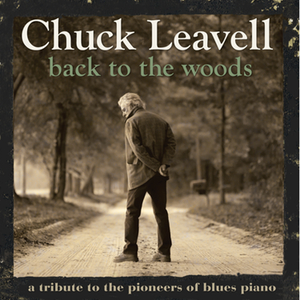

Keyboardist Chuck Leavell has worn many hats since he entered the music industry over 40 years ago: The Allman Brothers Band’s soloist after Duane Allman’s death, leader of the seminal fusion project Sea Level, Rolling Stones musical director, sideman to stars like Eric Clapton, author, tree farmer and solo artist. Despite is eclectic resume, Leavell’s latest solo album is still a left turn, the blues-piano tribute Back to the Woods. A collaboration with his son-in-law, the project finds Leavell tracing the history of boogie piano and shedding some new light on his own influences.

While rehearing with John Mayer for an upcoming project, Leavell discussed his new album with Relix and Jambands.com. He also discussed his new band Watson’s Riddle, his recent Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and even The Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary rehearsals.

Let’s start by talking about your new blues-piano tribute, Back to the Woods. What inspired you to do an album of blues songs at this point in your career?

CL: First of all, it came about because of my son-in-law, whose name is Steve Bransford. He was the co-producer on the project. Steve has an interesting story, and he’s just a wonderful person. Steve is a Ph.D. graduate from Emory University in Atlanta, and his discipline is in American History with a slant on visual arts and roots music. So Steve came to me and said, “I got this idea, it may not have any value, but there’s been all these tributes in the past to blues guitar players and singers and songwriters, and people think so much when they think blues.” When you think of the blues, the guitar is the first thing most people think of. But he said, “You know, there’s not been anything done for these obscure blues piano players, and I think you’re the guy to do it.” And I thought it was an interesting project because a lot of these artists are very little known.

When you look at LeRoy Carr, Skip James and Little Brother Montgomery, they were certainly precursors to players like Otis Spann and Ray Charles, both of whom we cover on the album. That was the latest phase of blues that we get into on the project. But then, even going forward from that, players like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis were influenced by these blues piano players as well as gospel. But these artists that we covered are very important figures and it’s wonderful that we have these early recordings. So that was the impetus of the project: to bring to light these sort of mostly unknown names to people and to, of course, not to try to emulate what they did in their recordings but rather interpret it and show in the process how they influenced my playing in particular.

When it came to choosing the songs, were these mostly songs that you and Steve already knew when you started? Or did you spend time researching some lesser-known musicians together?

CL: Well, first of all, my son in law Steve had done a lot of research. He gave me about three CDs of well over 100 songs—it was probably 120 or so songs. A lot of it I was familiar with—I am familiar with LeRoy Carr in particular. Montgomery I knew some about, but had not really dived into his catalogue as such. And, so there were definitely artists that I had never heard of. The most obscure would probably be Leola Manning, for whom—I think we say it in the liner notes—that’s maybe the only recording she did. And then Jesse James would be another one I was totally unfamiliar with. That may be the only known recording that he ever did as well. Skip James is known more as a guitar player, and it’s interesting to me, I didn’t know he played piano until Steve brought it to light. So I found that interesting and I think he has a really neat technique, a real syncopated technique on the piano. It was my idea to do the Otis Spann and the Ray Charles. I mean, Ray has been my musical hero all my life just about, and I certainly wanted to celebrate him. I think it was really fun to find that early track from ’53, “Losing Hand,” something that I would imagine 95% of people who know about Ray Charles have never heard that track. And then there is Otis Spann, one of my heroes from the Chicago-style blues playing. I thought it was important to include them even though we focused 85% on the pre-war era which I think is a very interesting era to focus on. As you can tell, we leaned heavily on Leroy Carr. I think there’s five tracks of his, and we thought about that, we said “Geez, we’re doing so much of him,” but at the end we said it really doesn’t matter because the songs and the process are so good.

Let me just explain to you the process. Steve gave me the CDs, and in my other life, as you know, I’m a tree farmer and we live in the country in Georgia. So, for about three months I rode around in my pickup truck working on my place listening to this music and absorbing it. Again, a lot of it I knew about and a lot of it I didn’t, so I just listened and listened and slowly began to pull out the songs that were speaking to me, the ones that I thought I could interpret and I would enjoy playing. I want to do things that turn me on. Slowly the process began and then, I’d finally get to the piano and start learning these songs and going through and playing them and finally cutting it down to probably 25-30 songs and then from there to the 15 that we recorded. Getting back to the Leroy Carr thing, when we finished it all there were so many [of his] songs on there but I said, “It doesn’t matter because I enjoy playing each and every one of them, so let’s not worry about it. Let’s put everything that we finished and recorded on the record.”

You have a range of musicians on Back to the Woods, including Keith Richards and John Mayer. At what point did you put together the album’s core band?

CL: First of all, I wanted to stay fairly close to home in the recording process, and I didn’t want to do it all at once. I didn’t want to go in with 15 tracks and try to record it all in 2-3 days. I wanted to do it in segments because I had some other things going on in my life: the work on my tree farm, and my work with the Mother Nature Network, which is largely part of who I am. I wanted to spread this out and do it in segments that were comfortable to me time-wise. So my friend Jim Hawkins, who was an engineer in the Capricorn Records day in Macon, Georgia, and who actually built one of the early versions of the Capricorn Studios, had built a studio of his own in Athens.

Athens is only less than a two hour drive from where I live, and I thought well that’s good, it gets me out of the house, it gives me somewhere different to go, Jim’s a good friend, he has a nice facility and a nice piano. So that made sense. And then I said well, if I’m going to record in Athens, what players might be up there? The bass player is a guy that I had worked with in the past on some live gigs. A friend, Randall Bramblett, recommended him to me and, as I’m sure you can see by the liner notes, his name is Chris Enghauser. The other thing about Chris is that he’s a really good upright player, and I wanted all upright on this because that’s what was on the original recordings for the most part. So Chris was available and I was very pleased about that and we started thinking about drummers, and it was actually Steve that suggested Louis [Romanos]. Lou is somewhat of a Katrina refugee: he had been living in New Orleans for a long time and, when Katrina came, that obviously pushed him out of New Orleans, and he settled in Athens. So I had heard about him through Steve. I liked the idea that he had the New Orleans influence, so that was the core band.

Now, we also wanted Danny Barnes on the project. I’ve been a Danny Barnes fan for a long time. I’ve listened to all his records even going back to the Bad Livers stuff. I just find him to be a fascinating character. We brought him in for some of the sessions, some of the stuff we recorded as a trio, and it remained that way. We timed it so that he had some shows that were in Georgia and we grabbed him during that period of time and arranged a couple of days with Danny. Also, Randall plays on a few tracks and does so beautifully, especially the sax solo on the duet that I do with Candi Staton. A guitarist named Davis Crosby also plays on a couple of tracks.

Some of the things we recorded as a trio and then added extra parts. For example, the stuff that John Mayer and Keith Richards played on: we took the tape—or the files—up to New York to get them in Electric Lady. I’ve been working with John for about a year and a half now so I asked him if he would play on the record and he said, “Absolutely.” So we’ve got Keith and John at the same time.

So that was the process, and it was a very enjoyable process. With the whole thing stretched out, I’d say we maybe had five sessions over a six or seven month period. It was very casual, very slow and methodical, but I would say we probably spent eight, ten days in the studio working on the thing.

No Comments comments associated with this post