I did not know Bruce Hampton as well as his family, friends, and peers knew him. If truth be told, I hadn’t seen Bruce in over 15 years. Nevertheless, the time we spent together left a permanent impression on me. Respectfully, I’d like to share some of those stories in honor of all that I learned from the Colonel.

I was a fan before I met him. I wore out the live album, Col. Bruce Hampton and the Aquarium Rescue Unit, playing it daily in my college dorm room. I loved every second; from Apt. Q 258’s machine-gun drumming that underscored John Bell’s freewheeling intro all the way to the last wonderful note.

I loved that the record was on the revived Capricorn label, once the first home of one of my favorites, The Allman Brothers Band. And that Bruce was a self-professed retired colonel that played Chazoid (?!), and sounded like a rising, cosmic dervish, hybrid of Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart. And that every musician in the band was astonishingly, repeatedly, “how-do-they-do-that?” good.

Part of me wanted to keep it to myself—my secret treasure—just as a part of me wanted everyone I knew to hear them.

In May of 1993, I was a 20-year-old junior at Syracuse University and in a band. Bruce and the ARU played on the 6th of that month at a club in Syracuse called the Pump House. We were the opening group.

After the Unit did their soundcheck, most of the guys returned to their touring vehicle—a converted airport shuttle—while Bruce sat at the bar. He wasn’t drinking, just sitting, while we set-up. We did a quick test-run, and after, I walked over to Bruce, introduced myself, and asked him what is the secret.

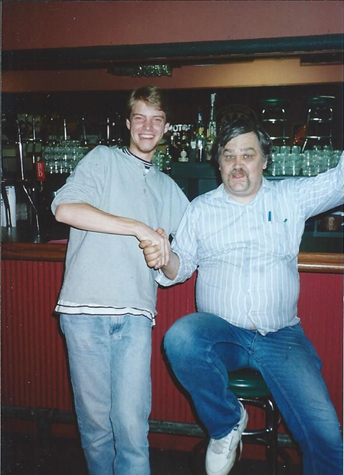

A bandmate of mine came over and asked to take our photo. Just before the shot, Bruce grabbed my hand, threw up his arm, and said, “Signing the big deal!” He was joking.

“If you want to be a musician, you have to work. You have to go in a room, every day, and play eight hours a day,” he said. He wasn’t joking.

At the core of that exchange is something that has been echoed by everyone that knew him; something Bruce often articulated, himself: Take the music seriously. Don’t take yourself seriously.

A few years later Bruce played at Club Babyhead in Providence, Rhode Island. He had left the Aquarium Rescue Unit and formed a new duo, with Dr. Dan Matrazzo, called the Fiji Mariners. I went up early to the soundcheck to say hello and ask if, maybe, I could sit-in for a song.

“I have to tell you, no, and I’ll tell you why,” said Bruce. “The only person we let sit-in without rehearsing is Derek Trucks.”

He did accept my offer for dinner, and over a messy pile of babybacks, the waitress gave Bruce a T-shirt, compliments of the restaurant. He put it on immediately. It was easily, ridiculously a size much-too-small, stretching every last fiber to its breaking point. Bruce wore it, gratefully, the rest of the night.

We got back to the club, and an old friend of Bruce’s had arrived from Boston, unexpected and carrying a guitar. He asked Bruce if he could sit-in. Bruce sighed at the predicament, then turned to me with a smile, and said, “I guess you’re playing with us tonight, too.”

After the show, I introduced Bruce to a buddy of mine. What happened next, we’d both be happy to verify in any court.

They shook hands, and Bruce said, “February 11.”

My friend, stunned, spit out, “That’s my birthday.”

“I know,” said Bruce.

No Comments comments associated with this post