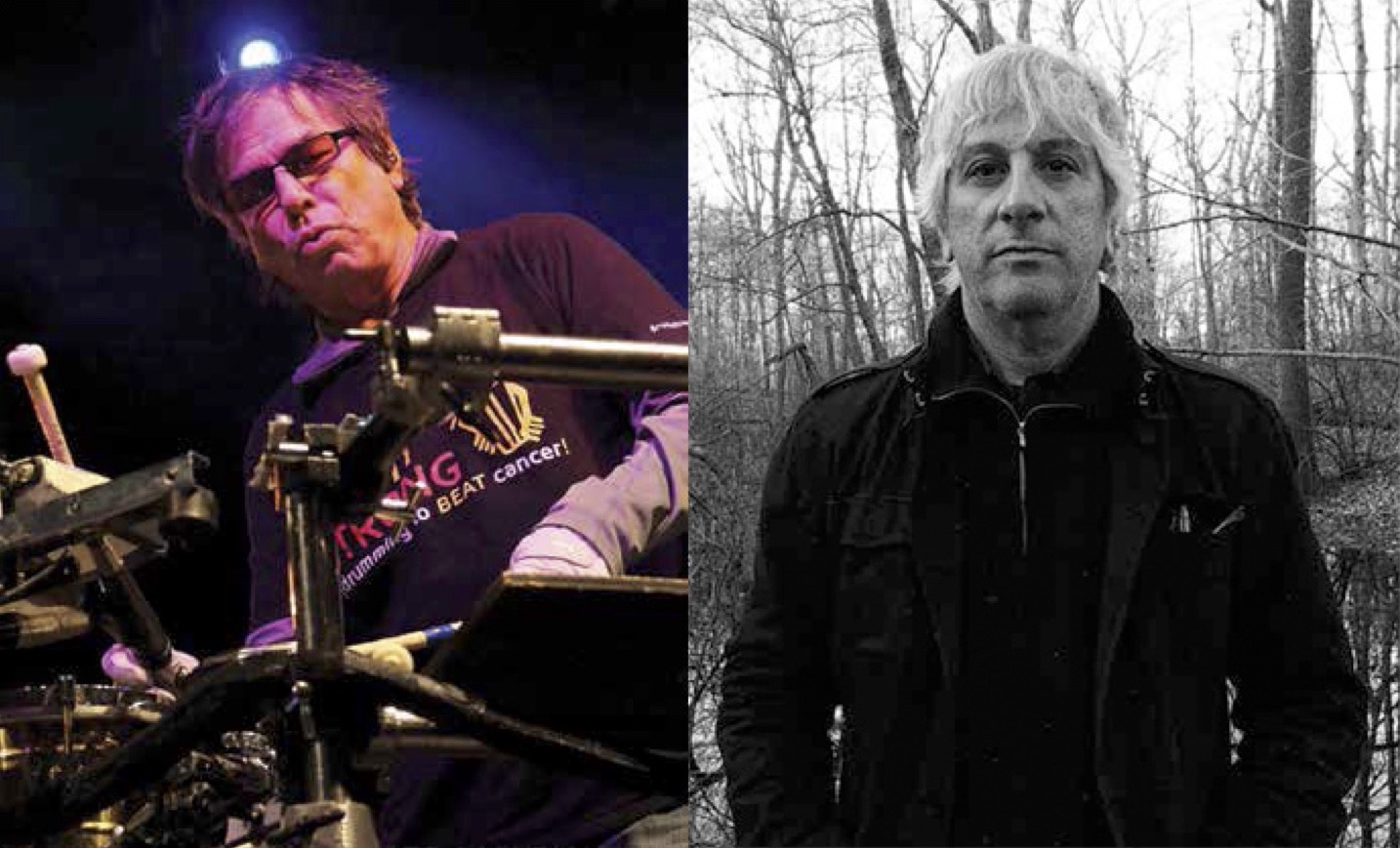

A Conversation with Mickey Hart and Lee Ranaldo

This story originally appeared in the July_August issue of Relix featuring a variety of pieces on the Grateful Dead’s 50th anniversary. To subscribe, click here.

“How did I get into this? I got an answer for that one—I didn’t have a choice,” says Mickey Hart. “The muse led me to this. I didn’t really think there was any option in my life besides playing drums. That’s all I wanted to do, and I still want to do it every day.”

Hart, one half of the Grateful Dead’s drumming duo, has also had a successful career outside of the band, even winning two Grammys for his forays into world music, but it all started in 1967 when he met Bill Kreutzmann in the crowd at a Count Basie concert. Guitarist Lee Ranaldo—who co-founded Sonic Youth in 1981—shares many of the improvisational and experimental musical sensibilities espoused by Hart and the Dead, though he created his works in a wholly different time and space.

Speaking from opposite sides of the country, Ranaldo asks Hart about the Dead’s early history, techniques and evolving legacy.- Matt Inman

LR: I got into improvisation because when we started in New York, at the time, people were doing all kinds of experimental things in music—listening to song forms, but also leaving song forms behind and playing more out-there music. Sometimes it was called noise. I see a parallel with the Dead in that you are such masters at moving from a song right into an open- ended free space and then back.

LR: I’m curious—what you’re talking about is when you started playing the Acid Tests and all of those early shows where it was much more freeform. As it moved into shows that included a lot more songs, was it difficult to keep those spontaneous bits happening?

MH: That’s a good point. In other words, it’s like a rehearsed jam. We knew what we were gonna do in certain parts because we jammed around them so many times. So being lazy or whatever, in a rut, you go into your soundalike jam. It happens a lot. It happened to us as we jammed. But it was really hard—how many things can you say? There’s only so many ways you can play something. So we exhausted a lot of avenues—some good, some not so good, some completely off-the-charts horrible, but we were all looking for something. So we were not trying to recreate, it was more of a creational thing that we all really had in our gut. It was a constant reinterpretation of our own music every night. We had enough patience not to rush the songs. That’s why we played really long—you can’t really do that in normal song form. Then you take the good stuff, and that’s part of your repertoire. That’s how we did it, anyway. We played every day. We had the best time, in the early days.

LR: I love that you talk about patience because I can hear that when I listen to you guys. Nobody’s rushing to get to the end. Everybody’s just there for the moment and the exploration of what you’re doing.

MH: You gotta give, you gotta take. That’s the suspense, the anticipation, that you use. You’re spinning this web, and you’re taking people on a trip—including yourself. Not only did we play together every day, but we also lived together. So that was an attraction, no extra charge. We were so close—it was a tribe. We all were together all day, every day. We became a family, as opposed to just bandmates. Being bandmates was secondary, actually. The way I see it, we were tied at the heart in a very specific way that came out through the music.

LR: The thing that struck me most about the Dead is the depth of the songs and the songwriting. It’s kind of mind-blowing how many great songs this band had, with lyrics espousing a more personal kind of politics that saw a much longer view than politicians ever get to take.

MH: We were sending another message out. But we were angry, and we were playing hard. You had cutthroats and thieves in the White House, and you had a war going on for no good reason, and the National Guard was coming out and killing college students. So it was getting out of hand, right there at the brink. The music, I thought, mediated some of that. Our weapon was Robert Hunter—great lyricist, prince of words. He spun the whole mythology. These songs were like a miracle. They would make sense at a time when you couldn’t make sense of the whole thing. He was our voice. He wrote the lyrics. Without that, you wouldn’t get the message. So how important is he? Well, as important as we are. He’s the fifth Beatle, all right.

LR: The first time I saw the Dead was about six months after Pigpen died, so I never saw the band with him. He’s a big factor in the early period of the band that a lot of latecomers don’t realize. He was maybe the first singing voice in the band that had this primacy.

MH: He was the best musician in the band. When we needed to get the audience off of their backsides, we’d just throw a Pigpen song in there. We would go, “Sooooie,” and Pigpen would appear, and all of a sudden the audience was up on their feet and dancing. He played a harp, he sang, he improvised and made up stories. He was an old blues guy. He looked like a Hell’s Angel. So we had a harmonica-singing Hell’s Angel as a frontman for the Grateful Dead. [Laughs.] Then the new stuff that was coming up, he didn’t really catch on to it. He was so deep into the blues, it kind of left him behind a bit. Then he started drinking really hard. He always was a drinker. He and Janis Joplin used to drink together. They used to cackle together all night long.

LR: You guys had many people come and go from the lineup over the years, and you were pretty welcoming to all of them. You talked earlier about this egoless quality of the band, and I could also sense that. You always had each other’s backs in a really wonderful way.

MH: That’s a good way of putting it, you bet. It’s like going out on a rough sea in a rowboat, and you know that if you don’t pull together, you’re doomed. But if you pull together, you’ll win—you’ll come out alive. It’s the same thing in this kind of music. Sometimes when we go so far out, we’re losing the “one” and everything is just floating beautifully. You look around and we’re all on the open ocean, and if we don’t row together, pow. But if we do— whoa. There’s power.

LR: You guys were one of the first rock bands to use two percussionists onstage. How did you come up with that concept?

MH: Well, it wasn’t planned—just like anything else. I was at a Count Basie concert, watching my main man Sonny Payne. There was a drummer in the audience there, who I found out was the Grateful Dead drummer. And this anonymous person, who I still don’t know—nor does Bill Kreutzmann—came up to me and said, “Hey, that’s the drummer of the Grateful Dead, wanna meet him?” I said, “Sure, why not?” I’d never heard the Grateful Dead, but I knew they were a new band in town. So we started talking and got on, and after the concert, I had two pairs of sticks on me. We went out and we just drummed our way around the city, on cans and street posts and cars. We just had a hoot. The next thing I know, he says “Hey, wanna see my band? We’re playing down at the Straight Theater.”

The first set, it was just cacophonous— it was just an open theater. And then Bill comes up to me and he says, “You wanna sit in?” I said, “Sure, but I don’t have any drums.” So Kreutzmann jumps in his Mustang and goes and gets a set of drums, sets it up, and that was the second set. Then we just went off, and that was it. When that ended, everybody seemed to think that was the Grateful Dead. Everything else after that, Lee, is hazy.

LR: How did you guys play together, as you were developing songs?

MH: A couple of levels. First of all, we didn’t play similar styles, and there was never any competition. That wasn’t the idea. The idea was to be a monster rhythm section and be able to go to places no one’s ever been before—not only as a pair of drummers in a band, but also with the band itself. It allowed rhythmic dexterity for all those other players, with this solid rhythmic carpet. That’s another part of the improvisation, when you have such a great foundation, such a solid pair in me and my associate, Dr. Kreutzmann. I’m saying it like it is. As far as I’m concerned, those guitar players were very lucky, very fortunate indeed.

LR: I think you were all lucky to have each other.

MH: I tell you, it was fun. We laughed our fucking asses off most of the time. So it wasn’t dark. There was no heroin and cocaine. It was just a good smoke and a few psychedelics, and that’s it. But the hard stuff wasn’t there. As soon as that started coming around, you know the story. There’s no mystery.

LR: Yup, changed everything.

MH: It sure changed the neighborhood. And it changed the music in a profound way because it broke down trust, and it broke down feelings, emotions, that are needed to play heroic music. You lost your compassion. Once you lose your compassion in music, it’s over. You might as well just hang it up and try another career because you have to have that. Everything breaks down. Once it starts to crumble, you can’t really relate at the highest level, have an intelligent conversation as opposed to just a dumb conversation that’s stale and redundant in the worst ways. And the will, that’s the other thing you need. Those things take your will—the will to play, the will to succeed, the will to live, everything.

LR: I know you’re inside of the whole thing and it’s hard to maybe answer this question, but do you ever think about the Dead’s legacy? Do you ever kind of scratch your head and wonder how this happened to you particular bunch of guys?

MH: Magic, you know? Really hard to predict that. All of the young people that are picking it up and playing it, that’s what propels the legacy deep into the fabric of the world. We had no knowledge that [the 50th anniversary shows were] going to be an avalanche of people. We mis-judged this completely. We didn’t know who was out there and who would even care. But we were really wrong about that, and that’s a horrible thing to say—not thinking that there would be people out there. They’ve supported us our whole lives. Can you imagine how long they have been with us, and how many shows they’ve gone to? Some of them have gone to a thousand or more.

LR: Not as many as you’ve gone to.

MH: They keep coming back for more! I don’t know, man.

LR: With good reason. We love you guys.