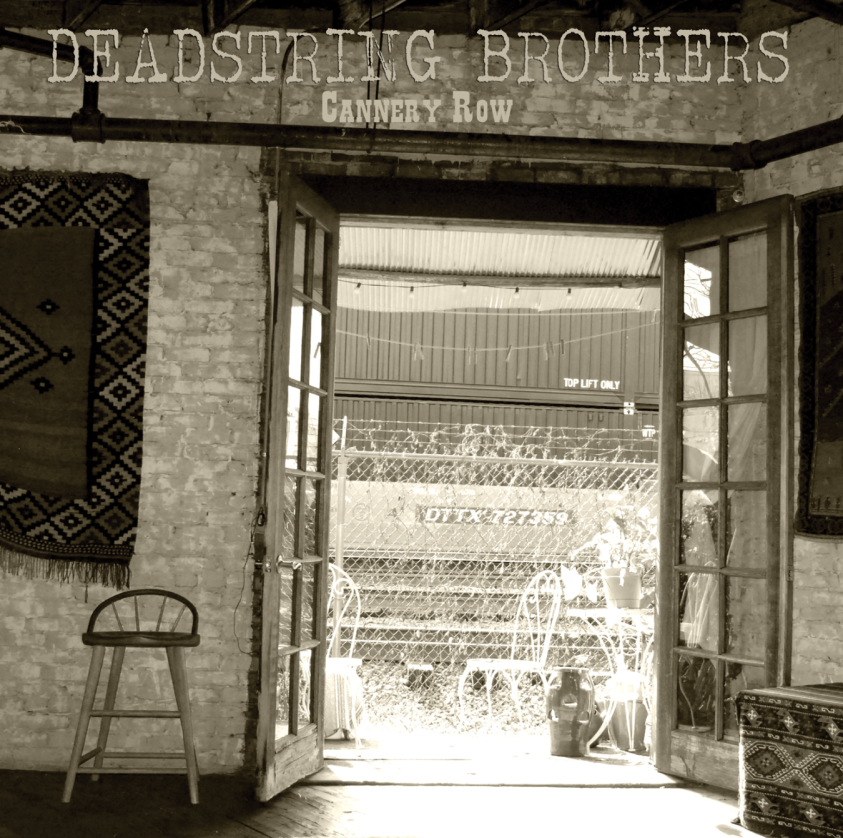

There was too much stainless steel in the bar to make me feel comfortable. I prefer bars of wood and stone, places where they have signs to remind the patrons not to wear motorcycle club colors and not to carry weapons. I live in the woods and this was Philadelphia. But it didn’t matter. Later, the Deadstring Brothers would play upstairs and I was eager to see them. Their latest album, Cannery Row, has been in constant rotation for me since it came out earlier this year. It is an album that is one of the year’s finest releases. It has a simple, poetic beauty to it that deepens with each listen. It is good early morning music or late night music, depending on which side of the sun you spend your hours with. The Deadstring Brothers have put out five albums now, most with the superior Bloodshot Records, with a sixth on the way this coming April. Before the show I was to sit down with Kurt Marschke, the lead singer, guitarist and songwriter for the Deadstring Brothers. Kurt has been the focal point of the band since its inception, though he now has a steady partner in crime and like-minded musician in the Deadstring’s bassist, Jeremy Mackinder.

I drank and waited and listened to the traffic on the street.

Jeremy entered the bar and stretched. I introduced myself and offered him a drink.

“I’ll take a whiskey,” he said. “Our damn van broke down. Fuel injection went. So we had to rent that thing, strip down to the essentials, and haul ass to get here.” He pointed to a minivan parked alongside the curb with its blinkers on. Jeremy is not a small man. Tall and thick, that minivan must have been awful for him to ride in.

“To hell with that thing,” he said. “Can’t get comfortable in it.”

I grabbed us drinks and handed him his whiskey.

We toasted.

“Kurt will be here in a moment. He’s unloading.”

We leaned against the bar and talked.

Later, Kurt came down from the soundcheck and we sat at a table on the sidewalk. He didn’t order beer.

I put the recorder out on the table and told him I wasn’t much of a question-and-answer kind of guy. We’d have a few, talk and see where it took us.

Kurt laughed.

“It’s been driving me crazy,” I said, “that you guys have put out this phenomenal record and just get dogged in the press.”

“It’s not dogging,” Kurt said.

“No? All those ridiculous Stones comparisons?”

“Well, that. People are just kind of hung up on that thing. But that’s just lazy journalism.”

“Absolutely,” I said.

“But there’s been no unfavorable reviews.”

“How could there be? It’s a hell of a record.”

“It just has a lot to do with where we are as a band. Different journalists would give it a different kind of attention. But, that said, none of the records have gotten beat up.”

“No. But do you think you’d get a different kind of press if you played the game a bit more? I mean, here you release an album that is like a short story collection, the way the songs play off each other. About all these people struggling against horrible odds. Most people don’t want to hear that.”

“Is that what that record was about?” Kurt said.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Me either,” Kurt said.

We laughed.

“Look,” I said. “On the way down here I listened to your first album. In ‘I’m Not a Stealer’ you’ve got that line about leaving town. Now, in ‘Oh Me Oh My’ on Cannery Row, you write a similar thing, a similar sentiment, but it’s very different. You’ve got characters on this new record.”

“Yeah, but this was also my perspective as well. This was me living in Nashville and kind of creating characters around Cannery Row, this loft I’ve been living in. I was creating characters out of stuff that was going on. But that record, in many ways, was the most autobiographical I have ever been. Of course I’m still using a ton of metaphors and what not. But see, we were really short on time to make the record. We had five days. Most of that stuff was written on the fly. There was a lot of being under the gun and having to write something so that we could record it tomorrow, you know?”

“So you reached for what was right there,” I said.

“I did. A lot of that was why I said to myself, ‘I have to do this now, about what is going on now.’ I wrote the song, ‘Cannery Row,’ first. It was the platform for the whole thing. The whole record came from that one idea, writing about that one area. Living in this one area. That was the catalyst to keep me focused under such time pressure. There’s other things in the record beyond just that area. But that was the starting point. I had to get it done and I couldn’t fudge it.”

“It doesn’t sound like you did,” I said.

“See, that area is a historic area, a bunch of old brownstones all owned by these two brothers. It’s going to become an anomaly because it’s getting built up around it. Because of the convention center. Gentrification. I had that whole area, Cannery Row, that unique little area and community and that’s what I used. And some of it is dying out.”

I sat back and drank. I thought of the farm where I work as a farmhand and how the guy who built it in 1760, a farrier, now wouldn’t be able to afford to buy the house he built doing the same work. I told Kurt as much.

“But that’s everywhere,” Kurt said.

“It is. But it also means you’re losing something, too. That’s what I appreciated about Cannery Row so much was its accuracy of description. Of nailing down what it feels like, and means, to struggle in a life that is dying out. That’s being consumed,” I said.

Kurt drank from his vodka and tonic. He sat back.

“Part of it was development as a songwriter. Getting to know the craft a bit better. This was the fifth record for me as a writer. Some of it might be a bit of maturity as a writer.”

“Talk about the craft of being a songwriter,” I said.

“I’m not good at talking about that,” Kurt said.

No Comments comments associated with this post