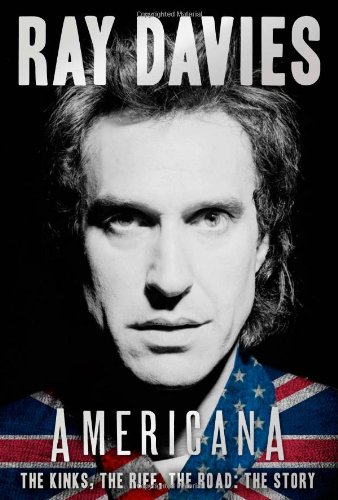

In Americana, legendary songwriter and Kinks cofounder Ray Davies tells the tale of how American culture, music and lifestyle, or “Americana,” has captured his imagination since his childhood and played a major role in both his career and personal life. Davies is the first to note the irony of the frontman for the most “British” of the British Invasion bands being so obsessed with the U.S., but he makes a persuasive argument for the importance America has held for him since the 1950s.

There is no listed co-author for Americana, and the book is written in a sardonic, world-weary, yet somehow still hopeful voice that fans of Davies’ songs will recognize. Davies freely admits he is an often cranky loner who would rather observe life as fodder for his songwriting than directly engage in it, and as a result the reader gets a keenly observed but slightly detached look at how a working-class lad from the Muswell Hill neighborhood of North London turned his boyhood fascination with all things American into a decades-long career as a global rock star.

The book jumps around chronologically quite a bit, which at times can be confusing and frustrating for the reader. It begins in New Orleans in 2002, with the unspoken specter of Davies’ near death experience in that city when he was shot resisting a 2004 mugging hovering over the proceedings. While Davies does a good job of describing the twin feelings of impending doom and irresistible appeal New Orleans held for him as the most American of cities (it’s a giant mixture of all ethnicities, traditions and cultures), his detailed account of his frequent travels to New Orleans quickly turns dull and stays that way until the mugging and its aftermath, which is retold in vivid detail that pulls the reader right into an intense, life-or-death situation.

Fortunately, Davies also frequently delves into the story of The Kinks, with a focus on how conquering America like their predecessors the Beatles and Rolling Stones was always a primary goal. Davies entertainingly relates how unlike the carefully promoted Beatles and Stones, The Kinks were unleashed on America with no preparation or crafted image, with disastrous results that led to the group being banned in the U.S. for four years for reasons Davies is still not entirely clear about.

The Kinks chapters are the best part of the book. The reader gets to experience a first-hand, intimate look at how The Kinks took their uniquely British sensibility back to America in the 1970s, once the performing ban was lifted, and go on to become one of the most successful arena rock bands of the 1970s and 1980s. There is a lot less “sex, drugs and rock and roll” than many other rock memoirs, but Davies pulls the veil on many of the more mundane details of rock stardom that still remain interesting.

Toward the end of the book, Davies gives a frank account of getting shot by a mugger in a New Orleans alley, entering a local hospital as an anonymous stranger and leaving as a global celebrity, and then undergoing a grueling rehab. In addition to providing palpable, raw emotion, this section of Americana also offers an eerie parallel to Davies’ experience getting banned from performing in the U.S. for reasons he didn’t understand.

Davies comes right out and says he thinks the New Orleans justice system purposely made him continually return to the U.S. at inconvenient times to provide testimony so the charges against his assailant would eventually be dropped (as they were in 2007), due to fears the publicity of a conviction would harm tourism. He also floats the theory that he was the victim of an attempted assassination, although he is less convinced.

America is the country that both gave Davies his greatest success and also almost killed him, and those polar extremes sum up the essence of Americana. Davies does not unconditionally love America, but he is unconditionally drawn to it and has spent his life both in its shadow and shining down on it.

No Comments comments associated with this post