Bob Marley: A Legend at 70

In honor of Bob Marley’s 71st birthday, we look back at this piece reflecting on his 70th…

“Woy-Yoy!” calls out Stephen Marley, clutching his head in his hand, momentarily holding a pose that’s reverently reminiscent of his late father, Bob Marley. To his left, his brother Ziggy bounces to the hypnotic pulse. Stephen turns the microphone and extends it to the masses tiered up into the darkness of the Hollywood Hills. “Woy-yoy!” respond 18,000 people at the top of their lungs.

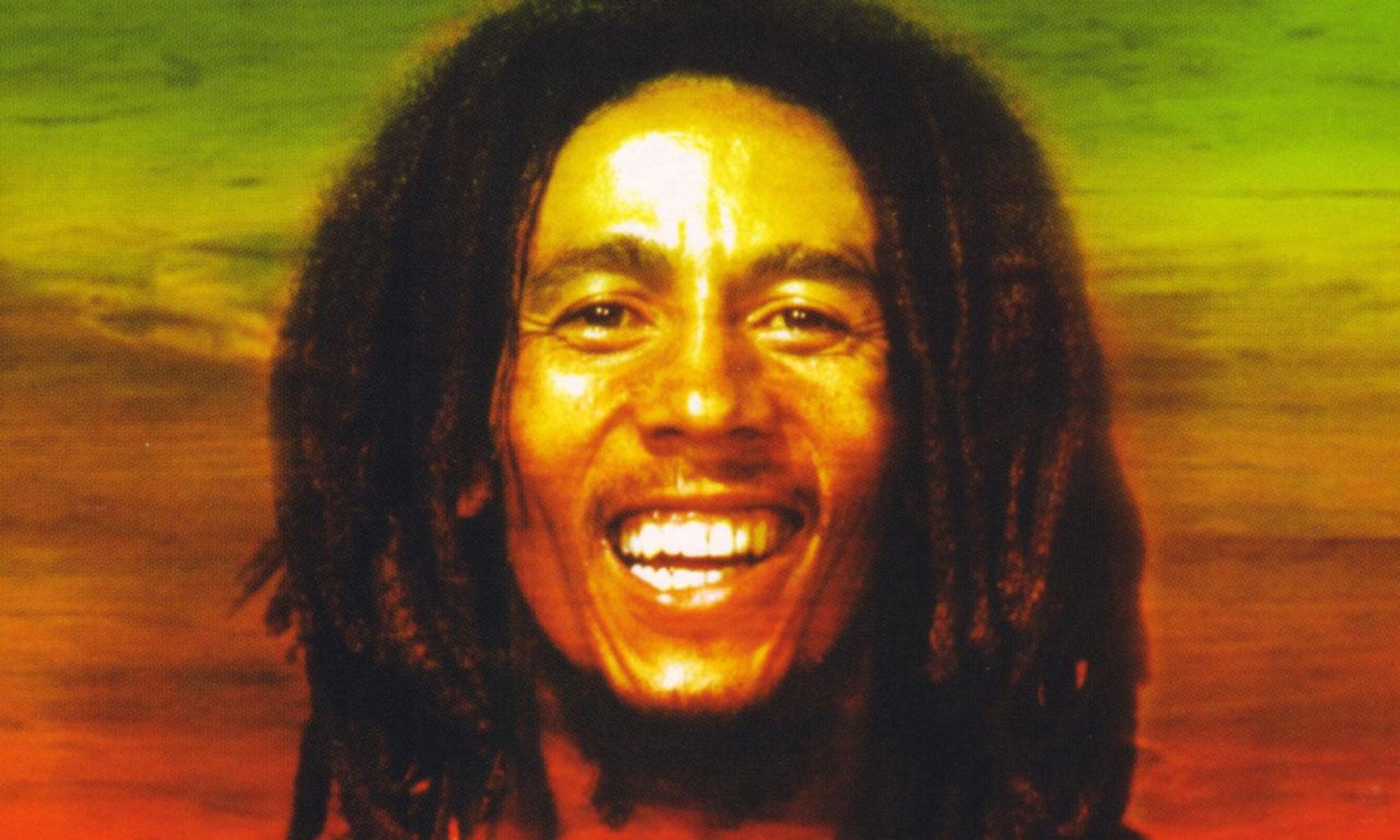

As his 70th birthday arrives, Marley’s allure remains magnetic and mystical. Despite his passing 34 years ago, the life and music of this reggae artist from a Third World island nation still feel very much alive, continuing to intrigue, entertain and entice. Given the sum total of his name, artistry and visage, Bob Marley is possibly the most identifiable person on the planet. His story has been told through documentaries, books and even the Marley musical. His words are quoted in the speeches of world leaders, and on T-shirts and bumper stickers. His voice, face and brand are instantly recognizable to generations of music fans, and his music is heard throughout the world.

Robert Nesta Marley was born on a farm in the countryside village of Nine Mile in St. Ann Parish, Jamaica in February of 1945—the son of a young Jamaican woman and an elderly, white Jamaican World War II land overseer and vagabond cast out from his wealthy family. From an early age, Marley was drawn to music, often playing with his friend Neville Livingston in rural St. Ann, before both moved together to the Kingston ghetto of Trench Town when Marley was 12. It was in Trench Town that Marley and Livingston, who would rename himself Bunny Wailer, met Winston McIntosh, better known as Peter Tosh, and formed a singing group. They made their debut as The Wailers in 1963 and, within a decade, the trio of Marley, Wailer and Tosh were crowned the reigning kings of reggae.

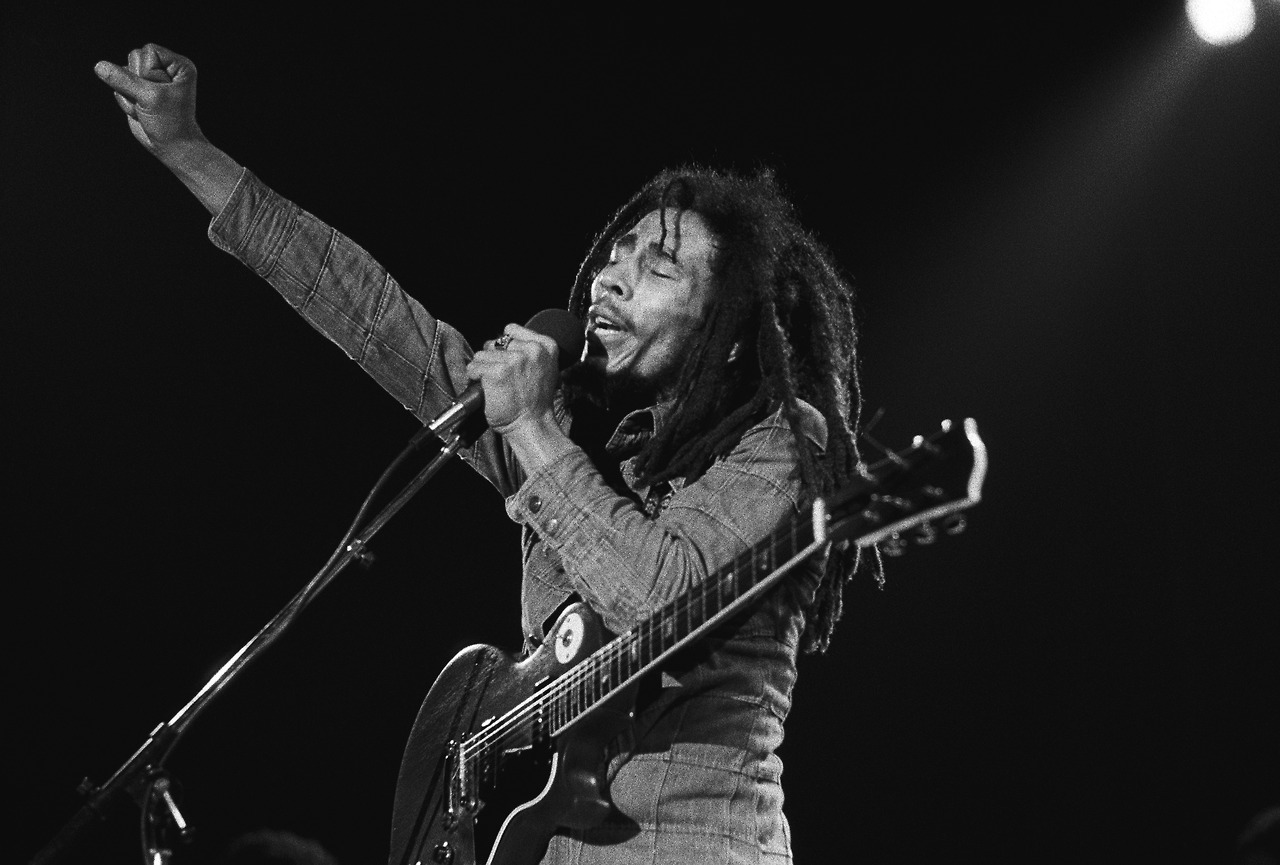

It is a mid-August Sunday night and the Hollywood Bowl is on fire. Los Angeles is in the grip of triple-digit heat as Ziggy and Stephen, Marley’s oldest sons, take the stage to perform together on this special evening commemorating “Bob Marley’s Roots Rock Reggae: A 70th Birthday Celebration.” Backed by a band combining musicians from their respective solo groups, the siblings offer some welcome, cool relief on “Simmer Down,” The Wailers’ first single and Jamaican chart-topper in 1964. Ziggy’s longtime drummer, Carlton “Santa” Davis, holds the anthem’s ska uptick flawlessly in check.

Santa is a living link to Marley’s cornerstone period at Studio One. A Jamaican native, the beat-keeper grew up listening to The Wailers as a teenager, then played on sessions with Marley in the early 1970s. “During those days, there was a fleet of artists who were great. I don’t think I thought of them as breakouts,” Santa recalls of his first impressions. “The Wailers were one of a group [of successful artists].”

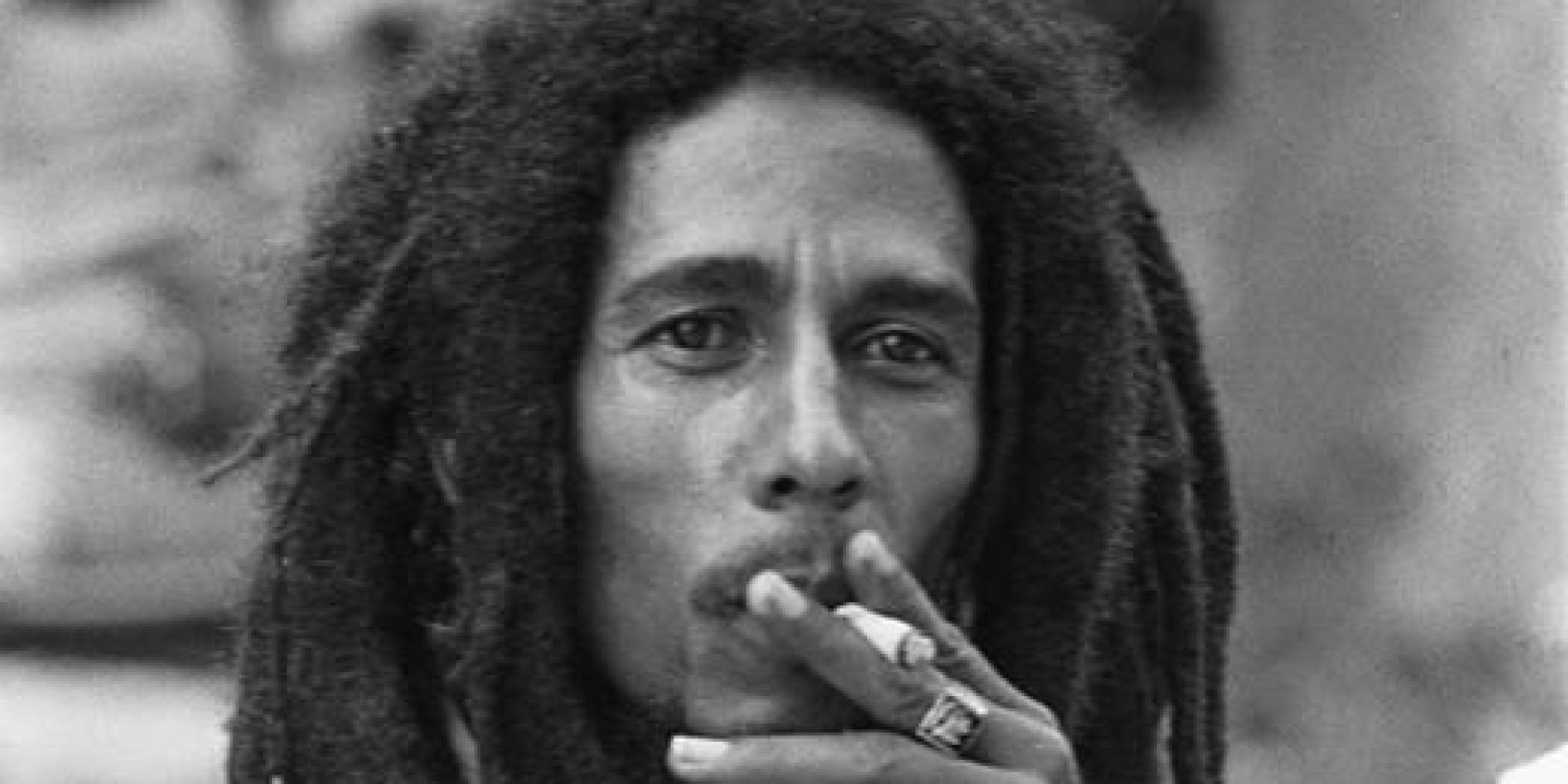

In 1972, Marley turned 27 and reached a crossroads. He was talented and strong- willed, owning the street nickname Tu Gong. He had also been married to his wife Rita for six years and was a father to Cedella, Ziggy and Stephen, as well as Rita’s daughter from a previous relationship, Sharon, who Marley had adopted. He’d spent some time in America, as a janitor, briefly shelving music before returning to Jamaica with renewed purpose. He had also embraced the religion of Rastafari, started to use marijuana and grown his hair into dreadlocks. This was the gestation of what would be the most significant trinity in the transformation of Marley’s eternal image.

Today, murals of Marley exist on the streets of San Francisco and in the African bush, on the walls of the Hotel Bob Marley in Muktinath, Nepal and in the alleys of Moscow and Rio de Janeiro. The majority of the artwork depicts a smiling Marley garnished in splashes of red, yellow and green—his long, natty mane regal like a lion’s—often holding his guitar or smoking a joint. But those iconic images only tell part of Marley’s true story.

“The peace and love thing is a strong part of what he was saying,” admits Ziggy. “But, he was also a very militant, revolutionary-minded person. The everyday fans don’t recognize that side of him as much as they recognize ‘One Love,’ ‘smoke herb’ and ‘everything is alright.’”

The Wailers started to transform both their music and their public persona in the early 1970s. Bolstered by the consummate rhythm section of the Barrett brothers, Carly and Family Man, the band signed with Chris Blackwell’s London-based Island Records and released their pivotal debut, Catch A Fire, in April 1973. They shed the matching suits, smiles and upbeat ska of the ‘60s, adopted a new revolutionary look and ethos—patchwork denim jeans, pensive expressions—and started playing topical songs about slavery and social injustice. The music, now in one-drop rhythm, was slower, darker and serious.

Even Catch a Fire’s cover art was a statement of incendiary duality. Designed in the guise of a Zippo lighter, the album opened from the top, as if hinged, to reveal vinyl possessed by an equally combustible assemblage of tracks like “Concrete Jungle” and “Slave Driver.” Santa recalls The Wailers, of that time, creating a new, provocative identity. “It dawned on people, ‘Oh, wait a minute,’” he says of the perception of the reconstructed group. “Now they had a unique vibe about them.”

Even Catch a Fire’s cover art was a statement of incendiary duality. Designed in the guise of a Zippo lighter, the album opened from the top, as if hinged, to reveal vinyl possessed by an equally combustible assemblage of tracks like “Concrete Jungle” and “Slave Driver.” Santa recalls The Wailers, of that time, creating a new, provocative identity. “It dawned on people, ‘Oh, wait a minute,’” he says of the perception of the reconstructed group. “Now they had a unique vibe about them.”

The prodigious quintet quickly followed up that groundbreaking album with Burnin’ in October of ‘73. It featured a Marley composition, “I Shot the Sheriff,” that Eric Clapton would cover in 1974, turning The Wailers into an international name. But it was also the last album Marley, Wailer and Tosh would record together. Soon after, Marley ostensibly set out on a solo career, rechristening his outfit as Bob Marley & The Wailers in time for 1975’s Live!. The live album included his most successful single, the beautifully consoling ballad “No Woman, No Cry,” a vivid, unflinching portrait of Third World poverty and resilience that pulled back the curtain veiling daily life in Trench Town. Elevated by an indelibly memorable guitar solo from American musician Al Anderson, the bare and poignant rendering from London’s Lyceum Theatre catapulted Marley from modest island success to global superstar. Many critics still consider it among the nest songs ever written.

Of the 16 songs that the Marley brothers choose to ignite for the over-capacity crowd packed into the Bowl, including the opening “Redemption Song” and “Could You Be Loved” finale, 11 appear on Legend, the Bob Marley compilation album (first issued posthumously in 1984). Legend is a ceaseless record-selling machine, second only to Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon in number of non-consecutive weeks on Billboard’s charts (1,175 weeks as of the Bowl show). According to Billboard, the greatest hits collection sells roughly between 3,000- 5,000 copies every week.

“It’s still a powerful album. It’s a great introduction,” says Roger Steffens, author, lecturer, photographer and archivist of the largest privately-held collection of all things reggae. “And, hopefully, it will make people dig deeper into his catalog.”

There have always been curious bits of Marley lore. There are stories of him buying a BMW because it matched the initials of his band or that he turned down Jerry Garcia’s offer to sign with the Grateful Dead’s record label because he didn’t like the band’s morbid name. There is also the rumor that Marley did not write “No Woman, No Cry,” a song that is actually credited to his friend, Vincent “Tata” Ford. The latter story was actually challenged in court: Marley was accused of implementing the Ford credit to divert publishing dividends away from his manager, Danny Sims, with whom he was in a contractual dispute. Marley prevailed, and, it was said, that he added the Ford attribution so that Tata’s Trench Town soup kitchen could survive on the tune’s royalties. (Ford was cryptic to his grave and never revealed his true role.) “It’s Bob’s song, come on,” contends Steffens.

At the very least, the case revealed Marley’s savvy acumen for business that he passed on to his descendants. As CEO of Tu Gong International, Bob Marley Music Inc. and 56 Hope Road Music Ltd, Marley’s eldest daughter, Cedella, has been in the captain’s seat for over 20 years. She has overseen licenses to—and development of—hundreds of products that “align with our values” and have added to Marley’s tally as the fifth-highest-earning deceased celebrity. According to Forbes, Marley took in $20 million in 2014 alone.

“We are all very conscious of the responsibility we have to our father’s name,” Cedella explains. They agreed to market Marley Natural cannabis, but not to bobbleheads. “We all work closely to uphold his message and keep inspiring people around the globe.” Marley’s rising stardom in the mid-‘70s amplified that worldwide influence, particularly in impoverished countries primed for socialist upheaval, and generated backlash from right-wing governments fearful of his music’s ability to unify the disenfranchised. By 1976, Jamaica’s political climate had shifted from a tinderbox to an inferno. “We were always under pressure to be on some political side of something,” remembers Anderson.

Approached by representatives of the leftist People’s National Party, Marley was urged to play the Smile Jamaica concert in December to mollify the bubbling unrest among the youth. Violence had overtaken the country. Free from offering PNP his endorsement, Marley agreed to perform.

On December 3, 1976, two days before the concert, several gunmen stormed Marley’s home, ring shots that hit his chest and arm, struck his manager Don Taylor in the groin and penetrated Rita’s skull. Rumors ew that PNP opponent Edward Seaga, with the support of the CIA, ordered the attempt. Undeterred, Marley appeared as scheduled, even showing the crowd of 80,000 his arm, with a slug still lodged, and chest, where a bullet grazed his heart, then left Jamaica to record his next album, Exodus, in self-exile. Time magazine called it the “album of the century.”

Marley was a master communicator. His lyrics drew inspiration from biblical proverbs and the speeches of Emperor Haile Selassie, and three little birds sitting by his doorstep. “He had a tremendous, eloquent sense of poetic expression, and a gift of melody that was unsurpassed,” says Steffens, calling him the Shakespeare of reggae.

His songs were his weapons of change and his medium of affection. During his ‘77 stay in London, he released a version of “Keep On Moving” with altered lyrics, dispatching parental comfort to his children back home. “Tell Ziggy I’m Fine and to keep Cedella in line,” he sang.

This past May, cast members from the Baltimore stage production of Marley took to the streets, singing Marley’s songs in an attempt to assuage a city tugging between violence and peaceful protest. On a summer night in Pittsburgh, a Pirates coach ambled to the mound to counsel his struggling relief pitcher while Marley’s voice rang out over PNC Park’s public address system: “Don’t worry about a thing, ‘cause every little thing, gonna be alright.” “He could get a few words out,” Ziggy says in understatement, when asked what his father would think of the social-media age.

Marley was exceptionally skilled at distilling his message to its highest proof—unfiltered and pure, or stinging among the sweet—the One Love rebel armed with words and music. Consider but one of his verses within the co-ed party anthem “Jamming,” like “No bullet can stop us now/ We neither beg nor we won’t bow/ Neither can be bought nor sold.”

Critics initially dismissed his Island albums as reductive reggae made for middle-class whites. They probably were made for such a demographic, but the argument misses the point. Marley sang not only to give a voice of solidarity to the Third World, but also to be heard by the First; not to remind the under- privileged of their plight, but to “headucate” the rest.

Survival, from 1979, may be his most overlooked magnum opus. An entire album devoted to the historic struggle in Africa as many of its nations fought for independence, it is as empathetic as it is indicting. “He was very Africa-centric,” says Ziggy, citing Survival as his favorite of his father’s efforts. “He believed in fighting for freedom.”

Marley’s descendants continue that fight. At the Hollywood Bowl, Stephen’s son Jeremiah waves an Ethiopian flag featuring the Lion of Judah as Ziggy welcomes Cedella’s son, Skip, to the stage. Ziggy reminds the crowd to “tweet it out to your friends.” He’s marveling at the moment, imploring the sold-out Bowl to understand just how special this evening is for him, and for them.

Marley’s descendants continue that fight. At the Hollywood Bowl, Stephen’s son Jeremiah waves an Ethiopian flag featuring the Lion of Judah as Ziggy welcomes Cedella’s son, Skip, to the stage. Ziggy reminds the crowd to “tweet it out to your friends.” He’s marveling at the moment, imploring the sold-out Bowl to understand just how special this evening is for him, and for them.

Ziggy insists that he doesn’t normally play his father’s music with his brother the way they are playing it tonight. Stephen calls the show magical—he can feel his father’s presence. The firecracker snap of Santa’s snare launches “Roots Rock Reggae,” and the next generation of Marley steps into the spotlight. “Play I some music,” Skip sings. “This-a reggae music.”

The Marley website lists Bob as the father of 11 children—seven biologically outside of his marriage to Rita. They are all adults now—many middle-aged and living in the United States with children of their own—and almost all have already lived longer than their patriarch. Contributors to and keepers of the legacy, they have inherited the crown, as heavy as it may be, and for over three decades, they have continued the journey without a single public misstep to mention.

About half have chosen music as their profession, with Ziggy, Stephen and Damian (Jr. Gong) even finding Grammy-winning success. His sons Ky-Mani and Julian have also made their names, with grandchildren Skip, Daniel Bambaata and Jo Mersa recently entering the fray. Rita, whose aid to Marley’s career and memory carries on underappreciated, lives quietly out of the public eye; her foundation in Ghana supports local schools and women’s health.

There are college courses devoted to Bob Marley’s lyrics and their implications. In April, President Barack Obama visited his Jamaican home, saying that he still has all of Marley’s albums. Every angle, facet and theory of this mortal man—who died of a rare melanoma cancer in May of 1981 at age 36—continues to be detailed and debated.

Why is Bob Marley still so popular, and still so important?

“His message is universal,” says Cedella. “His lyrics, words and overall vibe made a lasting impression because we all want peace, justice and appreciation.”

“It’s all about the music, and everything we put into it,” says Anderson, who leads TOW: The Original Wailers, one of three currently touring bands composed of former members. (Family Man and Junior Marvin helm The Wailers Band and Junior Marvin’s Wailers, respectively.) Bunny Wailer performs periodically as well.

“My father’s music is like an owner’s manual to life,” Stephen reflects. “And it is so relevant today that it will always be popular.” Steffens likens Marley to a Horatio Alger rags-to-riches protagonist, and he calls him a Jesus gure who once supported 6,000 people a month. “He was all things to all people.”

“He lived through or he saw around him these situations he sings about,” offers Santa. “His songs were life stories for everyone. Everybody can connect to what he was singing because it was true.”

“We’re still here to keep his legacy going. That’s a big part of it,” Ziggy adds. “A second part of it is who he was. His personality, his spirt, his aura, his message, his music—people will always be connected to that. I think people imagine Bob being a friend of theirs.”

As the 70th birthday celebration at the Bowl nears its conclusion, over a half-dozen of Bob Marley’s youngest grandchildren join Ziggy and Stephen onstage. They sing and dance and jump around. “Woy-yoy!” call out the Marleys. “Woy-yoy!” responds the world.