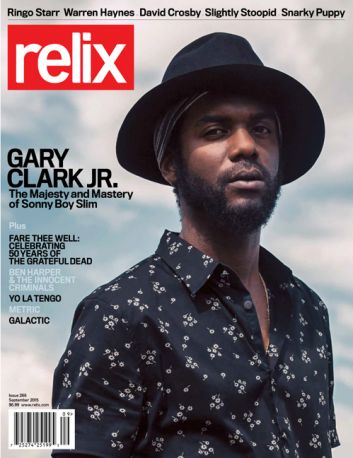

Gary Clark Jr.: Searching for Sonny Boy Slim

The September issue of Relix features a cover story on Gary Clark Jr. Here’s an extended excerpt from the article, which explores Clark’s latest album, The Story of Sonny Boy Slim and much much, much more.

Although his name might not strike a chord, Sonny Boy Slim has garnered surging acclaim ever since he first began gigging in his hometown of Austin, Texas as a teenager. He originally aspired to be a vocalist but proved to be a quick study on the guitar and built from a blues lexicon that complemented his soulful singing. In 2001, while still a high-school student, his prowess led Austin mayor Kirk Watson to proclaim a day in his honor. Over the ensuing decade, his career maintained a steady upward arc as he earned plaudits for his fiery live performances and emerging songcraft and, then, for his acting debut as a 1950s Southern itinerant musician, appearing on-screen alongside several Hollywood heavyweights. His trajectory exploded in 2010, following an invitation to perform at Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival and the inking of a record deal with Warner Bros. Records.

Sonny Boy Slim is Gary Clark Jr. It is the moniker he fashioned for himself, drawing on the nickname his mother gave him and the tag that others have supplied due to his lanky size. Nearly three years after the release of his last studio effort, Blak And Blu, Clark is back with The Story of Sonny Boy Slim. The record’s sweeping autobiographical title and poignant, expressive performances suggest that it offers something of a personal testimonial.

This point is reinforced by the fact that rather than using his stellar live band, he played most of the instruments himself. In addition, while he recorded Blak And Blu in Los Angeles, Clark ensconced himself back home in Austin to develop and capture the material on The Story of Sonny Boy Slim. He worked at Arlyn Studios in Texas, producing the record along with his front-of-house soundman Bharath “Cheex” Ramanath and Jacob Sciba, the chief engineer at Arlyn.

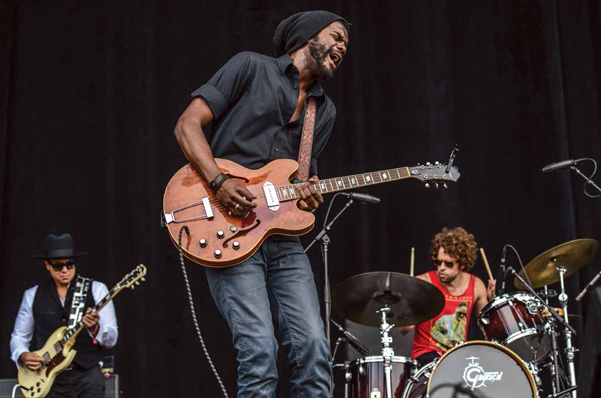

Shortly after returning from a European tour and much heralded appearances at Bonnaroo and Lollapalooza, Clark—a recent first-time father with partner Nicole Trunfio—took time to reflect on his Austin origins and ongoing progression. Here, Clark shares the story of The Story of Sonny Boy Slim.

You’ve been at this for a while and people have discovered you at various points along the way. I first saw you in the 2007 John Sayles film Honeydripper, which led me to seek out your music. Can you talk about how you came to appear in that film? Was acting something you had aspired to do?

I was hanging around Austin, and Louis Black, the guy who puts on South By Southwest and [co-founded] The Austin Chronicle, knows John Sayles, who wrote and directed the film. John reached out and asked if there was a young black dude who played guitar and could maybe act a little bit. So, Louis Black brought my name up, and John Sayles and his partner/producer Maggie Renzi came down to Austin during one of my showcases at SXSW. They approached me out back and asked me if I wanted to audition for this film.

The next day, I went over to this house and did a quick little run through a couple pages of the script. I thought it went terrible, but they asked me if I wanted to be a part of it. A little while later, I was on set in Greenville, Ala., in wardrobe getting my hair cut. It wasn’t something I had ever really thought of for myself but I figured, “Why not? It’s not every day someone asks you to be the lead in a movie.”

Did you take anything away from that experience that you ultimately applied to your musical career? Perhaps as it relates to finding yourself in new settings working with renowned musicians like Eric Clapton or The Rolling Stones?

It’s funny. The first day I was on set, I was really nervous and they could tell. It showed on screen. I had never done this before—I was a fish out of water. And there was an actor on the set, Brent Jennings, who pulled me aside and taught me some things. He had me do this drill—I guess it’s an acting exercise—where he said, “I’m going to start walking and I’m going to keep walking until you convince me that I’m about to fall off a cliff.” So, I’m screaming, “Hey! Hey! Hey!” and finally, I go, “HEY!” Then he stopped and he told me, “That’s it. You gotta let go. You gotta be completely in that moment. You have to step outside your comfort zone and not look at yourself as being an actor, but being a real part of the situation.” And that’s something I carry with me, as far as letting go and letting loose. It’s very valuable, so I’m thankful to Brent Jennings.

Another one was when I met Danny Glover and Charles S. Dutton. I came around the corner, and they stared me up and down. I think they were kind of testing me to see if I was shaken by it. They didn’t say anything for a while. And I was just like, “Uhhhhhh, ummmm, soooooo, hey, guys.” They busted out laughing like, “Hey, man, we’re just busting your balls—just checking in the new guy.” I learned to be confident—I learned to be aware of what was going on, and make the most of it.

When you play a show, do you get nervous before you hit the stage? Maybe when you’re in a new setting or sitting in with other artists?

No, I don’t get nervous. The thing I don’t like, though, is the sitting around before showtime. I start to think a little bit too much. I’m just ready to get up and do it because that’s what I’m there to do.

When you were growing up, did you take particular inspiration from filmmakers, novelists or any artists other than musicians?

Definitely. I remember being introduced to the poetry of Langston Hughes when I was a kid—somebody who looked like me, who was expressing himself about what he saw around him. It helped me take a step back

and be more aware, and be able to write. Cadence and rhyme—those were kind of my first interests in writing. What I’ve taken from that is a style of writing music. I think of it as simple poetry.

I also loved art when I was a kid—painting, drawing all over things. I was always trying to express myself in that way. Art, poetry and music were the things that really drove me and inspired me. Those were the things I was drawn to.

As far as performing and live music, I was also influenced by my first shows, which were field trips in elementary school to go see a symphony. I remember being blown away by that, just how many pieces were working together to make these beautiful sounds.

At that point, had you picked up the guitar yet?

No. I was just a shy kid in school who liked to sing, but I was too shy to sing in front of anybody. But those were the moments that stood out, and I said to myself, “Man, I love this. This is something I’m interested in.”

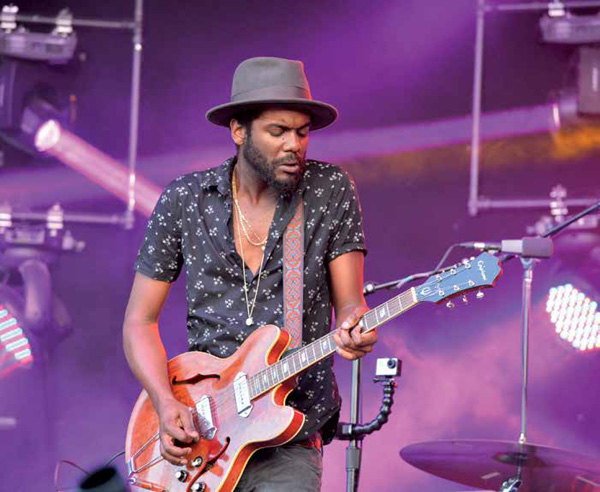

photo by Stuart Levine

Have you ever considered performing with a symphony?

Yeah, I have actually. I love the sound of old soul and those big arrangements. I think it would be beautiful to incorporate that instrumentation into what I do. That’s some of the stuff that connected with me—the idea that the same strings playing Beethoven were playing over Motown records. It all gave me the same feeling. I don’t know if I’d ever play classical guitar with a full symphony, but I’ve heard of some rappers doing it—Bun B in Houston

rapping with a symphony. I did a Beatles tribute in Austin with Will Taylor and Strings Attached, which I thought was really beautiful. So yeah, I’m up for that.

After your experience at the symphony, can you point to another show from that period in your life that you attended as a fan that really left its mark?

One of the first shows I saw early on was Jimmie Vaughan and the Tilt-A-Whirl Band. He just released the record Out There [1998]. I was 14, and he was playing a little spot in Austin called La Zona Rosa. I remember being really excited about that. George Rains on the shuffle—I loved the way he played. I loved the way his whole band sounded. Of course, Jimmie Vaughan was as cool as can be. I had never really heard a sound like that—blues, swing, lowdown stuff with a big band, piano, horn section, backup singers. I was inspired after seeing that show. It made me want to get up there and be a part of it. To this day, I remember he looked at me, and he even kind of smiled and pointed. I was like “Oh, my God!” Superfan-ing out.

Thinking back to your childhood, people often ask you about Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan, but you also drew from many other sources, such as Nirvana.

Yeah, Nirvana definitely inspired me. I learned how to play power chords by listening to them. I learned what a distortion pedal was. I learned what a chorus pedal was. I came from the blues/ R&B world, where it was pretty clean tones, maybe a wah-wah pedal here and there. But, that was my introduction to expanding my range on what you could do with a guitar, and the sounds that you can make. As a 12-or-13-year-old kid, the power and intensity of distortion and fuzz opened my eyes.

As you look back now, nearly 20 years later, is there someone else that you can identify as an inspiration—maybe who you didn’t fully appreciate at the time?

We just did some shows with Lenny Kravitz over in Italy. I didn’t realize how many of his songs I knew the words to. I remember hearing his music and seeing an image of him as a black boy with a guitar. I thought that was really cool. That gave me confidence.

I also did some shows with Carlos Santana. My dad—when I first started playing guitar—popped a Santana album in front of my face and said, “You gotta listen to this.” I remember listening to Jonny Lang—young guy, made it seem possible. Kenny Wayne Shepherd. Are you talking about strictly guitar players?

I was about to ask you about singers.

Stevie Wonder, absolutely. Another one of the first CDs I bought was a Blackstreet record. I loved R&B. I loved SWV. I loved No Doubt—I thought Gwen Stefani had a great voice. I really liked Usher; his My Way record had a lot of acoustic guitar on it. So, as I learned to play guitar, I appreciated his voice. When I started out, I really thought I was just going to be a singer, an R&B singer, and maybe have a group because I love vocal harmonies.

How did that transition take place? Was there a moment when you decided to supplement your voice with a guitar?

I did this talent show in the 7th grade with my buddy Robbie. We called ourselves Young Soul, and he wrote this song, “Young Soul,” but his family ended up moving to France. The only person that I knew who was musical in that way, was Eve Monsees because she was in the talent show as well. Robbie and I ended up beating them in the talent show. Then, the next year, I started hanging out with Eve, and she was playing guitar. So, I was just naturally influenced to pick up a guitar as well. She was doing both, and I was like, “Well, I want to do both” because it seemed like another extension of her voice. Maybe if Robbie hadn’t left, I might have been in a boy band or something. We might have taken *NSYNC’s spot. [Laughs.]

photo by Dean Budnick

You just returned from Europe. There’s a particularly strong market for traditional American blues over there. While that’s not what you do, did gigging in Europe push you to explore that side of your music?

Overseas, people really want to hear the roots. People will yell, “Play some blues, Gary.” That kind of takes me back a little bit. I’ve had friends who’ve gone over and lived in France, Germany, Belgium because people appreciate playing the rootsy, really low-down stuff. It’s not mixed with anything. It’s just straight-ahead. There’s a little bit of that expectation, so we’ll give them some to make them happy. At the same time, I do what I do.

Was there any obligation or pressure to maintain that tradition, or bring it forward, or is that something you can’t worry about?

It used to worry me, but I can’t really do that because I can’t do what Muddy Waters did. I can’t repeat those records. They’re classics for a reason. They’re a foundation for a reason. Of course, blues is my foundation, but I didn’t come up in those times. It’s not the same era. I’m surrounded by all types of different influences, different people and different music. So, I just try to stay true to that, instead of doing what people expect me to do. At the end of the day, I want to be me, and not what people expect me to be.

Do you think that musicians carry a particular social responsibility since they have a platform for expression?

As both a listener and performer, I want to hear things that move me, and make me think and try and progress and grow and be better. I listen to Marvin Gaye, “What’s Going On,” and it makes me wonder about the state of the people and the world, and what’s going to happen. I’ve got a child now, so I’m even more conscious and aware of that.

Don’t get me wrong, I like to shake it up too, and let loose—just throw my drink up in the air, and bob my head a little bit. I love that. Or go to a show and see people pushing each other around in the mosh pit. But when I listened to music as a kid, it would change my life. It influenced me heavily. It’s good to be aware. I think the microphone is powerful and you can use it how you want to; it’s a form of expression. I love to hear soul music, and it’s music that touches the emotions.

This seems like a fine segue to your new album, The Story of Sonny Boy Slim. Did you backlog songs on the road and then record them or did you develop them in the studio? How did the compositions themselves come about?

This process was a hot mess. I bought an MPC because I thought I could travel with it and make rhythms and drum beats—basically the skeleton of a song using a drum-programming machine. I was on that a lot at first, but then I was distracted on the road and couldn’t really focus. The MPC got dusty sitting in the back of the bus.

So, then I got off the road, and I would basically just go into the studio, and set up drums, bass, guitar and keys, and make sure all the mics were on. I would jump on each instrument and put down an idea, whether it was piano first, drums first, guitars first or just singing something. There was no order to this thing at all. I would build that slowly. I went into Arlyn Studios and, for two weeks, I just banged out 19-20 ideas and got a CD.

Then, I came back to the house, where I had a little pre-production studio set up. I would shut the door, turn off my phone and tell my girl, “I love you, but please don’t bother me right now.” I tried to build from there, adding things and taking them away, and trying to develop the idea. I would go back in the studio with the proper gear and the right people turning the knobs, and develop things more.

It just got to a point where everything was on the rig at Arlyn. I spent a lot of time just listening and building there, and figuring out what worked best—the drum sound, bass sound, guitar tones and arrangements. I re-did a lot of things. Some of it, we just went in and one-taked it. I did this song called “Shake” with [Fabulous Thunderbirds drummer] Jay Moeller, where I had this little Quaker Oats can guitar thing. I called him up and

said, “I have this idea you’d be perfect on, can you come out to Arlyn and do a take?” I couldn’t even begin to explain the process. The thing was just me throwing paint at the walls. I pushed myself to the limit, and it helped having the guys in the studio be brutally honest, and tell me, “No, that sucks” or “That’s cool.”

Has it been harder to find people who are willing to share a negative opinion with you nowadays?

There are not a lot of people who will do that. But I would have to say my boy Choppy Cheex is brutally honest, by nature, anyway. I trusted him. He’s not one of those dudes who will say, “Oh, that was great,” if it was terrible, or say, “Your voice sounded great,” if it wasn’t. He’ll just straight tell you, “Your shoes are wack.” I needed that.

Why did you decide to record most of the tracks yourself, rather than bringing in your touring band?

I wanted to push myself as an artist, musician and singer. I had been out on the road, playing the same songs and the same set, and not really practicing as much as I should have been, or would like to. So, I needed time to just ‘shed, and in that process, capture the ideas and the moments of me searching and experimenting. It really was a process of wanting to become better—and the time to do it was in the studio—and work it out that way. I wanted to be free to do it, and have the time to do it, as well. I just needed this for myself to get things out. Sometimes, I’ll just sit back in the studio and reflect. A lot of things have happened very quickly—a lot of changes in my life and I haven’t really had time to process them. I spent a lot of time in the studio reflecting, putting out ideas as they came to me. It was like my self-therapy. I needed to vent and find myself, find my voice, do what I wanted to do, go in the direction I wanted to go—as a musician, as a man.

To read more, pick up the latest issue of Relix.