The Day the Music Died in Kingston

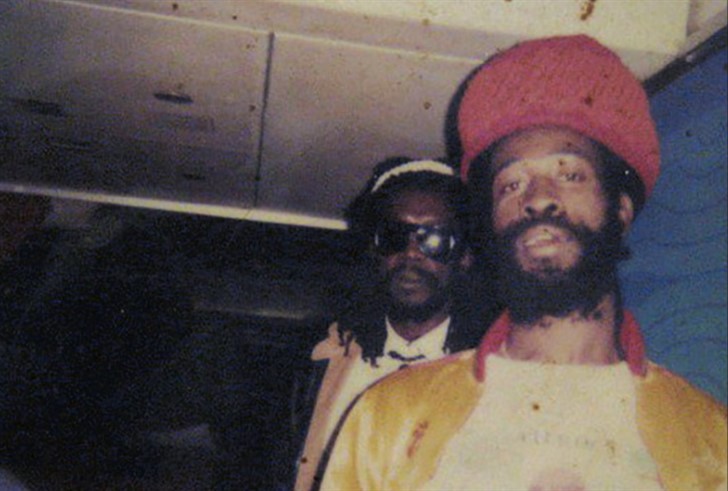

Courtesy of Santa Davis

Courtesy of Santa Davis

Pioneering reggae drummer Carlton “Santa” Davis has worked with notable acts like Bob Marley & The Wailers, Jimmy Cliff, Black Uhuru, Burning Spear, Big Youth, The Aggrovators, Soul Syndicate and Roots Radics, among others. He currently plays with Ziggy Marley.

The story that follows, chronicling one of the darkest moments in music history, is in Davis’ own words as told to writer Larson Sutton.

On Sept. 11, 1987, I was at Peter Tosh’s house, lying on my stomach, with a gun pointed at my head. I thought I was going to die. At various times, and by various people, I’ve been asked about what happened that night. I have chosen to speak publicly about it only a few times. I understand people’s interest and their fascination. But, for me, it’s something I rarely want to remember and I know I will never forget.

Peter Tosh was my bandmate, my friend, a brother to me. There are people that have suggested things about the events of that night in September that are just not true. It is hurtful and sad to hear these false accounts. Six people, including me, were shot. Three, including Peter, were killed. I will tell what I remember about his death, but first, I want to talk about Peter’s life and my time with him.

I grew up in Kingston 13 in Jamaica, in Greenwich Town, but everyone called it Greenwich Farm. From the start, I was surrounded by music. Jamaica has always been a place for music— work, food, music.

People would get done with their shift, stop to pick up the latest single, and play it on their turntable immediately when they got home. Every bar had a jukebox playing. Every corner store or restaurant had music playing. In their spare time, folks would sit on their steps or street corners every day listening to calypso, ska, R&B, reggae—everything.

There was radio, but it was the sound system that ruled in Jamaica. On weekends, dance halls would open and men would bring in their speaker boxes and turntables. In the trees or on the roof, they would wire up steel-horn speakers. You could hear the music for miles. Sometime they would even put their systems on the beds of pickup trucks, driving around Kingston like mobile disc jockeys.

In the 1960s, my neighborhood in Greenwich Farm was right in the middle of it all: Three competing dance halls and three competing sound systems, playing music every weekend until 4 a.m. It was festive; the streets were lined with people drinking beer, smoking weed, and vendors selling coconut water and sugar cane. When I was about nine years old, this is where I first heard The Wailers.

“Put It On” is probably the first Wailers song I remember hearing—that and the early ska version of “One Love.” I liked them, but I don’t remember thinking of the group much more significantly than other artists of the time, like Alton Ellis.

I played drums in a church youth group. I enjoyed it and was encouraged by the senior members to continue playing. They saw something special in me. By the early 1970s, I was the drummer for the Soul Syndicate, a top local rhythm section that performed live and did a lot of session work backing vocalists.

Lee “Scratch” Perry was a funky, freaky, groovy mad professor—one of the greatest producers ever. He called the Soul Syndicate in for a session at Dynamic Sounds. It was with The Wailers.

By now, The Wailers were well-known hit-makers. They had not yet left to sign with Island Records and become international superstars, but they were at the height of their early days in Jamaica. Believe me when I tell you: When these brothers walked in the studio, they had presence.

The Kingston music community at that time was relatively small. This is Jamaica in 1971. A lot of people didn’t even have a phone. Musicians would gather near studios like Randy’s, in bars or on a small lane called Idler’s Rest. If a producer needed a player, he’d come asking. There were plenty of musicians, but really only a handful played on most of the records. You either had it or you didn’t, and producers like Lee “Scratch” Perry definitely knew those who had it and those who didn’t.

That first session with The Wailers, there was little in the way of talk. Peter, Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer sat together alone in a corner working out the vocals and guitar parts. We recorded “High Tide or Low Tide” and, at another session at Randy’s Studio, cut “Sun Is Shining” and “Mr. Brown.” As meetings go, it was exciting; but otherwise it was somewhat routine. New to them, The Wailers called me “Drummy.”

In 1976, I was hired to tour with Jimmy Cliff. On the success of the movie and soundtrack, The Harder They Come, Cliff was an international smash. That same year, Peter released his first solo album, Legalize It.

Bunny Wailer told Peter about me, saying: “When you put your band together, this is the drummer you need.” And Robbie Shakespeare, the great bassist, encouraged him to bring me in for the Legalize It session. We recorded “Ketchy Shuby,” and it was terrific, but I’d already made a commitment to Jimmy Cliff. Peter understood. On the album, I was credited simply by my nickname, “Santa.”

So say, so done. Five years later, a BMW pulls up next to me on a street in Halfway Tree. It’s Peter. “Are you ready to saddle up, now?” He was asking me to go on tour. This time, I was available.

For the next six years, the last six of his life, there were very few days when I didn’t see him or speak to him—I toured the world with Peter Tosh at the peak of his international fame. I remember the frenzy every time we performed.

Once, in Swaziland, he left the stage and went into the crowd. They lifted him up and passed him around over their heads. He was like a kid, enjoying every minute.

Yes, he had the guitar in the shape of an M-16 rifle. Yes, he sang of rising up against oppressors. Yes, he was angry. Who wouldn’t be after having been beaten within an inch of his life for having a little spliff?

But, the Peter Tosh I knew was accommodating, generous and kind. He was quiet, speaking only when he had something to say, and he had a great sense of humor. He was humble and always gave what he could. A voracious reader, Peter prided himself on being aware of the world he lived in.

He was also the consummate professional. He was never late and always performed at his highest level. As musicians, he treated us like pros and trusted us to the fullest extent, even letting us write each night’s setlist, usually nodding a simple “Yeah, mon” in approval. He made us feel like he was working for us; not us working for him.

Dennis Lobban was known around Kingston as “Leppo.” He had done time in prison and was one of the many that came around Peter when he became successful. Peter was a caring person who would o er help, but some, like Leppo, made a habit out of asking.

Peter’s common-law wife was a woman named Marlene Brown. She was evil in negative, controlling ways, hammering a wedge between Peter and many of his closest friends. Peter even raised his samurai sword at Bunny at Marlene’s bidding, driving Bunny away.

What I believe started the downfall of Peter Tosh’s life was a comment Marlene made to Leppo. She called him a “batty man,” a derogatory Jamaican slang term for homosexual. Leppo then accused Peter of having no control over his wife, and he began telling people around Kingston he was going to get Tosh.

That September night was a typically hot Friday evening in Kingston. Peter had returned from a trip to the States and I went over to visit. It was early, just after sunset, and others were at the house. Wilton “Doc” Brown and Michael Robinson were there—and Peter and Marlene. Jeff “Free I” Dixon, a local disc jockey, and his wife arrived later.

A few of us were sitting in the living room when Peter heard something outside. “Mikey, go see at the gate,” Peter said. Michael opened the door as three men came in, guns in hand. “This is a holdup. And, it’s you why this is happening,” one said in the direction of Marlene.

The room was dimly lit, and I sat in a chair between two curtains. A slightly open screen door was behind me. I wasn’t even sure they saw me. I recognized Leppo as one of the three, but did not recognize the others. “Dread, lay down,” one said to me.

They told everyone to lie on their stomachs on the floor. Our heads were in a semicircle, one next to the other. Leppo was asking Peter where the safe was, but Peter kept insisting there was no money in the house. “Monday, I go to the bank,” he said.

I was next to Peter. I heard the gun strike his flesh as they pistol-whipped him. I heard him grunt as they hit him over and over. It was heartbreaking, knowing I could do nothing to help my brother as they beat him while demanding money that wasn’t there.

Leppo took the $300 I had in my wallet and my watch. They didn’t wear masks, and Leppo, knowing he’d be recognized, said, “No partiality.” Like, even though we’d seen each on the street in the days prior, that didn’t matter now. When they were done taking our money, I heard one of them say to Peter: “You’re dying tonight.” For a moment, there was silence. And then the guns started ring.

I can only give thanks to the power of the most high. I believe I was the last one who was shot and, as they came to me, I felt the heat of the barrel against my head. I moved just a bit as the gun went off.

It felt like a pinch. I lied at on the floor, as though dead, and waited. After a few seconds, it was finally quiet. I heard noise outside, like a car pulling away and I stood up. I went first to the bathroom, worried the gunmen still may be in the house.

I waited a minute, but I felt odd. I told Marlene I was having trouble breathing and was losing all feeling in the left side of my body. I made my way to my Jeep. From there, I drove, with only my right side functioning, 10 minutes to the entrance of the University of the West Indies hospital. With whatever strength I had left, I leaned on the horn, and then collapsed into the arms of the alerted porters.

They wheeled me in on a gurney to the emergency room. Minutes later, Free I and Peter were wheeled in. On one side of me was Free I fighting for his life. He’s grunting and moaning, struggling to survive. On the other side of me was Peter. I don’t believe he was conscious. The doctors were over him, working furiously. Then, I heard a doctor say, “I’m afraid Mr. Tosh has left us.”

It was right then that it hit me: This was really happening. My brother was gone. Peter Tosh was dead.

Free I would die from his wounds. Doc Brown died as well. The nine-millimeter bullet that entered my clavicle caused internal bleeding and collapsed my lung. The doctors cut into my side to save my life.

After surgery, the police came and spoke to me while I spent a week in recovery. Leppo was arrested soon after and is currently serving life in prison. To this day, I believe, he says he is innocent of killing Peter Tosh.

That bullet is still in me somewhere. Years after the shooting, I had an X-ray done showing me its exact position, near my spine. A few centimeters the wrong way and I would’ve been paralyzed. I’ve been advised to leave it where it is.

There is a mark on my shoulder—more like a small discoloration—where the bullet entered. And there is a scar on my midsection where the doctors inserted the tube that drained my lung. These are the only reminders I need of what happened. Of course, I’m forever grateful to be alive but, otherwise, I’d rather not think about it.

Steven Rood

Steven Rood

Today, I am the drummer for Ziggy Marley. I’ve been with Ziggy for almost two decades. I like that I’m playing music that families can enjoy. As a husband and father, that is important to me.

But, the best time in my career was with Peter. It’s so sad that he was taken from us when really he was just getting started. I don’t want the memory of how he died to eclipse how he lived.

I remember him talking about apartheid when most of us didn’t even know the word. He wanted to do things with his success. He wanted to build schools, to help humanity. He was a visionary.

Just the other day on ESPN, of all places, I heard a sportscaster quote Peter’s lyric about equal rights and justice. I know the world misses the music and message of Peter Tosh. I miss my bandmate, my friend and my brother.

This article originally appears in the April/May 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.