Berkfest: The Little Festival That Could(n’t)

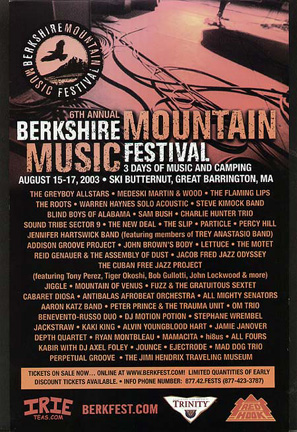

Poster from the final year

The December 2002 Relix cover story singled out the year’s musical superlatives. In the festival realm, Relix named the inaugural Bonnaroo as the top large-scale event, while the honors in the small-fest category went to the fifth annual Berkshire Mountain Music Festival. More than a decade later, Bonnaroo remains a steady, significant presence in the festival scene, while Berkfest never made it past 2003. Why not? What happened to the event that had built a steady following on a bucolic site in the mountains of Western Massachusetts? The answer says something about the nature of the concert industry during that era and also serves as a cautionary tale for other would-be promoters with festival dreams.

The driving force behind Berkfest was Andrew Stahl, who was still a Northeastern University student when he opened Gamelan Productions in 1992 to book a few of his friends’ bands. By early 1998, he had expanded his efforts and was well-established in the Boston area as a promoter, bringing in such groups as The String Cheese Incident, moe., Galactic and Strangefolk just as the jamband scene was rapidly increasing in popularity.

A college friend suggested that Stahl take the next step and create a music festival. While the promoter initially balked due to his inexperience, String Cheese Incident manager Mike Luba soon introduced him to High Sierra Music Festival co-founder Roy Carter, who pledged that if Stahl could find a site, then High Sierra would support his efforts. Stahl eventually identified a location and launched the Berkshire Mountain Music Festival to much anticipation—and three steady days of rain—at Steele’s Farm in Lanesboro, Mass., from June 12-14, 1998. The lineup included Los Lobos, The String

Cheese Incident, the funky Meters and the Greyboy Allstars Sidecar Project featuring Karl Denson (a group soon to be renamed Karl Denson’s Tiny Universe). Just over 1,000 folks braved the weather for an event that mostly took place in auxiliary tents, other than one fortuitous dry moment when

Los Lobos took the stage. (Los Lobos also provided Stahl with another highlight from the weekend: He drove the band members across a muddy field in his SUV for their set and they encouraged him to take a detour and pull donuts…twice.)

While the event dubbed Mudfest lost money, all the parties agreed to give it another go. However, an alternative site became necessary.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t do it there anymore,” Stahl reflects, “because a school bus full of hippies got stuck in the mud. Robbie Steele pulled them out and then they drove their bus back into the same spot and got stuck again. When they knocked on his door, he grabbed a shovel, threw it out to them and said, ‘Get yourselves out.’ Well, they couldn’t do it and started knocking on everybody’s door in the neighborhood. They were filthy and muddy and they ended up knocking on the mayor’s door while somebody was urinating in his bushes, and that was the end of Berkfest in Lanesboro.”

The festival relocated to the Butternut Ski Basin in Great Barrington, Mass., where it remained for the next five years, offering music on four stages as well as two late night lodges. Headliners included: The Roots, Soul Coughing and an all-star jam with John Scofield, Oteil Burbridge, Bob Moses, Nate Wilson and others (1999); Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, Medeski Martin & Wood and The String Cheese Incident (2000); moe, Soulive and The Word (2001); Steve Kimock Band, Sound Tribe Sector 9 and Michael Franti & Spearhead (2002); and The Flaming Lips, Warren Haynes solo acoustic and Greyboy Allstars (2003).

The audiences increased during those first few years at Butternut, although in 2000, the seemingly inevitable torrential rain, coupled with caravans of touring SCI fans, led to complications and ultimately a free fest.

“That was the year of the famous traffic jam,” Stahl remembers with a laugh.” My grandma was watching the news in Queens, N.Y., and traffic was snarled all the way from New York and she called me to leave a message on my answering machine: ‘Was that you who caused the traffic jam?’ The state police almost arrested me and said, ‘If you don’t turn this into a free show you’re coming down with us.’ So we had to close our box office down. Still, at the end of the festival, a lot of people still paid us and said, ‘It was miserable getting here but it was incredible.’”

Despite the police mandate, Berkfest turned a profit for the first time in 2000 and continued to make modest gains over the subsequent two years. Beyond the Relix laurels, many festivalgoers identified the fest as a favorite, enamored of the intimacy and the programming (assisted by infrastructure improvements in the fourth year when Stahl enlisted Phish’s longtime head of security John Langenstein to reconfigure the layout).

Yet despite this momentum, 2003 marked the final year of Berkfest. The festival’s demise ultimately turned on two considerations. The first of these was capital. In July, Stahl debuted the Mid-Atlantic Music Experience in Lewisburg, W.Va., with Widespread Panic, moe., MMW and a few dozen other acts. Notwithstanding an appealing lineup, Stahl’s first major event outside of his home market drew only 4,500 of the 10,000 people he needed to break even, and his loss exceeded $650,000. Berkfest also fell back into the red that year and he lost an additional $125,000.

“I was competing against Clear Channel, which is now Live Nation, buying everything under the sun,” Stahl explains. “That summer, they were dumping tickets to shows at [the nearby] Great Woods to own the market and put people out of business.”

Another pressure weighed down on him as well. “An equally large part of it was that the drug scene had gotten out of hand and, for me, it was not about the party, it was about the music,” he said. “From the tree line forward, I thought Berkfest was one of the greatest musical events, but from the tree line back, while it had its moments of fun, it was scary for me. I was responsible for bringing these people here and they were doing really crazy things.

“So I just cut my losses. Even if I kept it going, how long was it going to last? Clear Channel wasn’t going to get any smaller, and I was starting to think that the only way to succeed in the industry was to be someone I didn’t want to be. I started not liking music anymore, which was killing my soul.”

Stahl relocated to Southern California where he became a stand-up comedy promoter, utilizing the same skill set he developed at Gamelan. Four years later, he decided to leave that business behind and is now a location scout, working on film, television and commercial shoots. He now intends to launch a tribute site at Berkfest.com.

“The biggest thing back then was I didn’t love music anymore and that really hurt me,” he says. “It had always been an important part of my life. I needed to love music again and since I don’t have to work in the industry anymore, now I do.”