Gnomonsong

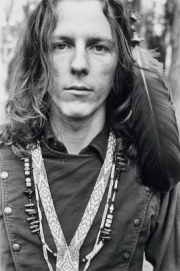

Sometimes someone hits you at the right moment with something so real it wakes you up. You can’t quite explain what makes it feel so right, it just is. Case in point, Michael Hurley’s new release Ida Con Snock. There is a pleasant familiarity to his soft iconoclastic country folk tunes that are neither derivative nor deceptive. Perhaps it is the fact that the album was recorded at Levon Helm’s Woodstock studio. Perhaps it is the early morning residue of some cool fall breeze of contentment. Perhaps, it just soars.

There is a relaxed, easy stroll-through-the-woods feel to these tracks, carried forth from some ancient Appalachian place that is very much brought into the moment. Whereas Hurley occasionally ambles amiably into blues mosaics (“I Can’t Help Myself”) and melancholic ruminations (“Wildegeeses”), he binds most of his thematic spine firmly with his stock-in-trade: country folk fringe embedded within confessional tales. “Valley of Tears” is a gentle serenade, “Going Steady,” a gorgeous lullaby, “Hoot Owls” a gangly shuffle, while ancient portraits are given a new haunting frame (“Loch Lomond/Molly Malone”), and two-steps are offered and exchanged (“Ragg Mopp”). Finally, complex acoustic guitar patterns are layered into simplistic bliss (“Any Ninny Any”).

Old and battered fall hats should be nodded towards Hurley’s accompaniment, as well, on Ida Con Snock. With Hurley is Matt Cooper on steel guitar, Jean Cook on violin, Ruth Keating, drums, Dan Littleton, vocals and harmonium, Karla Schickele, bass and vocals, and Tara Jane O’Neil, the ‘hoot-howl’ background vocals on “Hoot Owls,” a playful…uh, hoot to a not so bygone feathered Buddha. All, throughout the audio miles traveled, help Hurley along on this delightfully mellow 12-song adventure.

Rolling slowly, confidentially, wistfully forward, Hurley and his band transforms the listener, and the past becomes present. Singer/songwriter/guitarist/violaist/Wurlitzed wizard is either looking back with seasoned wisdom, or eyeing the future without a tinge of regret (“I Stole the Right to Live”). I can’t quite figure that one out, and I think that is Hurley’s true gift—he stays young, spins a profound yarn or twelve, while never forgetting that all of that heady baggage was accumulated over many years, many journeys of experience, seeking that next fascinating turn around the bend.

And when you’re searching for that next high note, seeking the innovation that will propel you forward—to find something/someone new—sometimes you just need to listen to the low notes that drift by, resting upon you, soothing the weary mind, and finding a way, without even trying, really, to make an impression. Hurley does, indeed, here.

No Comments comments associated with this post