The Other Side: Brent Mydland’s Unreleased Solo Album

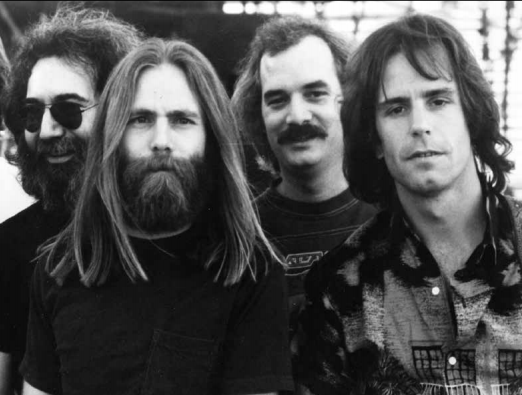

The year 2015 not only marks a half-century of the Grateful Dead, but also the 25th anniversary of a more somber occasion. On July 26, 1990, the group’s keyboard player, Brent Mydland, succumbed to a lethal combination of heroin and cocaine at age 37. Mydland had joined the Grateful Dead in 1979, following a stint in the Bob Weir Band. Mydland became a member of the Dead after Keith and Donna Godchaux departed the group, and he would come to assume both of their roles, filling the keyboard space with the thick sounds of his Hammond B3 and sweetening some of the ragged vocals with his high harmonies.

Bob Weir has described Mydland’s final years with the group, captured in two box sets, Spring 1990 and Spring 1990 (The Other One), as the Grateful Dead’s “hottest era.” In his autobiography, Bill Kreutzmann adds, “Brent played the best organ I’ve ever heard anybody play. He had the piss and the vinegar in him and he brought it to the table every night. The band, as a whole, had come alive again. Those [spring ‘90] shows had energy, with thunderbolts of electricity to spare.”

Beyond his efforts on keys and vocals, Mydland also contributed original compositions to the group, increasingly finding a style that suited the band. While early offerings like “Far From Me” and “Easy to Love You” sounded a bit too reminiscent of the era’s radio-friendly fodder to suit many Deadheads’ tastes, his later tunes, including Built To Last’s “Blow Away” and “Just a Little Light” became well-regarded live staples.

But there are four boxes of tapes that currently reside in the Grateful Dead vault, which attest to another side of his creative output. Labeled “Brent Solo Project,” they reflect an intensive undertaking at the Dead’s Front Street Studio in San Rafael, Calif., over a period from 1982 to 1983. Betty Cantor-Jackson, the group’s longtime recording engineer with whom Mydland was involved in a romantic relationship, produced the sessions. The band’s John Cutler also stepped in to engineer.

“Brent and I were living together at the time, and he had material he wanted to record,” Cantor-Jackson recalls. “I told him I would make time, in the Front Street schedule, but first, he needed to put a band together. He didn’t want a Grateful Dead album.”

Without a working solo band of his own, Mydland began scouring the area to assemble players for the sessions. One night, he and Cantor-Jackson scouted the local group Billy Satellite, which featured two guitarists—one of whom, Danny Chauncey, would join .38 Special a few years later. Cantor-Jackson says that while she thought Chauncey was the man for the job, Mydland preferred Monty Byrom, the group’s less flashy player.

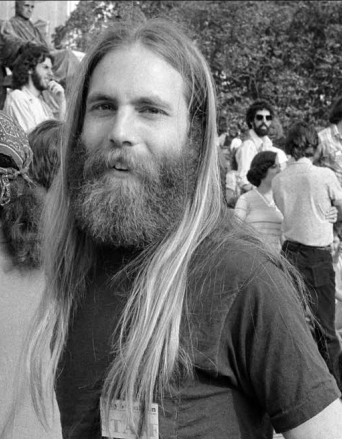

“It was one of those crazy Alice in Wonderland kind of things,” Byrom remembers. “We were just getting signed to Capitol at the time, and Brent and Betty were sitting in the audience one night. I’ll be honest: I didn’t know who Brent Mydland was. I wasn’t up on the current Grateful Dead lineup. So, I got a phone call at rehearsal the next day and this guy said, ‘I’m Brent Mydland from the Grateful Dead. I really like your guitar playing and I was wondering if you’d like to play on my record.’ Within a week, he was at our rehearsals hanging out, jamming with my band—and we just hit it off immediately. I would consider him my best friend at that time. I moved into Betty’s house for a while when we started these crazy rehearsals, and I found myself sleeping in a bed underneath naked pictures of Janis Joplin.

“Brent was one of the most talented guys I’ve ever met. I’ve never seen anybody that could sing with those kind of notes, night after night. He was a cross between Gregg Allman and Howlin’ Wolf. It was crazy. And that was my introduction to the music business.”

Drummer John Mauceri and bassist Paul Marshall completed the project’s lineup. Both musicians had deep ties to the California psychedelicrock world. Mydland had met Mauceri in 1974 when they backed the folk-rock duo Batdorf & Rodney. Four years later, Mauceri recommended Mydland to Bob Weir when Weir assembled a quintet to tour in support of Heaven Help the Fool. Marshall, a member of the LA-based Strawberry Alarm Clock from 1969-1971, had also previously performed with Mauceri, who suggested his participation to Mydland.

Although Mydland didn’t want it to become a Grateful Dead album, given his role in the group, and the locale of the recording, various members would check in on occasion. Cantor-Jackson recollects that Jerry Garcia appeared on one of the tracks. While the music that has surfaced thus far doesn’t bear this out, there are plenty more tapes currently sitting in the vault. She also says that longtime Jerry Garcia Band bassist John Kahn contributed to one song.

Byrom and Marshall both place Mickey Hart and Phil Lesh at various sessions as observers. Byrom recalls one moment while working on the song “Maybe You Know”—“I remember vividly, while playing this solo, looking across the studio and Phil Lesh was jumping around losing his mind on this song. He was just giving Brent and Betty some love and support, but it was huge for all of us.”

The guitarist highlights another memorable moment during the recording of “Nobody’s,” a rocker in the early ‘80s mode. “They put these $20 thousand microphones all the way down Front Street because Betty wanted to record Brent’s new Harley Softail as it reached its top RPM, and I then I was to slide into my guitar solo. It was crazy, but remember that this is way before sampling. The first time he went down the block, he didn’t have high enough RPM. So he did it once more and he crashed the motorcycle at the end. I was freaking out, but he was fine and he said, ‘All of this so I could get Monty to play a guitar solo.’”

“I got to know Brent pretty well,” Marshall recollects. “I stayed at his house. We had meals together, hung out. It was a wonderful time. Brent was a sweet guy with good taste in food and wine, an amazing keyboard player and singer, and had a good, dry sense of humor, too. He was a pleasure to work with on the sessions—very patient, very focused. And I really liked the songs. So everything about the project was pretty great. There were always plenty of mind- or mood-altering substances, so that might cloud my memories of the sessions a bit, and they might have had some effect on my playing at the time. But John, Brent and Monty were so good that we always got goodsounding tracks, and if I had a note or two that needed fixing, that’s what I did.”

Copyright records confirm that Mydland composed both the music and lyrics for all of the songs, which include “Inlay It in Your Heart,” “Dreams,” “See the Other Side” and “Long Way to Go.” Much of the material gravitated to love songs with the light-FM sheen of the era, which was reinforced by the fact that Mydland’s vocals often were evocative of Kenny Loggins or Michael McDonald. Two songs would later make it into the Grateful Dead repertoire: “Tons Of Steel,” (eventually recorded for In The Dark, where it opens side two) and the aforementioned “Maybe You Know” (somewhat infamous in Dead lore for a version Mydland performed while impaired on 4/21/86).

The recording process stretched on into a year, which was a reflection of Mydland’s perfectionism. “I started going to the Dead shows, and other than Jerry, Brent was the hardest-working guy up there,” Byrom explains. “I sat on the B3 stool with him one night in Santa Clara, and honest to God, I watched him go through three B3 organs in one song—in one tune. How do you do that? Three! Not two! They rolled one out and he said, ‘This one ain’t good enough. Give me another one!’ And he was right. But he was a perfectionist, which is a curse in music. I’m a bit of a perfectionist myself, but at some point, you have to let it go. You have to accept things that maybe aren’t perfect, but they’ve got the feel. We wouldn’t have a Jimi Hendrix record if that wasn’t the case. So that was the only curse with Brent. Every harmony had to be perfect, and I’d think, ‘Brent, man, it could be a little flat. It’s still good. It’s you.’

“As a future record producer myself, I learned from that and later applied it. I lost my fear by watching his fear and I make records really quickly now. Eventually, with Brent, the overdubs were like pulling teeth and I’ve never made a record like that since. I’m not the only one that felt that way. Betty was the same way. She was like, ‘That’s good enough, Brent. That’s really great.’ But being an artist was new to him, even though he was the keyboard player for the Grateful Dead. I think he had a hard time calling himself an artist, although he truly was, in every sense of the word.”

After a year of working on the record with Mydland and regularly refining it, Byrom eventually moved on. Billy Satellite recorded its self-titled album for Capitol with producer Don Gehman (John Mellencamp, R.E.M.) and opened a tour for Jefferson Starship. The group disbanded after that one record, although “I Wanna Go Back,” co-written by Byrom, became a Top-15 song for Eddie Money a couple years later.

Mydland soon lost enthusiasm and momentum. “We split up and the project kind of fell apart,” Cantor-Jackson recalls. “I had mixed it all, but Brent couldn’t locate some of the mixes. He tried to mix some, but they didn’t sound quite the same.”

The original mixes, as well as the alternate versions, quite likely exist in the vault today— a proposition that continues to rankle Monty Byrom. “It’s not right that that record should die a cold death in a dark closet. I’m sorry, it’s just not right. It’s not fair. Even if it sounds like 1982, that’s his one solo record.”