The Del McCoury Band has just released their new studio album, The Streets of Baltimore, a focused ensemble piece which finds the band cutting tracks without too much prior rehearsing or fine-tuning. That attention to the live experience, such a hallmark of their stagecraft, translates well to the studio on this extraordinary work. The thirteen-track collection also features an impressive roster of songwriters, while giving their legendary leader a chance to acknowledge some past influences and inspirations, work with some material written by old and new friends, and present an old image within a fresh framework.

Jambands.com caught up with Del McCoury after a two-night stand at the Gentlemen of the Road festival, an event hosted by a handful of acts, including Mumford & Sons. It is fitting that the McCoury Band continues to build a bridge between generations. Indeed, their timeless music—both on stage and in the studio—has been equally inspiring in 2013, as it was so long ago when the frontman first began his musical journey in the 1950s, a time which saw Baltimore, itself, playing a key historical role in the development of not only McCoury’s career, but the bluegrass genre, too. As always, the bluegrass artist himself is jovial, lively, and always warm and humorous, as evidenced by his numerous breaks to offer a witty aside, comment, or guffaw. He is also a master of his craft, and he does not show any sign of slowing down, even as he sails along at 74.

RR: How are you, sir?

DM: Doin’ good. I just got back from playing in Oklahoma at a show out there with Mumford & Sons. We were there for about two days in Guthrie, Oklahoma. (laughs) They had a big crowd out there, man.

RR: How was the reception for you and the band?

DM: It was great; it was. They let us come in town. They had a couple stages, one out and one main stage. I never did get out to where the main stage was; it was out in a field and it was big. I think the boys went out there. After Mumford & Sons got done, both nights, we came on around 11 o’clock, and they went off about 10:30, and we went on from 11 to around 12:30, I think it was both nights, and, of course, Marcus [Mumford] would urge everyone when they got done to come up to our show—it was around the Main St., kind of in the middle of town. People as far as you could see, man. There were a lot of folks there. (laughs) Marcus came up the first night—we played there Friday and Saturday nights—and he came up with his fiddle player, Ross Holmes, who lives in Nashville, I think, and he got up and sang one with us [“Angel Band”]. Jeff [Austin] came up to play with us, as well, as did Larry Keel and Danny Barnes. The Keels were on this program, too, so I had them get up with us that first night.

RR: You had Keller Williams out there that weekend, too.

DM: Sure, my boys and Keller. They did a show both nights. They sure did.

RR: Let’s talk about your new album, The Streets of Baltimore. It is your third album in a row that, in a way, makes a different personal statement. In 2011, you had the collaboration with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band on Legacies. In 2012, you recorded a tribute album to your early mentor, Bill Monroe – Old Memories. This new album is not as concept-driven, but it does get its title from an important American city in your development. How did Baltimore play a role in your history?

DM: Randy, I would say it is because I got my break there to play with Bill Monroe in that town. I was playin’ there and he came to town and he was goin’ to New York City back in 1962, I think. I was playin’ in a band and Jack Cook was the leader of the band and I was playin’ in Jack’s band and he was the bluegrass guitar player/lead singer, so I was playin’ in his band and [Monroe] needed Jack to go with him to New York City, and it just so happened that they didn’t have a banjo player, either, so he took me along and he offered me the job. As you know, that’s how I got to know Bill Monroe.

It’s actually quite a big thing for me, but I played quite a bit in that town, too, probably with my own band after I quit Bill than even before I went to work for Bill. It was a town where a band could get work in the clubs and bars. I lived in the country, in York County, PA, and I was out there in the country. You almost had to go to the city to get work playing music. (laughs) And, you know, the first bluegrass band to ever play Carnegie Hall was there in that town, Earl Taylor & the Stoney Mountain Boys. He was playin’ seven and eight nights a week, man. They went up to New York City and played Carnegie Hall and they got put them on Folkways. They didn’t have a record deal or anything, and, so he got a big break but he never really did well. He left Baltimore and went to Cincinnati. He was kind of a guy that just moved around a lot. (laughs)

That town was really big for bluegrass in the day. I think a lot of musicians migrated from the south, or they came up there to get work during the war in the airplane factory, or the steel mill, or the shipyards, and they would get work there during wartime. A lot of them were musicians. They would work and, sometimes, play music at night. Sometimes, they didn’t; they just came—the musicians migrated with the workers. (laughter) The same with Washington, D.C.—they were both popular with music in the 40s and 50s. I guess I started playin’ there in the 50s.

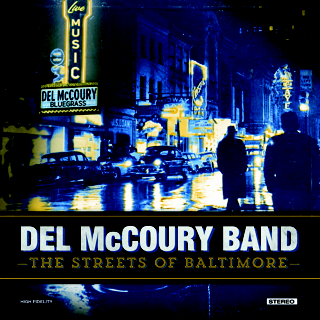

With this record, I thought I should do that song [“Streets of Baltimore”], which was written by Harlan Howard and Tompall Glaser, because he wrote about the streets, and I felt that I need to record that song because I owe a lot to Baltimore. (laughs) I had most of the material for the record collected before I even thought about Baltimore, but, in the end, I thought I should put a song on there about Baltimore. I think if I had thought of it earlier, I would have probably did more songs that I used to sing in the clubs of Baltimore. (laughs) That was kind of the way it came about. My manager said we should just call the CD Streets of Baltimore. He got pictures from the archives of the city. Of course, the one big sign with my name on it is not real, but all the rest is. The clubs we played in—if it had a marquee, you were lucky. (laughter)

Baltimore was a place where longshoremen would come in after being out on the water for a year and, man, it was dangerous. Of course, when you’re young, you don’t think about that. But those guys were shootin’, throw knives, and everything. (laughs)

RR: Do you ever get to those sections of the city these days?

DM: Well, you know, one time I did play a place downtown there somewhere, but it wasn’t anything that I had played years ago. (laughs) But, no, I really don’t. For the most part, I don’t play anywhere that I can think of around Baltimore anymore. I’m playin’ at a place called the Hamilton that I believe is in D.C. soon comin’ up [November 30], but I’ve never played there, either. I used to play at a place in Annapolis, but I haven’t played there in a long time, either. We’re just all over the place.

I don’t think Baltimore is as big for bluegrass as it once was. That’s my opinion, but back in the day, I used to know all the bands that were in that town. It’s funny; they were all cutthroat musicians. One guy would be playin’ a bar, and another guy from another band would come in and tell the owner, “Look, how much are you payin’ these guys? I can play cheaper than them.” (laughter) It was a cutthroat business.

RR: Does the scene appear more collaborative these days, with musicians working together, or it is just a different world in 2013?

DM: I think it is. I don’t think it is like it used to be. (laughs) But I tell you what, a lot is owed to a D.J. that was in that town named Ray Davis. He had a radio show on WBMD, which is a Baltimore station. He worked for a car dealership up on U.S. Route 1, Harper Rd., that went through Baltimore. U.S. Route 1 and U.S. Route 40—they both went through that town. Back in them days it was before beltway, too. Anyway, Ray had this dealership as a sponsor and he had his radio show up above the showroom. That is where he did all of his broadcasting from. He had recording equipment and he would record bands—mainly bluegrass, he was into that—but, he booked a lot of the Opry acts, also, all around that city. The thing was that he had the outlet for advertising because he had a radio show. He had a lot of listeners. It was a great thing, really. He would book Bill Monroe, he’d book Don Reno and Red Smiley, he booked the Stanley Brothers, and he would record the Stanley Brothers. They did a lot of records for Ray back then. I did one myself for Ray after I quit Bill Monroe, and it was never released. I can’t remember why, but it wasn’t. That was part of the success of bluegrass in that town, also, you see. There was a guy there that really pushed it on the radio and he would book shows. He was probably not legal. (laughter)

RR: He was a D.J. and a publicist, and a producer and a promoter, too.

DM: (laughs) That’s everything he was into, you see. I’m sure there was a conflict of interest somewhere. One thing he didn’t get into—I don’t think he ever got into managing a band. (laughs) I think that was the one thing he never did. He did a lot of other things as far as music goes—radio and the live performances—but he would book these bands. He’d book them in clubs and parks, like New River Ranch, which is north of Baltimore, up towards, almost to the PA line, goin’ up Route 1, and he would book bands into that place: George Jones, you name it, everybody from the Opry, including Bill Monroe, and Flatt and Scruggs and Reno and Smiley and Jimmy Martin and the Osbourne Brother and just everybody. They could depend on him. Mac Wiseman played a lot for Ray. He provided a lot of work for bands. Also, if he had one of those major bands, he’d get a local band for openin’ the shows. That was really great.

I sang on Charlie Louvin’s last record [ The Battle Rages On ] on “Weapon of Prayer.” For some reason, somebody mentioned the parks in that part of the country, and he said, “Me and my brother [Ira] were playin’ at New River Ranch, and it was only ten miles to Sunset Park, which is up in PA on the same highway, Route 1, and he said this other Opry act cancelled on account of sickness or somethin’ that was gonna play the Sunset Park, and it could have been anybody from Ray Price to Loretta Lynn to whoever. I don’t know. He said they had to cancel, and Sunset Park called him and wondered if he could do a doubleheader—play one park in the afternoon and then come up there at night. They always had two shows—one in the afternoon and one in the evening. So, they did a doubleheader there. They played and ran ten miles down the road and did another show later. (laughs) They did one in Maryland, then they drove ten miles to PA and did one. Then, they drove ten miles and did an evening one, then they drove ten miles back up to PA and did another evening show. (laughter) They needed somebody from the Opry because they had booked an Opry act that couldn’t make it. They figured, “Yeah, we’ll do that,” but they were pretty young then.

No Comments comments associated with this post