Rhino

Not so long ago, music journalism had considerably more perks, from press junkets to backstage passes to armloads of posters, vinyl records, t-shirts and other band-related swag. Today, virtually all record labels try to save money by limiting their “kindness” to writers to free albums and complimentary concert tickets—which are really the two basic tools, along with interviews, necessary to do labels the favor of covering their artists in the first place. Most record companies now go further still in their quest for frugality, demanding that writers download free mp3s of new albums rather than request hard copies, which would incur shipping costs. Music writers never really lived luxurious lives, but now rather than sit at the back of the bus, we’re not even on the bus.

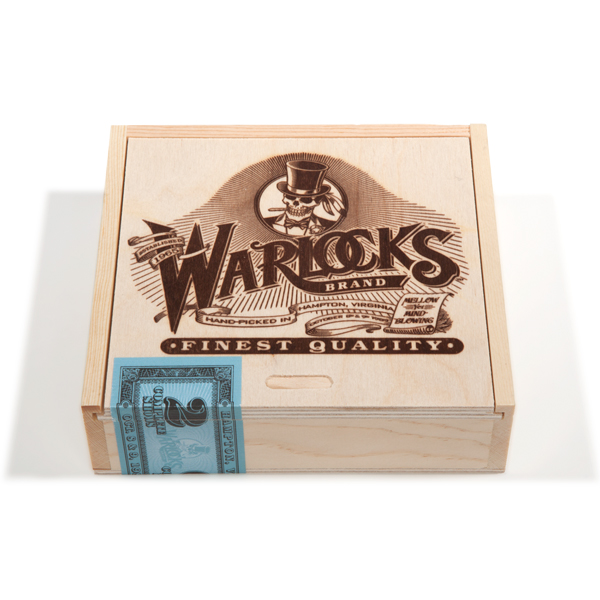

Rhino, however, is still doing at least an adequate job of helping writers hitchhike their way toward writing reviews with pleasure. Just the other day, I received a review copy of what has to be the most beautifully packaged set of music produced in recent memory, the Grateful Dead’s long-awaited Formerly the Warlocks boxed set.

As the story goes, by the late 1980s the Dead’s traveling fanbase had grown so immense that the group had two options as a touring band: play massive 70,000-capacity football stadiums or perform multiple nights at 20,000-seat hockey arenas. Otherwise, the thousands of Deadheads who followed the ’60s holdovers around from town to town as a way of life would combine with hard-partying local weekend warriors to create a sincerely dangerous scene—and the band would be banned from yet another town or venue.

Another option would’ve been to take a year or two off from performing together at all, which the Grateful Dead never did in 30 years together between 1965-1995. This would’ve not encouraged the religiously hardcore Dead Heads slip into some kind of normal life and pushed the band’s management to develop safe and successful ways for the Grateful Dead and its fans to enjoy more intimate concerts. It also would’ve most likely saved heroin-addicted frontman Jerry Garcia’s life.

Regardless, the Grateful Dead never did take a real break from touring, other than a good part of 1975. Packing mega-venues like Soldier Field and Oakland Coliseum was the ironically lyric-heavy jamband’s career until Garcia’s death in 1995, despite the troubled singer-guitarist’s complaints in business meetings that playing stadiums was a drag. But a couple times in their latter years, the Dead and its management found two ways to leave its traveling legion of hippies, with which they had a love/hate relationship, in the rear-view mirror: book concerts well out of driving range from each other or, in the case of the two Hampton concerts in 1989, perform under another band name.

Yup, in October 1989 the marquee outside Hampton Coliseum read—above “Oct. 10-15: Walt Disney’s World On Ice”—“Oct. 8-9: The Warlocks.” Back in the mid-’60s, when the Grateful Dead made its start serving as house band for writer/fugitive Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests, the San Francisco psychedelic blues band had been known as the Warlocks. So for their October 1989 concerts in Virginia, the Dead booked Hampton Coliseum as the Warlocks and did its best to only sell tickets to residents of Hampton and a few lucky insiders. Sure, word got out and a good number of traveling Dead Heads came to town, but the chaos that would’ve been associated with the Dead, in the height of its popularity, playing such a small town was averted. And those able to get in enjoyed some unforgettable treats the band planned just for Hampton.

For starters, the band broke from tradition by actually rehearsing together, which, on October 8, produced a refined version of “Help On the Way > Slipknot! > Franklin’s Tower,” a dynamic suite (from the 1975 album Blues For Allah) which had not been performed in four years. The first high-energy Hampton concert culminated in “Morning Dew,” a poignant nuclear-war ballad included on the Dead’s eponymous 1967 debut LP, and it was as good a version of “Morning Dew” as the band played in its final decade together. For a bunch of guys approaching their 50s, the Dead was on in Hampton.

Still, despite the excitement that still surrounds these stealth shows to this day, only a few selections from each night stand up to 21 years of perspective. Like virtually every other Dead show from the polarizing group’s last 20 or so years together, both Hampton concerts followed a formula: Start the first set with a rocker; continue with some slow blues, a couple of rollicking country songs, maybe a Dylan cover, and an old-timey Dead classic such as “Row Jimmy”; finish the set with an bright and exciting (but not too exciting) psychedelic burst like “Bird Song,” which foreshadows the heavier improvisation in the second set. Then, start the second set with a big classic like “Playin’ in the Band,” eventually delve into total free-form instrumental mayhem in the middle of the second set, return the audience to its senses with a morality tale, maybe “Stella Blue” or “Wharf Rat,” and then finish with a show-stopper like “Lovelight” or “Good Lovin’.”

As legend has it, the Dead played formulaic concerts to coincide with the emotional progression of LSD trips, originally taken by everyone involved—from band and its stage crew to the audience—and, later, mostly the audience. That’s at least moderately understandable. But I’ve never taken LSD while listening to the Grateful Dead. And as a lover of improvisational music, and someone who initially was attracted to the Grateful Dead because of the oft-heard statement “no two Dead shows are alike,” I’ve come to generally skip listening to the first sets of their recorded concerts entirely, sink my proverbial teeth into the meat of the band’s more musically powerful second sets, skip the cheesy oldie-finales and listen to exceptional encores when they exist.

In the case of October 9, 1989, the meat of the seamless second set happens to contain some of the most memorable music the Grateful Dead ever performed. From a solid “Playin’ in the Band” to a gorgeous “Uncle John’s Band” and back to the coda of “Playin’,” the Dead played capably, and even mightily, as a unit—something that was hard to come by in the aging group’s latter years, when each band member literally had his own tour bus and “jamming” most often meant six musicians soloing at the same time, their individual noodling rarely taking into account the presence of the five other men on stage.

Even better, before the final notes of “Playin’ in the Band” had even been given a chance to ring out, Garcia giddily strummed the opening notes to “Dark Star,” the Grateful Dead’s signature tune—and one that hadn’t been performed live in over five years. Soon the entire band kicks in, at which point “Dark Star” is met with the most enthused audience response I’ve ever heard on record. And it’s a startlingly crisp, confident and beautiful “Dark Star.” Gradually, the music seems to not just recall the Dead’s previous musical peak (the 1969-70 Live/Dead period) but also impressively find itself updated to incorporate Pat Metheny-style ’80s fusion and tastefully nefarious use of MIDI technology. Whereas on Live/Dead we hear a young, virtuosic and acid-washed Garcia blessing the Fillmore with an incredible succession of fresh ideas within the form of “Dark Star” with just a stock Gibson SG, on Formerly the Warlocks MIDI allows the guitarist to improvise melodies as a trumpet, bassoon, kalimba, or whatever.

“Reason tatters / the forces tear loose from the axis,” Garcia sang at the second Hampton show before the Dead descended into 30 minutes of truly dark and demented Sonic Youth-esque instrumental madness out of “Dark Star.” After the instrumental terror subsided—and, here in 2010, I had taken our infant daughter out of the room to protect her budding sanity—Garcia speak-sang “Death don’t have no mercy in this land.” So much for the Dead being a happy, rainbow-eyed bunch of hippies. If you’re a young neo-hippie and can get through the Hampton “Dark Star” set alive, I highly suggest checking out “Expressway to Yr. Skull” and “Diamond Sea,” Sonic Youth’s own platforms for enlightened psychedelic guitar-horror, because the happy-go-lucky banality of supposed Dead-successors like the String Cheese Incident just doesn’t delve this deep sonically.

In the end, however, despite the experimental burst “Dark Star” brilliance and the inclusion of other long-unplayed classics like “Attics of My Life,” the Hampton concerts were memorable but, in all, not so musically exceptional. In several very rudimentary rock ’n’ roll songs, including “Throwing Stones” and “Good Lovin’,” the group’s two drummers quite amateurishly lose the beat entirely and then pick it up at a different pace. And “jamming” songs together generally means that Garcia begins playing an introductory line from a different song regardless of what key it’s in or whether the rest of the band is aware of his intent.

At times, when performing wedding-band standards like “Gimme Some Lovin’” and “Good Lovin’”—oldies Richard Simmons would be glad to sweat to—the Dead just sounds over the hill. That the group would play together for six more years repeatedly seems impossible on these six discs, especially now that we know that keyboardist/vocalist Brent Mydland—the relatively youthful talent behind the Dead’s late-’80s musical renaissance—would be dead of a drug overdose less than a year after the “Formerly the Warlocks” shows.

Most important, scattered (but sustained) moments from this new collection highlight a very successful yet very troubled group of middle-aged musicians jelling in a way they rarely did in their final years together. A disc or two from these six might adequately represent the best live music of the Dead’s final 15 years together, but I surely don’t possess the kind of encyclopedic knowledge of the Grateful Dead’s performances to know for sure.

What I do know is that Formerly the Warlocks contains some incredible music in an utterly gorgeous package. Inside a wooden box with a Warlocks logo burned onto it includes six discs, a ticket from each show, a Blair Jackson essay spanning six photo postcards from the show, a Hampton Coliseum postcard with the first night’s setlist on the back, an original Charlotte Observer newspaper article from 1989, a Halloween-themed button from the shows, and an informational 1989 handout from the management to Dead Heads, explaining that “if you do not have a ticket, you will not be allowed in the parking lot” and pitching tents and vending outside the concerts would “jeopardize their ability to play in the future.”

Kudos, Rhino. And thank you.

The only question I have is: When does the Grateful Dead effectively go out of business? The group’s mostly mediocre studio albums don’t really sell and, as the Dead broke up 15 years ago, there are only so many great live recordings that can be released. Plus, in time the number of people who can even say they knew someone who saw the Dead perform will dwindle to zero. One has to wonder if ours will someday be a world without new Grateful Dead releases and/or a world without Dead Heads.

No Comments comments associated with this post