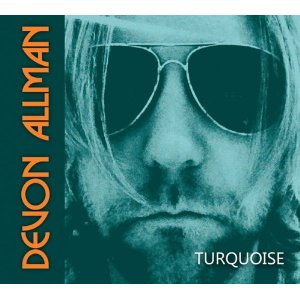

Devon Allman has been riding a wave of success with Royal Southern Brotherhood, a band that debuted last year with their self-titled studio album, which has subsequently produced a flurry of worldwide touring and attention. That recent accomplishment has allowed the guitarist/singer/composer to finally create a solo album, featuring an eclectic mix of rock, blues, soul, and a whole lot of charm and heart. Essentially, after over a decade of work as an artist trying to define his own path outside the shadow of his famous father, Gregg Allman, the man has suddenly found himself straddling two artistic paths, which both provide the outlet to explore his own talented voice. Turquoise, the debut solo album, created during a rare-Royal tour break, is an excellent 11-track work, consolidating the musician’s artistic strengths, while managing to sustain a consistent theme of purpose, creativity, and soul-searching throughout its entire sonic journey.

Jambands.com sat down with Allman to discuss his recent success with the Royal Southern Brotherhood, and the story behind the debut solo album, too, which also features his RSB bandmate Yonrico Scott on drums and percussion, and Myles Weeks on upright and electric bass. Allman is an intelligent and perceptive conversationalist, with a refreshing and mature outlook, that helps engage the listener on several levels, something that can be said about his recent work, as well, which, along with the decade-plus odyssey of his band, Honeytribe, help define a unique artistic vision—famous son, or not.

RR: I was pleasantly surprised with your debut solo album, Turquoise. Not that I was surprised that you could pull it off, but that there doesn’t appear to be a weak track at all. It is a very consistent work with a lot of heart and variety and some fairly moving material, as well.

DA: I can’t thank you enough. That’s music to my ears because when you’re in there making a record, you’re so close to it that you don’t know. There might be some things that are moving you, but you don’t know how it’s going to be taken, so I appreciate that.

RR: Besides the fact that it’s your solo debut, is it your most personal work to date?

DA: I think it’s always been part of me to open up, but I would say that, yeah, it’s pretty to-the-point and transparent and you know what’s making me happy or making me sad, so, yeah, I think it’s definitely my most personal work.

RR: Why do you think, at this particular time, you were able to create this album?

DA: I don’t know. This wasn’t something that was planned out. It wasn’t like, “oh, it’s time to make my most personal thing.” I think that I’m at a point in my life where a lot of the goals that I had initially set for myself, in terms of personal and business and career, I had hit, so it was kind of like a big breath of fresh air: I know who I am; now, I am ready for the whole next set of goals. There’s a lot of different vibes going on in there from celebration to melancholy. The one thing that really hit me was this blues theme of home that runs through the record. At the beginning of the record, I’m young and ready to run out the door—“get me out of home.” And then, by the middle of the record (laughs), I’m saying, “I wanna come home; that’s the only thing I want more than anything in the world.” So, just like anything, I think we’re all a product of our years and our experiences and our decisions. I’m just at a real good place.

RR: You mention the passage of time in a few lyrics, and it also plays a part in the continual theme of the entire album. Did you think about that when you were sitting down and going through the construction of Turquoise?

DA: I did not, actually, so it’s funny how some very basic elements of our lives like our home, or our home base, and time, our currency of life, end up being the strongest themes on the record. I think that that makes sense—those are common denominators for anyone to relate to, so, yeah, man, it’s a real life record, I guess.

RR: You’ve worked with groups in the past, and with one that has recently exploded onto our scene, so when did you decide you wanted to create a solo album?

DA: I think having been under a good bit of healthy pressure to come to the table with my best songwriting to be included for the Royal Southern Brotherhood record made me really dig and go, “O.K., I want my songs to stack up next to Cyril Neville’s without there being any kind of dip in heart or quality. That means I have to bring the most pure version of myself and my stories that I can to the table.” I felt like I did that with “Left My Heart in Memphis” and “Nowhere to Hide” that I brought to the Royal record, which I completely wrote myself. They weren’t co-writes. As soon as I heard the playback on those, it gave me the confidence to think, “You’re not just an aggressive blues jamband. You’re a writer, too, and you really ought to just take your next turn, and turn down the writing path, and really put your best foot forward in writing songs.”

Clapton did that in a certain juncture in his career, and I’ve really started to want to mirror, not the stylistic, but the career moves that somebody like Clapton took. Obviously, he’s an amazing, world-class player, but he has these amazing records in his discography. I just decided right then and there. I had the confidence—these personal or laidback songs of mine? They need to be magnified into a whole album.

RR: Confidence is the key word, and you mentioned that Royal may have provoked you into that feeling in a very positive way, which also circles back to what I felt about the solo album—there is confidence on the songs; you are telling a story in an unrushed, patient manner, and it sounds like a record you want to spend time with. How much confidence did you also gain from touring with the members of RSB?

DA: Well, any time you shake up your house, you’re going to have new perspective and you’re going to see other people’s takes on approach and touch and things of that nature. When I went from being a quarterback for twelve years to being an equal member of a team, it definitely makes you look over your shoulder at your brother and say, “Oh, that’s cool; that’s a nice approach.” And that can be from anything from a tempo thing to a feel to a touch to a groove. I think we’ve all effected each other in a very positive way.

But the confidence thing is, I don’t know, you play in the sandbox for ten years, and then somebody says, “Oh, we think you’re good enough to jump onto the beach,” and you do it and nobody’s kicked you off yet—this is good. (laughs). There’s a bit of, for sure, validation there. “All right, this is a side of me that I need to start believing in; it exists.”

RR: Let’s discuss two areas: the genesis of the solo album and the importance of Jim Gaines in the production of Turquoise.

DA: Sure. I’ll touch on Jim Gaines first. I was a fan of Jim Gaines for the last 20 years. I’m a record geek. I know what Jim Gaines did before I ever stepped into a studio with Jim Gaines. I probably knew his discography better than him—meaning: he’s a rock star in my eyes. So, when I walked in and made the record with him with Royal Southern Brotherhood, he just became like an uncle to me. He was like the cool football coach that you wished you had because you had the asshole one. He would absolutely dig in and find your strengths and magnify them. He was very, very good at that. The comfort level working with him was instant. As we were wrapping the record, I told him that the whole idea of the Royal Southern Brotherhood family from a musical and a marketing and business sense was that we would put out Royal records every year and a half to two years, but in the interim, we each would drop solo records. We have such a cool working relationship and I love him like an uncle and he agreed right then and there: “You call me and we’ll make time and we’ll make that record.”

I’ve got to say that it was very unconventional. I was wrapped up in touring the world with Royal, so I wasn’t at home in the studio cuttin’ demos, and sending them off to the label for approval and management for helping me mold the ones that were chosen for the record or the producer. In fact, my record label, Jim Gaines, and my management company were all quietly—they later revealed to me—really freaking out. They had heard nothing of what was going to be on this fucking record. They started to show hints of it, and then I started throwing them a couple bones just because I didn’t want to totally freak them out, so they heard a couple demos the week before I went in. They at least knew the area that I was going. That wasn’t by design. I wasn’t trying to be deceptive. I had no time. There was just no time to do this. I had in my head the songs that I wanted to do. I hoped and prayed that they’d come out good and that there was some kind of cohesion, some kind of linear thread that would tie it all together, and thank God that there is because that wasn’t by design either. Thankfully, I think that all these little babies make a nice family, and that’s the Great Creator right there. Anytime, you’re going to have Yonrico Scott play drums on your record and Jim Gaines producing it, you’re headed (laughs) in the right direction right off the bat.

No Comments comments associated with this post