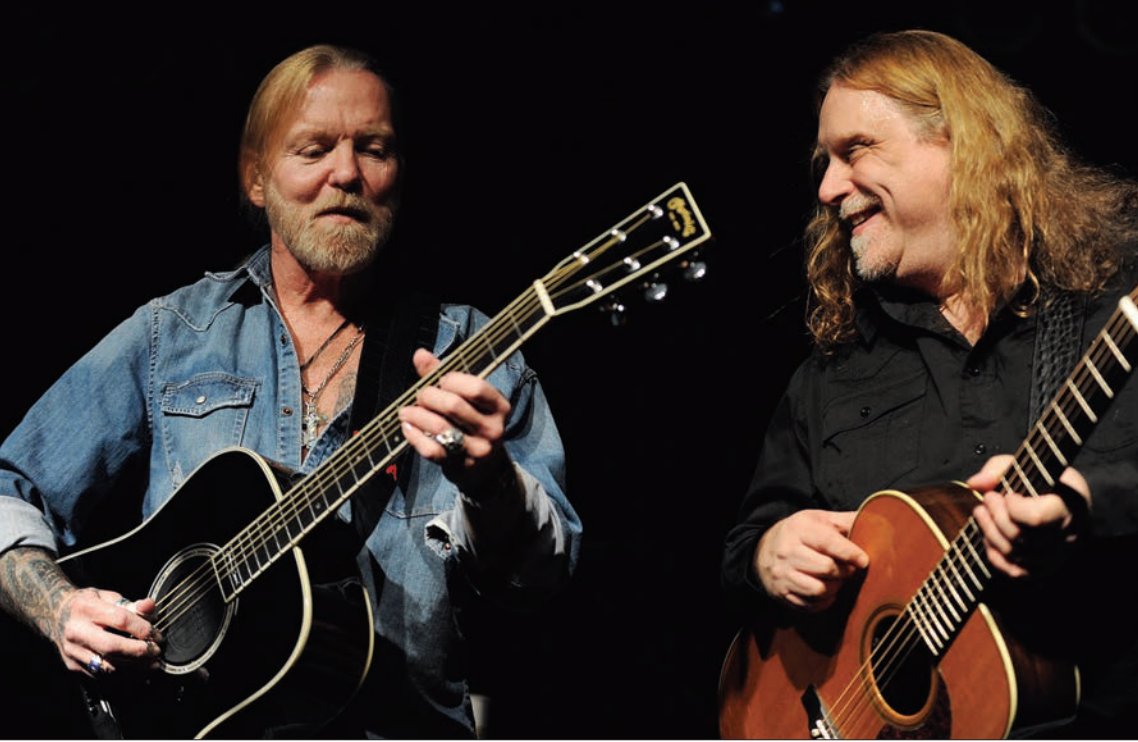

All My Friends Part I: Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks and Oteil Burbridge Remember Gregg Allman

Gregg Allman’s bandmates and confidantes reflect on his life and music.

Gregg Allman’s bandmates and confidantes reflect on his life and music.

Warren Haynes

You and Gregg wrote many songs together during the past few decades. What was your creative process like?

Some of my fondest memories are of us writing songs together. He was a rare, old-school individual, who was never in a hurry to finish a song. If it didn’t look like it was going to be finished today, then maybe we could look at it tomorrow— and if it didn’t look like it was meant to be finished tomorrow, then maybe we’d look at it next week. But he always came up with certain little changes that I would never think of on my own, which is quite ironic, considering how long I’ve known him and how much I loved and studied his music before I even met him. He always had a way of making things seem complete when they finally were. Until that point, he always felt a song wasn’t finished. Our process varied from song to song: Sometimes he would write more of the music and I’d write more of the lyrics, and sometimes it was vice versa.

What struck you the first time you saw Gregg perform live?

I never saw the original Allman Brothers because Duane died when I was 9 years old. The first time I saw Gregg was in a club when I was in my 20s, and he had not yet signed to Epic, which was his comeback with I’m No Angel. I remember seeing him several times around then and he always sang his ass off. The band at that time was really good as well—Dan Toler, a fantastic player, was on guitar and his brother Frankie was a wonderful drummer. I heard them do “I’m No Angel” quite a long time before he ever recorded it and I remember commenting then: “That’s a great song.”

We first met in 1981 and played together a couple of times, but then I didn’t see him a lot until he recorded Just Before the Bullets Fly, which contained my song as the title track. And, about a year later, they invited me to join the Allman Brothers, which is really when he and I started becoming close friends.

Gregg often downplayed his musicality, but he was a great organ player. Describe his approach.

Gregg’s voice will go down as one of the great voices in rock history. His organ playing was very understated, but it was always perfectly placed. What he played fit the music as well as anything possibly could. He had an uncanny sense of being able to fit in with the two guitars and stay out of the way, while still contributing in an extremely valid way. The sounds he got out of a B-3 were always impeccable, which is really the most important element of organ playing— being able to capture a great sound. And he was also a great fingerpicker on the acoustic guitar. I loved to sit around and watch him tune the guitar to open G and get into his folk side, which was always one of my favorite things about his musicality—the melodic, sweet side of him that was so beautiful.

Derek Trucks

While Gregg will always be remembered for his voice, can you talk about him as a Hammond player?

I think that’s probably the most unsung part of his musicianship. I’ve never heard anyone else that sounds like that on the Hammond—the way he would work the drawbars and certain chord swells. It didn’t matter what headspace he was in, it would just be so second nature to him—even with tunes like “Jessica,” he would always just nail it. He was one of the most tasteful B-3 players ever. There’s no one else who sounds like him in the realm of whatever we call what the Allman Brothers did. He had a very singular sound.

The rhythm section in the Allman Brothers was always this propulsive, mysterious thing that was part of the magic, but the sound of Gregg’s B-3 was a huge element to that. The intro to “Dreams,” that stuff gives you the chills before anything else shows up—before the lyrics and the Duane solo, when it’s just the drums and the sound of Gregg’s B-3. That’s what probably drew me in without even knowing it. It’s sneaky good.

What’s the first song that comes to mind when you close your eyes and think of Gregg?

When I first got a CD player as a kid, and would put on headphones, I remember burning out “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More”—just the sound of his voice, the way he sang that line, “We’ll raise our children,” the way he pegged that microphone. When I heard that he passed, that’s the first song I went to and that’s when all the emotions came crashing down—just listening to him sing that tune and thinking about what he was going through when he sang that song and what it was like being on stage playing that particular song with him.

“Dreams” and “Please Call Home” also come to mind when I think about him—there’s so many great moments, but there’s something about “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More.” He really was a unique combination of things that don’t often come along. There’s a lot of great musicians that came along in the jamband scene, but no one had a voice like him—had that much fucking mojo, that vibe and that voice. I can’t tell you how many people I’ve run into from all walks of life, whether it was George Jones or Herbie Hancock, who say, “Oh, you play with the Allman Brothers—Gregg’s voice.” He pretty much crossed all boundaries, and he gave credence to our whole scene, even when people didn’t know what was happening.

In the ABB, Gregg balanced so many musical elements. There was that time he called out you, Oteil and Jimmy for taking it too far out on “Mountain Jam,” and then he came back and apologized.

That sums up his feeling about being in the Allman Brothers Band from the beginning. He wanted it to be the Bobby Bland band, and Duane wanted it to be the Bobby Bland band and the Miles Davis band. [Laughs.] There was always that dynamic, and when that went down, we were just early into the era with me and Jimmy, which only lasted a year. And, in some ways, it was the first time that it wasn’t Duane or Dickey running the band. Gregg was trying to sort out what he wanted it to be or see how far he wanted to let it go.

It was just him, in real time, either trying to put his stamp on it or realizing, “Wait a minute. There’s already a momentum carrying this thing; it just is what it is.” That’s what it felt like to me— I didn’t take any offense to it. I thought it was hilarious even when it happened. He was like, “Who’s the Phish fan?” and I remember being a smart ass and I was like, “Not me.” [Laughs.]

Then, he went to the back of the bus after telling us, “That was just too far” and he started thinking about his discussions with Duane. So he came back up, and said something to the effect of, “Me and my brother used to go round and round about that shit.”

Oteil Burbridge

Do you recall the first time you heard Gregg and the music of the Allman Brothers Band?

The funny thing is, I didn’t really know the Allman Brothers stuff at all. I was at this party in high school, and I heard what I thought was Tony Williams Lifetime because the organ was screaming like Larry Young. Plus, there was the sound of Duane’s guitar, and there was the double drums, which sounded like Tony Williams. I stopped dead in my tracks, and I was like, “Who is that?” And my buddy Claude said, “Dude, you don’t know who that is? That’s the Allman Brothers Band.” What I was really keying in on was the drums, and the organ and the guitar. It was in the jam part of “Whipping Post.” And I was like, “Allman Brothers Band. Wow, those are some badasses.”

Can you talk about being inside the belly of the beast when you started finding your way within that music back in ‘97?

It was so crazy because I had never been in a really big band, and I had never been in a band that was really dysfunctional like that. The whole dynamic between Dickey and Gregg and Butch—I didn’t know what to think. It was just overwhelming. The drummers had their own bus, Dickey had his own bus and then me, Jack Pearson and Gregg were all on one bus. It was a very welcoming environment, and they left me out of their dysfunctional dynamic, but it was definitely a tumultuous time when I joined. I honestly didn’t expect it to last longer than the summer because Warren and Allen Woody had just quit. I thought, “They’re bringing us in to try to save it, but it’s probably going down.” Seventeen years later, they were still going.

The music was intense. I’ll never forget the very first two songs I learned were “Don’t Want You No More” and “Cross to Bear.” That’s also how it started out that very first night, and I remember that, for whatever was going on offstage, when we’d get onstage, there’s was some very intense mystical stuff going on. It made my hair stand up.

How would you characterize Gregg’s musical legacy?

Any artist hopes to make something that will stand the test of time—that will outlive them. He really tapped into it. Those first five records? It’s timeless music. There are lots of people who are trapped by their hits, but his songs never get old. He left the world a more beautiful place than he found it. There are people that haven’t even been born yet that are going to get inspiration from what he did. And for Butch and Jaimoe and Dickey and Duane and Berry and Lamar and Chuck, and everybody that’s ever contributed to this, it was the inspiration for so much yet to come. You’re going to hear Gregg and his music and his whole essence in other people’s music. I’m sure pieces of it are going to be in the music that I write in the future. I’m also really glad that he made it as far as he did, when so many of his brothers didn’t.