Royal Potato Family

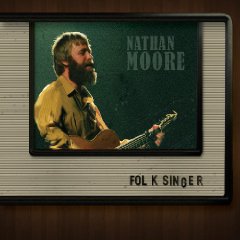

It’s easy to imagine Nathan Moore traveling the country circa 1933, singing to the plight of the working man suffering cruelly at the hands of the Great Depression. It’s also easy to imagine Moore filling college auditoriums circa 1965, crying out for peace in an escalating war. And so, ironically, it becomes hard to imagine Moore’s music fitting in today, where substantive, topical messages are often forsaken in the quest for a market friendly, innocuous image. But that, paradoxically, is what makes Folk Singer a truly great album. Here, it’s all about what’s being said, not who’s saying it.

In the face of a society in which dreams are the greatest single export, it’s utterly satisfying to hear an album awash in ponderings on the alienation that comes when those dreams go unfulfilled. In “Everybody Dreams,” Moore sings “Everybody dreams, but everybody can’t win the lottery, nor sometimes it seems we just got to be, fine watching through a window pain.” This bracing, unnerving candor is pervasive, grounding it with an inherently anti-pop realism. Even in the most fanciful of all of music’s flights, the love song, Moore refuses to deal with anything less then reality, as in “Invisible Guy,” where Moore painfully contemplates being overlooked by a love interest.

Reminiscent of Bob Dylan and Tom Waits, Moore, unaccompanied, plays acoustic guitar and harmonica while singing his message. This simple song structure further focuses listener attention wholly onto lyrics, which Moore resoundingly delivers. His gruff baritone croons in “Hard Times,” “More hard times, ain’t just some old folksong, hard times is still going on,” reflecting on modern day injustices. The most poignant passage – a description of a food line where a young man with a minimum wage job stands beside a soon to be retiree, who just got laid off – seems rather fitting these days, and makes for a truly sobering listening experience.

Throughout the eight songs, musical backing behaves more as atmosphere, rather then a great point of interest in it of itself. Though a few harmonica solos and acoustic flourishes stand out, particularly in “All I Can Do Is Dance,” even with a discerning ear, it’s difficult to pinpoint a great exploration of either instrument, however, that’s perhaps the way it should be. The greatest hallmark of this album is its simplicity which drives home lyrics precisely because of their plain surroundings. Displays of instrumental prowess would only work to dismantle the quintessential folk vibe dripping throughout the album. Like Dylan, Moore’s voice is unmistakably his primary instrument.

At first pass, listeners may be quick to judge this album as too bare, with too little going on, but Folk Singer works exactly because of this. Moore effectively rolls life back down to a time, a cerebral plane, where only subjects core to the human experience exist. Void of the shiny production and flashy displays so common in modern acoustic music, this becomes a folk album by a folk singer, in the truest sense. Here, image ceases to matter, only the words gets through, and Moore’s greatest power lies in his refusal to retreat when things get uncomfortable, opting, rather, to dive head first into reality.

No Comments comments associated with this post