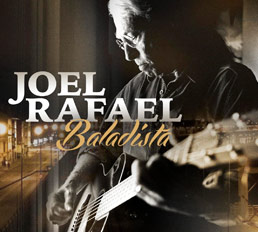

Joel Rafael started playing music in his home state of California in the midst of the folk movement of the 1960s, and although he holds an appreciation for certain elements of rock music, he remains a folk singer at heart. After several albums, including two records comprised of Woody Guthrie tunes—both covers and co-writes from Guthrie’s unfinished lyrics—Rafael has recently released his newest album, Baladista. A stripped-down and intimate affair, the record illustrates Rafael’s skill in songwriting and lyricism, elements that tie him and his music directly to the original roots and spirit of the folk genre. He recently spoke with us about the new album, but first we took a trip back to his beginnings in California, exploring the music that defined the era, and discussed his work with Woody Guthrie’s music, a catalogue that has inspired musicians for the better part of a century.

How did you get started in music? Was it something that was with you at a young age?

Well I was drawn to it at a young age, and I think a lot of kids are, because music is something that speaks to everybody. But I was lucky, because when I was a kid in elementary school, the schools that I was in out here in California had really good music programs. And so as early as the fourth grade, they were recruiting kids from the classes to be in the band program. So I signed up right away. I had already had a little bit of experience, because I had an older brother who had taken accordion lessons, and so I kind of followed in behind him and did that for maybe a year or something. But then I started playing drums in the school music program. I learned a lot of theory and I learned a lot about tempo. Then when I got to be a teenager, the ’60s folk movement was just starting to blossom. All of a sudden, my friends were getting acoustic guitars and starting to play Kingston Trio songs and Peter, Paul and Mary songs, because those were the first folk songs that were sneaking onto the radio, which was pretty restrictive, maybe even more so than it is now. So I had to get a guitar, because there was something inside of me that really wanted to sing. I was a singing drummer already on a couple of songs in the little garage band I was in. And so my parents took me down to Tijuana, and we found a very inexpensive Mexican guitar down there. That was my first guitar, and I started to learn some folk songs, playing my friends. There were a few little groups of people, little cels of kids that had gotten together playing music. It was just a really magical time, and it was my indoctrination into melody and music and singing and writing. I knew I was going to get into music, but I didn’t know exactly what direction it would take until I had an acoustic guitar in my hands.

What was the music scene like when you were growing up, and how did that change, especially during the ’60s music movements?

When I was a kid, I listened to a lot of music, because my parents had a really good record collection. But it was mostly stuff that was probably between the ’30s and the early ’50s—so lot of big band music, crooner singers, some of the great black artists like Lena Horne and Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong. Then there was stuff being played on the radio, which I’d call the early rock and roll, then there was kind of the standard radio that was still playing crooners and that kind of stuff. So that’s what I was getting exposed to. When I first started playing in the garage band, we started to have a couple of vocals, and they were kind of like the songs from the old rock and roll—The Everly Brothers stuff and Buddy Holly-era songs. But to tell you the truth, to me, as a kid, because of what I’d been exposed to through my parents’ record collection, I was more drawn to singing that was a little bit more refined than the early rock and roll singing. A little bit more like the sound of an experienced singer. I didn’t have any training, just like everybody else, but that’s what I was going after. I was actually influenced a lot by Al Jolson, because my parents had a couple of his records, and there were a couple of movies that aired on television when I was a kid, repeatedly, biography movies about him that kind of caught me up—the music part of it, and him as an entertainer and how he changed things in popular music, that kind stuff. So I moved in that direction. Then I was lucky enough, about the time I was in high school, to get my hands on a better guitar, and then started to branch out into other kinds of music besides folk music. There was a lot going on in the mid-’60s, musically. Like The Beatles was the huge phenomenon. When we started to hear their music on the radio, it was just so completely different from anything we had heard. It was related to everything we had heard, but it had an element to it, a coolness and hipness to it, that we hadn’t experienced before, you know? I think the first song I heard by The Beatles was “I Wanna Hold Your Hand,” and when they went to that high harmony, you know, like, “I wanna hold your hand.” When they went up there, it just kind of blew my mind. I hadn’t heard anything like that before. We hear it all the time now, but at that time it was brand new. So that kind of inspired my toward electricity, even though I had been kind of resisting it up till then.

How did that electric influence change the music you were playing?

When the English invasion happened, all of a sudden rock and roll music—or I should say the electric element of rock music—had more of an appeal to me. I didn’t really want to be a rock and roller so much, but I wanted to take the sounds of electric instruments and combine then with what I was doing. Whereas most of the folk groups were all acoustic—even the basses were stand-up basses—I really liked the fluid sound of an electric bass, so I thought I’d mix that in. I really moved in that direction when that folk rock thing happened, and that’s always kind of been my M.O., musically. So consequently over the years, as I’ve developed as a performer and as music has evolved, I’ve kind of found myself a little bit in between genres. Like the folk people, they’ve always kind of thought I had a little bit too much pop and electricity going on in my music, but the rock people always thought that my music was way too folk to be in their world. So, for some parts of my career, it’s been kind of a loner path, but then other times—like right now, everything’s kind of coming together in a real nice way, with this new record and stuff. I’ve done different things, but this record is actually an evolved development of that original idea when I first started playing folk music. And what I do now is very much called folk music—it almost is considered traditional, because things have changed so much. I had some influences early on, but those influences, at a certain point, if you keep at what you’re doing, they kind of distill into, you know, who you are as a person. It’s just who you become. Then after that, you’re kind of stuck with it—that’s just who you are, and so you have to make the best of it. Arlo Guthrie has actually said this before of his dad, and it’s sort of a guidepost for me—Woody Guthrie’s philosophy was it’s better to fail at yourself than to succeed at being somebody else.

When that first draw to the electric element happened, was there any resistance, maybe not from you, but from your friends or other groups?

You hear the stories, and there’s things that become like myths, down through history. One example would be when Bob Dylan went electric at Newport Folk Festival. I’ve known about Newport Folk Festival since I was a kid, because it’s been going on for so long. It’s a really vital festival, and there’s a lot of great young acts there. I actually finally got to be on it in 2012 as part of a Woody Guthrie centennial tribute. And I went there with just my acoustic guitar and harmonica. It was kind of funny, because I was maybe one of just a handful of performers who performed that was. Literally everybody else had a band. And my joke on stage was “I hope if doesn’t ruffle any feathers today—I’m going acoustic.” Because the whole myth of Bob Dylan going electric at Newport. But if you talk to people who were there, there’s a whole variety of stories of what went down. Some people say they’d been presenting an element of electric music for a few years before that happened, even. It was just the fact that Bob Dylan had gone electric. But that was a transition point, definitely. There was a divide between traditionalists and modernists at that time, and I think it’s a division that never has really gone away. It’s sort of been the catalyst for the argument, “what is folk music?” Because everybody always tries to define it, you know. “Real folk music has to have this, or has to have that.” But I don’t subscribe to any of that stuff, myself. Genres are all well and good, but they’re just for people to be able to get a handle on what we’re talking about, conversationally. But music is music. It’s an international, universal language that permeates every form of life, from the sound of the wind and the ocean, the birds and the bees, to people actually making instruments and imitating those sounds and coming up with melodies. It’s something that’s been around since the beginning of time, and it’s something that everybody understands. That’s how I see it. There are divisions, and I’ve felt that from time to time. I’ve felt like I’ve been on both sides. Not that I’ve taken the sides, but that I’ve been sort of placed on one side or the other by folks. But I don’t place myself on one side or the other. I’ve kind of come to peace about being called a folk artist, though. That’s always where I get put, in terms of definition, and I’m okay with it. They have a lot of names for things, and folk music—that’s a good thing.

No Comments comments associated with this post