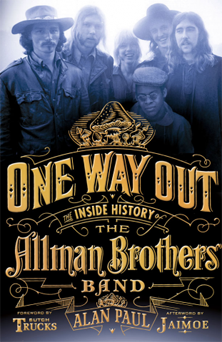

For as public as The Allman Brothers Band’s saga has been for the last 45 years – a mix of magnificent triumphs and macabre tragedies; dues-paying and wretched excesses; clashing egos and brotherly love – their story has never been righteously told … until now. When author Alan Paul says that writing One Way Out – his brand-new oral history of the Allman Brothers – “took a pound of flesh” out of him, there’s no doubt but that it did – to do it right.

Paul – a welcome friend of the band and their inner circle for years – manages to present the Allman’s story fairly. There’s the good, the bad, and – sometimes – the ugly, but as guitarist Derek Trucks once told Paul, “If it happened, it happened.” Paul used an oral history format for much of One Way Out, letting those who lived the tale tell the tale. The result is an engaging book about a legendary band that both the seasoned Peach Corps veteran and the casual fan will enjoy.

We had the opportunity to talk with Alan Paul about his labor of love … which, as it turns out, began when he was 12 years old.

BR: Alan, first of all, let me congratulate you – this is quite a piece of work, man.

AP: Thank you very much. It’s wonderful to have it out there, of course – and it’s a bit surreal. I’ve thought about this book for 20 years and worked on it very actively for three years. Now it’s done; it’s here; it’s in my hands – it’s a great thing.

I feel like it was mine and now it’s everybody’s … and I love that.

It’s so obvious that One Way Out is the work of somebody who knows the music. When did you first get hooked on the Allman Brothers?

I heard them on the radio all the time during the era of Brothers And Sisters and I was attracted to them, but when I was about 12 years old, my brother – who was four years older than me – gave me a copy of Eat A Peach. He let me sit on his carpet, listening to it on his big stereo for hours on end. This would’ve been the days when you were only as good as your stereo and my brother had a nice one. (laughter)

I hear you: my older brother did that for me … only at the time, it was Johnny Cash. (laughter)

It’s a proud tradition with older brothers and sisters. (laughter) I’ve talked about it with Warren Haynes, actually – he had an older brother who did the same thing for him. In the movie Almost Famous, there’s the famous scene where the lead character’s older sister turns him on to music like that.

So I sat and listened to Eat A Peach with the double album in my lap … and the psychedelic artwork on the cover played a huge role in it, as well. I didn’t know what it meant … I’m not sure how much I understood that it was drug-related. I think I did; it’s just hard for me to recreate where my young teen mind was. But it just fascinated me.

What was really cool was I did an interview on a national radio show for my last book – Big In China – about this topic and I mentioned this same incident. After it aired, I got an e-mail from David Powell – he’s the artist who created the Eat A Peach album cover. He happened to hear the interview … and it was such a cool moment for both of us.

For David, he knew he’d done great work, but it was a long time ago and in a different life … he’s an art professor at SUNY Plattsburgh now.

Cool! (laughter)

Yeah! And he hears this guy on the radio talking about how this art inspired him to be a writer and love music and everything.

And for me, I felt like a 12-year-kid again when David wrote me – to get this message out of the blue. To me, David Powell is a holy man – he created the album cover for Eat A Peach … one of the iconic images in rock. And I’m really, really pleased that I got the original art from David to use in the book, as well.

So this really all comes back to your brother, right? We should give him a shout-out here.

Yeah, absolutely: David – David Paul. I dedicated the book to him.

Rightfully so. So you got bitten at the age of 12 or so …

And the Allman Brothers have been just wrapped up in my life since then. In the 8th grade, I chose Duane Allman as “The Great American” in Social Studies. Not sure what my teacher Miss Zack thought about that – but I wish she could see me now. (laughter) I wasn’t just a bum, Miss Zack – I had a plan! (laughter)

Of course it took a few decades for the plan to play out … (laughter)

And then in 1990, when the band had just reunited for Seven Turns, I did a story for Tower Pulse magazine – that was the first time I did something professionally. My early love for the band came back; I interviewed Warren, Allen Woody, Dickey Betts, Gregg Allman, Phil Walden, Tom Dowd – everybody I could think of. That was just a huge thing for me; it was the best story I had written at that point by far because I had thrown myself so into it. That piece sort of indirectly led to me getting a job at Guitar World in 1991.

I had that early love for the band – but when I saw them in ’89 and ’90, it deepened so much. I was also seeing the Grateful Dead at that time, who I liked a lot … but what they were doing at that point in time paled in comparison to what the Allman Brothers were doing.

When I saw the Allman Brothers, I couldn’t believe how good they were. I didn’t know who Warren Haynes was when I saw him for the first time, but he was standing up there toe-to-toe with Dickey … and Dickey was really still very much in his prime. It was very powerful.

Then I moved to New York and got this job … and the Allman Brothers were in full swing. The next year the Beacon stuff started and they were around so much; I just started spending more and more time with the band and people like Kirk West, who was their road manager – their “tour magician.” (laughter)

Those relationships developed over the years – it wasn’t like I’d been hanging around in the back thinking, “Maybe I’ll get some good stuff for a book” – I was there because I wanted to be. My relationship with them was born out of a deep love for the band and it was something that was shared. I just had this incredible passion and appreciation for what they were all doing.

Is there any one moment that comes to mind as far as your relationship with the band affecting how you approached writing the book?

Yeah. At some point in the process, Butch told me something that really impacted me: Duane said to the guys – in words and in example: “If you’re going to have a band, you ought to have the best band you can have … be the best band in the world.” And I thought, “I can’t honor these guys and their music and their legacy unless I make every effort to write the best book I can – to try to write the best book in the world.” It’s not to say that’s where you’re going to end up … but if you’re not shooting for it, what are you doing?

Butch telling me that really made me feel like I needed to up my game.

So, you had a stockpile of interviews before you officially began working on One Way Out.

Oh, yeah – when I started writing the book, I already had 20-some years of interviews. What’s funny is, I thought I knew everything there was to know about the band – certainly more than the average guy – but as I started to do new interviews for the book, I realized it was arrogant for me to think that I knew where the holes were and I just needed to fill them in. I started to learn things; and I realized you can’t do the interviews and just look at the A, B and C. You need to start asking questions and talking and see where you go … especially with people like Kim Payne and Willie Perkins – guys I got to know through this book. I had to go back to them multiple times and each time it got better and better because they began to trust me; they saw I was asking appropriate questions and taking what they said seriously.

You have to put in the time to get the real stuff. I tried to take it very seriously.

So when it was all said and done, how much of your archival material did you use in the book?

A lot. There were a few things that were frustrating to me on that count, though. For instance, I interviewed Phil Walden several times – but I only interviewed him in-depth about the early days of the band forming. I had my notes – which is amazing – but I could not find the original tapes. Phil was alive for many more years after those interviews and I could have called him up and had many more conversations with him … I kick myself now. On the other hand, I was happy to have what I had.

It varies from person to person – with Tom Dowd, I was able to interview him a number of times and some of it was published, but a lot wasn’t. I did an extensive story on the 30th anniversary of At Fillmore East, for instance. I went back to those original interviews and – you how it is when you do a magazine piece – I’d talked with Tom Dowd for an hour but used maybe five quotes.

Absolutely – sometimes you have to boil it down to the syrup.

Listening to those old tapes, I might find only a couple lines or maybe a paragraph that I hadn’t used before – but sometimes it was a very interesting paragraph … enough for me to go back to people ask them about this or that little interesting tangent.

It was a bit of a jigsaw puzzle, really.

No Comments comments associated with this post