Deadicated: David Browne Charts _So Many Roads_

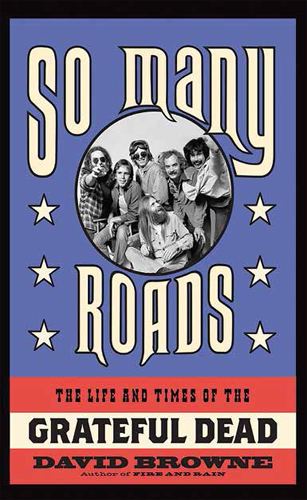

Over the course of a journalism career that began in the mid-‘80s and has included stints at the New York Daily News, Entertainment Weekly and Rolling Stone, David Browne has utilized the – form to explore the lives of such performers as Jeff and Tim Buckley [2001’s Dream Brother], Sonic Youth [2008’s Goodbye 20th Century] and The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young [2011’s Fire And Rain]. Browne’s most recent work is So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead (2015), which places a focus on individual days in the group’s career as a means to examine the Dead’s history and cultural impact.

You’ve written quite a bit about the Grateful Dead, particularly over the past few years, but what led you to commit to such an exhaustive project?

In a way, it was a spinoff of my last book, Fire And Rain, which was all about 1970. I really enjoyed writing that book and writing about that era and that music. There was a little part of me that thought, “You know, it might be fun to kind of stay in this same zone for my next book,” which I’d never done before.

With Fire And Rain, I got to write about the first records and bands I ever got into, and that was a lot of fun because I’d never written that much about Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young before. And the Dead were another band I got into during that same period. I wondered what I could do. So I pulled out my copy of Dennis McNally’s book [A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead] and Blair Jackson’s book [Garcia: An American Life], and I asked myself, “What in the world could I bring to this?” Then after mulling it over and reaching out to some people, I thought, “Well, perhaps I could bring a bit of an outsider’s angle to it.”

Structurally, I’ve always approached my books—since the first one on Jeff and Tim Buckley—almost as if they were novels. I like to do the research and reporting and then tell the story with characters and settings and scenes, and give it as much of a “you-were-there” feeling as possible. I felt maybe that’s something I could bring to the Dead story because if there’s any scene in rock history that’s been full of colorful characters and interesting settings, then it’s the world of the Dead.

I should also mention my wife [Maggie Murphy], who is an editor. When I told her back in 2011 that I was considering a book on the Dead, and that if I finished it in time it could come out around their 50th anniversary, she said, “Oh, 50th anniversary—you should do 50 days with the Dead.” My first thought was “Wow, that’s an interesting idea.” My second thought was, “Oh, my god. I can’t write 50 chapters. That’s mind-boggling.” [Laughs]. But that concept stayed in my mind, and that merged with my other ideas, too. I thought, “What if I structured it that way?”

I’ll also say that I’m a big fan of micro-histories. I love books and movies that just focus on a little sliver of time, whether it’s a movie like Selma or [Thurston Clarke’s] wonderful book on Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign, The Last Campaign, which is all about Bobby Kennedy in 1968. I love those kinds of projects that really delve deep into a historical moment and make that symbolic or representative of a bigger story. And I thought, “Maybe I could do a series of microhistories of the Dead, and maybe that would be a lot of fun to do.”

That was also a guiding principle with this approach—if I structured it that way, it would be a ton of work, but it could be interesting, too.

Can you talk about your thought process and the challenges you encountered in applying that particular approach.

At the very beginning of the project, before I even knew I was structuring it this way, I created a Word document with a chronology. As I read through all the other books and old articles, I just threw any dates that were interesting into this chronology—birth dates, death dates, concerts, recording sessions, anything. If there was an exact date, then I put it down. And by the end, this became a pretty long document. It was 20 or 30 pages when I printed it out. When I was interviewing Trixie Garcia, I pulled it out to check some dates and ask her about some things—I always brought a copy of this printout with me to jog my memory and other people’s memories—and Trixie looked at it and said, “Oh, what’s that?” I explained, and she asked, “Oh can I see that?” So she flipped through it, going, “Oh, I didn’t know this. I didn’t know that. You should just publish this.” That was nice to hear.

Once I had the chronology, there was the question of which days I would have enough information on to track the day and also weave in backstories, and which days would be representative of a particular era. That would allow me to go a little bit backward and a little bit forward in time.

Jerry’s death was obviously a huge day, but I also felt like so much has been written about that. I thought there would be maybe a better way to go about that. That’s why I thought the Deer Creek show was, to me, more symbolic of what had happened to the Dead as a group by that point, as opposed to what just happened to Jerry. It seemed to represent the things they were grappling with—crowd control and the changes in their audience tied in with Jerry’s issues. It was all so encapsulated that night. I thought that spoke more of that period than just the day Jerry died because I did want this to be a book about the Dead and not just Jerry. Jerry’s story can easily overwhelm this whole saga. I tried to make sure it wasn’t just about that. There are other guys in the band and other issues to deal with.

For example, the “Touch Of Grey” video shoot. Some people might go, “Come on, in the history of the Dead, was them making a video that important?” But again, to me, that was such an interesting day. First of all, it was a positive day. They were in such a good space at that point in time—just the fact that they agreed to lip sync a song for hours onstage, despite the fact that they bristled at any industry rules and conventions up to that point. And, of course, there was all this interesting backstage stuff going on with the crew that day that I thought captured that other aspect of their organization. And that day, that video, combined with the song, really was a game-changer for them—even though, at the time, nobody knew to what extent it would be. But it was because that video, as we all know, was on MTV constantly, and the song was on the radio, and that really took them to some other level. So to me, that was such a multi-faceted moment in their career, and I had enough information to put together the whole day. So I thought that would be perhaps a less predictable one, but hopefully, it would make sense when people read it and that would be a valid choice.

Do you see any particular through lines that span your books?

I tend to be attracted to stories about people who get into doing something because they love to do it and how something that’s natural and grassroots then grows. What happens when that thing that you do suddenly becomes much more successful than you thought? How do you grapple with issues of integrity and being true to yourself? I think that’s really true of Jeff Buckley, who started singing at this little tiny club in the East Village and, suddenly, he signs with Sony Music and becomes the flavor of the month. It was true of the skateboarders who I wrote about in a book on extreme sports that I did back about 10 years ago [Amped: How Big Air, Big Dollars, and a New Generation Took Sports to the Extreme], who suddenly find themselves being approached by Mountain Dew once the X Games start—how they deal with mainstream acceptance. It was true of Sonic Youth, who were signed by Geffen Records and went from the indie world to the major label world, and being on Lollapalooza tours and grappling with that kind of level of success and compromise.

I think that’s true of the Dead story, too. These are guys that got together—a motley crew of guys with very little in common and, in some ways, just started creating a new kind of music from all these disparate elements with no super commercial expectations in the beginning—modest ones, at best. Then, as we see, once that train got on the tracks, it kept going, and by the ‘80s, of course, they were huge and popular and dealing with fame and celebrity and business pressures, and still trying to be true to themselves and grappling with that.

What surprised you the most during your research?

I think what certainly surprised me, in the bigger picture, was the often-brutal intensity of the entire scene. When we think of the Dead, certainly one of the iconic images we all picture is that back cover of Aoxomoxoa. They’re sitting there, all the band and most of their friends, and it’s just got this sort of communal, sunshine daydream vibe to it. And that was an aspect of their story, but one of the things you learn is that they had a pretty badass organization, almost from day one. I mean, those guys could be really tough on each other and hard on each other. The organization had a certain “survival-of-the-fittest” vibe, which people like Brent Mydland and Keith Godchaux got caught up in in the worst ways. It was a pretty rough and tumble place to be. After shows, going back to the late ‘60s, they would gather in hotel rooms and listen back to tapes of that night—often that Owsley taped in the early days—and dissect everything and be very brutal with each other and criticize each other. And I thought, “Wow, it was not all hugs and slaps on the back.”

Learning about all the different dynamics within the band was interesting—who was getting along with whom at what point, and who wasn’t getting along with whom. To listen to that tape of the band meeting in August 1968 when they tried to fire Weir and Pigpen, sort of—it’s still vague—and to actually listen to that tape in the Grateful Dead archives and hear that degree of confrontation and some degree of turmoil was really eye-opening to me.

In So Many Roads, you emphasize that it’s hard to draw any definitive conclusion, even after listening to the tape.

It’s a strange thing because, when the meeting starts, you hear Phil, Jerry and Rock Scully being pretty openly critical of Bob and Pigpen and saying, basically, “You’re not on our wavelength, and something’s not happening here.” But by the end of the meeting, they’ve sort of pulled back a bit. And I did ask Phil Lesh about that because I don’t think he mentioned that in his book. And he said, “Well, we didn’t want to fire them, it was just almost like a warning. It was just us saying we might go off and do this thing with just the four of us.” So the relationships and the way they dealt with them was, at one point, very basic—it was like they were always stuck in this kind of perpetual adolescence in some ways—and yet it was also very complicated at the same time. So just trying to untangle those dynamics was a challenge.

Public perception of the Grateful Dead shifted quite a bit during your career. What do you think accounts for that?

I remember the first time I wrote about the Dead in 1987. Someone called me up—I won’t name any publication—and asked, “How do you feel about the Dead?” I said, “Well, I grew up with those records, why?” And they responded, “Well, I’m trying to find someone to review this new album—someone who doesn’t hate the fact that they exist.” I thought, “I don’t hate the fact that they exist.” But that was pretty typical for that period of time. Granted, the first half of the ‘80s wasn’t their greatest era, so I kind of understood that to some degree.

Right now, it’s easy to look at the Dead and see them in a different light as a group that really was true to itself and really seemed authentic, and seemed uncompromising. Though they had a few moments where they compromised, like when they worked with Gary Lyons on Go To Heaven—or people might point to Jerry’s ties as him selling out or something. But in general, the vibe around them was that they made music on their terms when they wanted to make it, and they had this fanbase that was with them through thick and thin. It didn’t matter if they had a new album or not, whether the album was any good—fans still flocked to see them. They didn’t have to sell their songs to commercials or video games. They could go years without a new album and still be successful. People look at that now, at the whole big picture, and think, “Oh, my god, somebody actually got away with all that?” And I can see young bands thinking, “Why can’t we do that?” [Laughs.]