years among players – get a guitar that you like and flatten the neck out quite a bit so it plays a lot better. It’s not a secret. I fought normal Fenders for years without fret jobs or flattening the neck and I’d see people like Steve Morse or Stevie Ray Vaughan play and I’d be, like, “How come I can’t do that? How do they do it so easily?” And then I found out about the flatter neck and big frets – it made a huge difference.

So anyway, yeah – I love that Tele. I used it on a bunch of stuff on the album.

When I wrote about your solo album Lifeboat in 2008, I described it as a very personal album – you were dealing with some loss in your life at the time. How would you compare Subject To Change Without Notice to Lifeboat ?

You know, you’re right that I was dealing with some stuff on Lifeboat – although some of it had happened years earlier … like the loss of my father. Sometimes I’m not the greatest at dealing with those sort of things, so I have to put it aside or it’ll just kind of consume me … and the music helped me release some of that.

Another thing about Lifeboat was I was really determined not to have a guitar record; it was important to me that the music come first and not the instrument that I happened to play. And I felt really strongly about getting a lot of other instruments on there so that the solo time was shared equally … like say, Kofi Burbridge on the flute or Gregg Osby on the sax or Matt Slocum on the keys. It was important to me to have the music first.

Plus, I was really into the trance thing on that record. There’s a lot of minor 6 chord-oriented stuff, like “Jungle Book” or “Grey Day” – those tunes were centered around a minor 6 chord. I’d really just discovered it and the minor scale that goes with it just kind of puts me in a trance … I wanted to explore that. Those were the things that Lifeboat was going for.

With this album, I really just came around to wanting to play some simpler music – bigger melodies and not really worried about whether it was perceived as “guitar music” or not, you know? I mean, if it is, that’s fine, but what I really wanted to do was play some simpler melodies and simpler songs. There are a couple jazz fusion-type things on the album, but a lot of it singer/songwriter-type songs – except there’s no singer. (laughter)

The guitar is the voice. Or the keys, or the sax.

Right, right.

Speaking of sax, one of the things I noticed on this album is how much more horn-like your playing is – not just in terms of tone, but in the phrasing and the way you’re offering the ideas. That seems like something that’s developed over the years.

Well thank you, man – thank you so much. That’s been a conscious effort for a big part of my life. Back when I was in Bruce Hampton’s band, there was a lot of ridicule – it was tongue-in-cheek; it was all in fun – but Bruce would give me a lot of crap about the guitar being more important than the music. (laughs)

Bruce knew the kind of people I liked to listen to and he was teasing me, mostly … he just wanted me to think about it, you know? Think about where your influences are coming from. Don’t just listen to other guitar players; listen to all music – listen to music that doesn’t even have guitar in it. And as a result of that, I ended up going through a long period of time not listening to any other guitar players – but listening to a lot of horn players. I think that had something to do with what you’re talking about.

What I hear – and I’m probably over-simplifying it, but it’s what I hear – your guitar takes breaths.

Oh, man … (laughs) Thank you for noticing!

Is it a conscious thing while you’re playing?

Thank you so much, man … it’s one of those things that I really didn’t know if people were going to notice or not. Yes, it’s a conscious effort; like I said, I listened to a lot of horn players – and singers, too. The latest influence on me has been singers.

It seems like where I’m headed right now is to have a vocalist-type of quality. Especially in instrumental music where you don’t have a singer – something needs to be there. Plus, the human voice is the most splendid instrument of all.

Derek Trucks is a profound influence on me in that way. He can sound as much like a singer as any instrumentalist I’ve heard. The idea of playing in phrases is something I’ve been trying to develop for a long time. Horn players have to take a breath, you know? But guitar players don’t … they don’t need it to produce a note, while horn players and vocalists do. So horn players just naturally play phrases – and where you leave spaces really defines your style. You hear that cliché all the time about “what you don’t play is just as important as what you do play” … and I’m trying to implement that. I think it’s important.

To the point where I’ll hear the same thing a horn player might do when they have that last little blast of air left and they’ll let fly with a flurry of notes …

Yeah! Yeah! (laughter)

You produced Lifeboat yourself; this time around you had John Keane as a producer. How much did it change things having him there?

Oh, John is brilliant, man. Yeah, I produced Lifeboat, but I also had an engineer there who knew what he was doing. Real producers to me are also engineers – and I’m not an engineer. (laughs)

John worked with me and let me make myself happy on a number of issues. Some producers, you know, don’t let you make yourself happy – you just play and they’ll say, “Okay, that’s it – we’ve got it.” Even if you don’t really like it, that’s it.

I told John, “The reason I want to work with you is you’re brilliant and you know how to get these amazing sounds. You’re the fastest engineer I’ve ever seen in my life and I’ve worked with a lot of really good engineers.

Plus, John has a million great musical ideas. If I hit a wall, and I’m trying to come up with a melody, John can help me with that because he’s a musician himself. He just has a great idea of what a song should be.

John may not have written any of the music, but he had a profound influence on this record. I would not have wanted to make this record without him … he was an integral part in every way.

No Comments comments associated with this post