During a three-year period that included two album releases Jellyfish swam upstream against the tide of hair metal and grunge that permeated the music landscape. Headed by Roger Joseph Manning Jr. and Andy Sturmer, the duo crafted a pop sound that featured the hooks of the best bubblegum pop with harmonies that would make Brian Wilson smile and lush arrangements that offered sonic pleasures on repeated listenings.

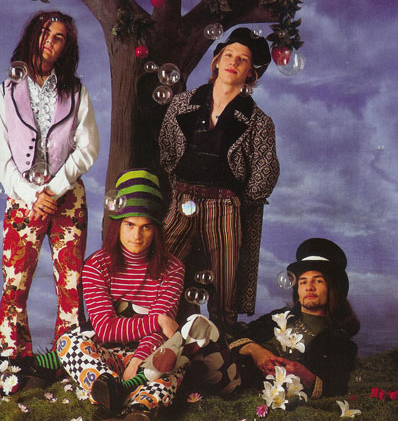

Wearing outfits that looked like they were stolen from the set of a Sid & Marty Krofft psychedelic kids show, Jellyfish didn’t stand a chance of breaking through to the mainstream success it deserved. Instead, the band brief impression left a legion of devotees to look back at the material on Bellybutton and “Spilt Milk” with the fevered attention it deserves.

Last year, Omnivore Recordings put out expanded deluxe CD editions of Bellybutton and Spilt Milk They include the original albums remastered plus 51 bonus tracks — demos and live performances.

The beginning and end of Spilt Milk presents an example of the intense thought process and care put into their music. It begins with the quiet, contemplative “Hush” and is followed by the rumble and roar of “Joining a Fan Club.” The album ends with “Brighter Day,” wherein the last note of that song fades out, revealing that it is the first note that fades in on “Hush.” The album is both infinitely listenable and a melodic piece of art. Jellyfish wasn’t ahead of its time. It was part of no time and aligned with every time. Some never got it. Some hated it. Others remain enraptured to it.

I spoke with Manning, who now is an integral part of Beck’s musical family in the studio and on tour, about his time with Jellyfish and touched upon his solo albums and work as a session musician. His recent contributions include performing and collaborating with Adele, Emitt Rhodes and Boots.

I was going to ask this later but since we’re discussing session work now, for someone who worked on your solo albums and Jellyfish, you have a degree of artistic control and do things from scratch. When you do session work, do you have to re-wire your mind and remind yourself that you’re here to serve this person or serve the song? How do you deal with it?

You mean, how did I kind of shift gears? Well, there was very little shifting to do because the only difference was that in a band like Jellyfish or Imperial Drag or whatever, I was 50 per cent of the writing collaborative process. But after the songs were written, you had this raw song idea that needed to be fleshed out with arrangements and performances. And that’s what I do on anybody’s music. I show up with the assumption their song is intact and then we go to work flushing out arrangements.

Obviously, what I would do arranging on songs that I’ve been a part of there’s already some immediate inspiration, that excitement and you kind of have a focus where you’re heading. It’s a little more challenging sometimes to come in raw.

Part of what I do as a session musician is try to get inside the psyche of the songwriter. I always say, “The song is king.” In other words, the song will dictate an attitude, an aesthetic, an environment that it’s the musician, producer and the arranger’s job to flesh out. Some songwriters are very clear with what they want the song to have arrangement-wise. Others have no idea. That’s why every session job is challenging and that’s part of where the fun lies. Some people really want a lot of your opinions on one project and others you don’t need to offer up your opinion. There’s music, just do as you’re asked. [laughs].

It’s usually the former. Usually, part of why me or other people get employed is because there’s an improvisational spontaneous attitude that we can bring to somebody’s record. It’s really fun. I’ve always had fun doing that, and I continue to draw fulfillment out of it. It’s one of many things I enjoy doing. It’s continued to serve me over the years.

I was reading an interview with you and they were asking what bands you are into, what bands Andy was into, and you alluded to that with your answer. You were talking about him being into Van Morrison and Bob Dylan. So, was he responsible for the foundation of a song and you brought in the harmonies, the arrangements and the lush aspects to it?

In the respect that, for example, you can say something as simple and obvious as Andy wrote all the lyrics in that sense. Andy was much more a fan of poetry and the written word, in general. Simply, by virtue of the fact that I had gone to music school and was very fascinated with arranging, the mechanics of that, I was able to bring that skill set to our collaboration.

We both had ideas for arranging. Andy may have a countermelody for a string part or a background vocal but I was usually the guy and I enjoyed fleshing out that idea. What does it sound like when a string section plays this idea or a group of people sing this idea?

Songwriting has always been two phases. For someone like me, it’s coming up with the chords, melody and beat – the music part — and then, with pop music you put the lyrics into that melody. I admire quality lyric writing. I certainly am opinionated about people whose lyrics move me and touch me, but ultimately, at the end of the day it’s not very important to me. I don’t want to sing foolish things or gibberish or nonsense. I’d like to be conveying some kind of thought that’s important to me but I’ve even heard, sometimes, that a great singer, their voice is so good and the song is so good, they can start reading out of the phone book. It’s still going to be a rich tune. I believe that’s true to a degree.

I’m just not compelled or as inspired by the lyrical component of the pop world than [I am] the music. That may even sound a bit hypocritical but I have been very fortunate to team up with two great lyricists in my collaborative years – Andy of Jellyfish and Eric Dover of Imperial Drag. For my solo records, like Catnip Dynamite, I’ve written all the lyrics and it took me forever to come up with that stuff. There are songs on there that I wrote in 20 minutes and the lyrics took two weeks, and I’m not exaggerating. I’m very proud of the lyrics that are represented on my solo records. I’m working on a third solo record right now and I teamed up with a friend of mine who helped. He’s contributed about 50 per cent of the lyrical content because it really helps speed things up. It helps move some of these songs along for me.

It wasn’t that black and white but Andy definitely, you can say, he wrote all the lyrics as did Eric Dover in Imperial Drag.

As far as the Jellyfish re-issues, did you listen to them?

Sure, because they went through a different mastering process.

What was your reaction to them, listening back with a critical ear?

The parts I did, the guitar I did, the background vocals — almost across the board I’m 100 per cent okay with the choices we made and how they held up. There are things I know now simply from making records for 20 years, that I know more about the recording process, the sonics, the engineering, the way the stuff sounds. And while Jack Joseph Puig, who engineered and mixed both records, is one of the great masters who lives among us, I would have voiced opinions or changes or had him do things differently because of I what I know now. I think stuff could have been represented in a way I would have preferred on some stuff.

But, as far as content, I’m at peace with it and happy that it stands the test of time for not only for me but a whole legion of fans.

As far as recording, is that correct that it took six months to record Spilt Milk ?

That sounds about right. We started in April of ‘92 and finished up in September of ‘92. That’s working, maybe there’s a week off here and there, five or six days a week working.

I’m listening to the demos on the re-issue and they sound pretty fleshed out and comparable to the final product was. What was it that made the album take so long?

Because, as you noticed, on the demos a lot of the ideas were already there. There is simply a process involved in wanting to achieve the best results. Say we had a guitar part on the demo that we liked and we thought was working. Well, now we need to recreate that guitar part for the album. That opens up a whole can of worms. You can spend hours or an entire day or more sculpting the right guitar tone for that one part and then you may want to make some changes or enhancements or try some…we tried to afford ourselves the luxury of experimentation and that takes time. So, while we said, “This guitar part’s working” but somebody might suggest, “What if change the second half of it?” Then, you’ve just got to audition that. Play with it and change it. And, of course, the computer’s not around. So, it’s always going to be slower on tape even though it sounds better.

And, it’s just the nature of the best. We did have the funds we needed from the record company to take our time and do what we wanted to do. Sometimes, you can get lost down a rabbit hole chasing something and three days later go, “You know what? It was good the original way that it was.”

Really, that’s it. There are demos from Spilt Milk that were just that. They were sketches. They weren’t completed or fleshed out. So, we spent time fleshing them out. Yeah, it’s the nature of the beast. I’m not proud of that. We didn’t want there to be three years between Bellybutton and Spilt Milk but between record company release schedules and the time it took to demo everything first…some bands don’t demo everything like we do. We made very, very elaborate demos because it was too frightening to go into the studio not knowing whether or not the majority of our ideas were solid. Andy and I had to believe 100 per cent, “Okay, this is working. This is mostly going somewhere. We feel that this is now fleshed out enough that we’re confident to be in the studio environment,” which can be very nerve-wracking, intense and the pressure can be more on you. The clock’s ticking. Money’s being spent. You don’t want to go in there with nothing, “I don’t know what we’re going to do on this song.” We didn’t want to leave it up to anybody but ourselves. Here we are 20 years later, you gotta live with it. We were trying to make sure that when this very day would come for ourselves and the fans…We really went over everything with a fine-tooth comb.

When you mentioned about computers and tape, you sounded like you’re a fan of analog. If you were recording a Jellyfish album now would you go the Pro Tools route because it could be cheaper and easier to do?

There’s a huge trade off and it’s one that I take advantage of all the time. For example, all my solo records including the newest one…well, that’s not true. The first two solo albums, they’re all done on computer. There’s no tape. I didn’t have access to a tape machine. This third one, I’ve actually tracked some drums and other instruments to tape and then being transferred into the computer. There are just huge conveniences and luxuries that the computer can afford and it helped me realize a lot of dreams and fantasies.

On the solo records it was important to me that I try to play everything by myself even though I know many, many wonderful musicians. If I played a guitar part on a song, I mostly got it but there are a few places where it’s just, “Oh, that’s not very good.” Normally, we would try to redo it again but there was charm in it or I really played the right note with right tone at the right time. Well, the computer can assist me in finessing that part to make it sound more solid, more in time, more whatever. There’s no mystery, a lot of singers will use Auto-Tune now to get their pitch more exact. The reason they’ll do that is there’s lots of singers who can’t sing at all but you do have a few singers, obviously, who are talented, they’re trained, they practice their craft. If they go for a performance and convey the right emotion and have all that wonderful once in a lifetime charm, the last thing you want to do, believe me, is redo it, try to recapture all that charm just to correct a few notes, pitches. If you can nudge those note pitches with some software, you can do it and not losing any of the charm. There’s huge advantages.

I’m not so analog righteous. I’m not militant about any of it. Whatever gets you to the finish line. At the end of the day if you write a good song and you have very good performance, execute it, period.

Focusing on the word ‘performance’, was it important to you to have the live tracks as well as the demos on the reissues in order to show the full scope of the band, showing that you can do it live as well as in the studio?

It’s not so important to me. I know growing up, as a fan of my favorite bands, I enjoyed hearing demos. I enjoyed hearing the live thing. It humanized the group more, and as a musical architect learning to do these things, I love hearing how the ideas evolved. That’s endlessly fascinating to me as a fellow musician, arranger and creator.

Those hardcore fans, of which those are the ones that are out there 20 years later, that is legitimately fascinating to them. And it gives me great joy to be able to share that with them. A lot of my heroes, when they made demos, they had such poor equipment to work on, the demos sound atrocious. It’s very hard to hear anything. We were at least able to record on some pretty decent gear back then in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s. So, it’s fun to share those ideas.

No Comments comments associated with this post