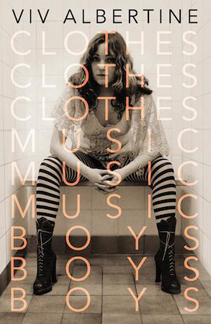

As a guitarist and songwriter for the all-female punk band The Slits, Viv Albertine was a resident of and participant in the London epicenter of the mid-‘70s musical revolution chronicled in her memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys. Leading an engaging, often heartbreaking journey through life, with relationships with The Clash’s Mick Jones and Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious only a part of Albertine’s story, she continues today to be a strong, outspoken, and honest representative of her gender and that gloriously raucous era, as she spoke to us from her home in England. As the ensuing conversation affirms, the pioneering British musician remains the outsider’s outsider.

The amount of detail in your recollections was incredible. Did you keep a journal growing up?

I never kept a diary, and I remember in punk times thinking I should be documenting all this. I just knew I wasn’t that sort of person. When I sat down to write the book I thought, I’m only going to write about the moments in my life that have imprinted themselves emotionally. I’m not going to go and talk to people and get their view. It is all about a woman, in a way, a female’s point of view. And I never forget what I’m wearing.

I couldn’t believe you could remember what everyone else was wearing, as well.

That’s what my mum hated about it; that I did remember what I was wearing and what others were, as well, and I didn’t remember my lessons, or historical facts, or geography. I’ve got a very selective memory, and clothes, music, and boys I do remember.

How did you decide on the book’s structure?

Each chapter was like a track on a record. Because of my punk schooling, my chapters had to be succinct, finished properly, know what they were saying, be honest, and no clichés. I sort of half-wrote it with the thought of young girls in mind; a very, very honest talk with an older sister or something. Not often do they get to hear complete honesty.

Each chapter leads with a quote as a kind of subtitle, like a subtle clue to the following content.

The quotes were so important to me. In fact, although I never kept a journal, I have written down quotes all the time. My lyrics book is full of quotes. I really wanted the quote to be right for the chapter. Some of my favorite and most satisfying moments were getting the right quotes, because I had to get permission from all the writers or their estates, and I didn’t get turned down for any of them which is fantastic.

Your battle with cancer was written with that intended, matter-of-fact quality. Certainly that’s one place where no one would’ve blamed you if you had been less honest and succinct.

Being sandwiched between two covers, put in a book, slightly condenses your experiences and puts them all on a level. The cancer thing lasted years, but in the book I couldn’t talk for all ten years. I tried to convey that I was dead to the world, that I had no life, no confidence, no spark, and that was a result of fighting the cancer. That was as low as I could be. It’s very hard to write that for ten years, ten dead chapters.

It seemed almost like the next logical step for you, having gone through so much, to take on cancer in the same way you did anything else, as a challenge, yet your honesty also felt courageous.

I’m no brave person. I was a shivering wreck, and I was an unpleasant person during it. Maybe I’ve been slightly schooled, coming from nothing as a kid, being in a sexist society and the male world of music, maybe that did toughen me up a little more than I thought.

Why was London ground zero in the mid-70s for punk?

Whether evolution or revolution, it isn’t one little lightbulb moment. Its threads coming from all different places. Geographically where we were placed, there’s a lot of black music influences from lots of ports around the island. Nicking stuff off New York guys who were five years older than us- the New York Dolls, Richard Hell- a bit of it all. It was filtering in from all different places.

Do you see the influence of punk today?

I definitely see it, but of course, over the years it gets warped and watered down and becomes commercialized. Everything that stood out a mile when we were doing it, and was hated and rejected- we were abused, and stabbed, and spit at for doing what we did- has now become consumed by the West and turned into a commodity. Music back then used to be made by outsiders, and music now is made by the ruling class. The ultimate message behind punk, to burst out of your chains, don’t be told where you can be put in society, make yourself heard even though there is no place for you in this world as it stands now, is sort of not relevant. It’s not a parallel anymore because all these middle-class kids are doing it. Really, they are acting it. They are not living the life. They’re not living the life of being desperately poor because they have chosen a path that wasn’t easy. They haven’t thrown their lives to the wolves.

Where do most often see that punk influence?

I’ve been to loads and loads of festivals, and every stage I pass sounds like regurgitated music from 30 years ago. Yeah, I can hear punk in there. Yeah, I can see punk in the way they dress and snarl. It isn’t the essence of punk. It’s pantomiming punk. It’s still fun music. It’s not radical music. It’s not revolution. And that’s what punk was.

Your description of what punk was- radical, revolutionary music that was made by the poor and working class- can’t help but make me think of Bob Marley. Was Marley, in his own way, the ultimate punk?

No, because he was sexist. The Slits were dealing with personal politics. The history of women has been belittled because so often it deals with personal politics, but Marley, as a male, was dealing with more party politics. He was fighting his fight as best he could in Jamaica, and it resonated at certain levels, but he was dismissive of The Slits. He made good music. I can’t ever say he was a punk.

Was his dismissal of your music public or something relayed to you in private?

He did “Punky Reggae Party,” and he listed loads of bands (in the lyrics). Because our manager, Don Letts, was also a Rasta, he told him about us and put our name on. When (Marley) heard we were girls he took our name off the record. So, he’s no god to me. I don’t have gods. Rasta in the ‘70s, I don’t know about now, but in the ‘70s, it was incredibly sexist and traditional. It wasn’t particularly open-minded. There’s no way I will say Bob Marley was a punk. He was what he was, and we loved his music, but we preferred heavier dub to that anyway.

You can see a similarity between the genres, in as much as they both came from disenfranchised youth?

I think that’s why punk, so much, responded to reggae. Apart from the fact that it was stripped down, especially dub, very unembellished, and it was about rhythm, it was music from the streets. But they were very sexist, all these guys.

No Comments comments associated with this post