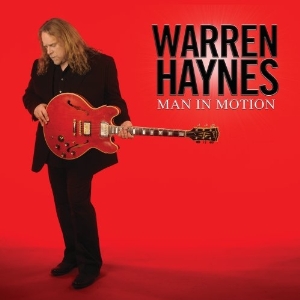

Stax

“Still life is overrated,” sings Warren Haynes on the title cut of his new solo masterpiece Man In Motion. “Still life”? Really, Warren? What would you know about “still life,” man? It’s fitting that Haynes lists the late, great James Brown as one of his soul music heroes – ol’ JB may have held the title of “The Hardest-Working Man In Show Business” in his day, but there ain’t many flies on Mr. Haynes, either. Start totaling up an average year’s worth of gigs between the Allman Brothers and Gov’t Mule, plus countless live and studio guest spots – figure in some travel time and a few minutes for things like breathing, chewing, and kissing wife Stef Scamardo hello/good-bye and you tell me: “still life”? Right …

Luckily for all of us, Haynes somehow not only found the time to go into Willie Nelson’s Pedernales Studios to record a new solo disc – Man In Motion was banged out in a six-day burst of creativity – he also managed to bring together a true Dream Team of soul and funk to help him in his efforts. Check out this core lineup: bassist George Porter, Jr.; Ruthie Foster on background vocals; Raymond Weber on drums; tenor saxmaster Ron Holloway; and the keyboard talents of Ivan Neville and Ian “Mac” McLagen. And guess what, boys and girls: the music sounds as great as the line-up.

Man In Motion finds Haynes paying homage to the soul and blues albums he loved as a kid – and the genre is a fine fit. The fact of the matter is, as talented a singer/songwriter/guitarist as Haynes is, there are times when his work with the Mule can get pretty dark. Real as hell – but dark. The ever-present R&B vibe on Man In Motion shines a light on the most soul-baring of moments; there’s no lack of power or honest ache … but there’s always a light of hope, as well.

Add it all together, and you have one hell of a piece of work – a textbook example of how to build a great album, actually.

For instance …

Open with some drama: Dig the first few seconds of the title cut: big, beautiful piano chords by Ian McLagen while George Porter, Jr. pedals on a single, deeply-burbling note. Ivan Neville begins fading in a suspended chord on the organ as Haynes’ muted wah guitar mutters to itself. Seriously – ten seconds into “Man In Motion”, you just know something amazing is about to happen. And it does.

Look ‘em in the eye: We can all come up with examples of brilliant studio work that was done in shifts with various players’ parts layed down at different times – or brought in from other continents, for that matter. But nothing – nothing – compares with the vibe created by musicians huddled together in the studio, acting and reacting, feeding each other ideas with the absolute confidence that the road is going to lead somewhere good without having a map at hand. Haynes and producer Gordie Johnson know that; and that vibe is what you feel all through Man In Motion.

We talked about the opening moments of the title track; let’s move ahead to just shy of the four-minute mark. Haynes belts out the final chorus and lets the powerful Grooveline Horns (Carlos Sosa on sax; Fernando Zastillo on trumpet; and Reggie Watkins on trombone) punch out a groove before he steps back in, firing off blasts of Gibsonese at them. They answer back; ideas are exchanged; then everybody lays out, leaving just the drums and some funkynasty keys chawing away. Fade out? No way – that big ol’ fat B3 coaxes everybody back into it and – WHAM – they’re off and going again. Haynes tickles the strings; he grabs a fistful and yanks; he pushes things up as far as he can reach, then lets them tumble back down. In the meantime, the horns lean right back at him; and the keys swell up from beneath and help suspend it all. This sounds this way because that sounded that way – the vibe feeds itself, encouraged by a roomful of talent listening to each other.

It’s all about the tone: Haynes’ guitar playing is gorgeous on Man In Motion, employing the thick, sweet tone of some vintage Gibson hollow bodies for much of the album, with some King-inspired (B.B., Freddie, and Albert) approaches to the matters at hand. The combination at times sounds like honey-slathered bee stings (“Take A Bullet”, which features David Grissom on rhythm guitar), while other moments are almost Hendrixian jazz (the closing moments of the album’s sole cover tune, “Every Day Will Be Like A Holiday”). And there are songs like “Hattiesburg Hustle” (with co-producer Johnson sitting in on rhythm guitar) where Haynes’ playing is as raunchy and righteous as anything he’s ever layed down.

A house of soul is only as strong as its foundation: I know that drummer Raymond Weber and bassist George Porter, Jr. have played together as members of the all-star New Orleans Social Club, but if you told me that they’d been playing together since birth, I’d believe you. I mean, listen to them on Man In Motion and you tell me: from the dark slink of “River’s Gonna Rise” to the rubbery funk of “On A Real Lonely Night”, the pair of them moves in total groove tandem as if they’ve been doing it for years and years.

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition: It would be fair to say that what Warren Haynes is to the guitar, Ron Holloway is to the tenor sax. The fact that two such big guns can go head-to-head without overplaying or tripping over egos is a measure of the respect they have for each other. Consider the closing minutes of “Sick Of My Shadow”, where after bouncing licks off each other in an ever-tightening circle, Haynes and Holloway link up in a series of slurs that make their way up the scale, culminating in a crazy cascade of wails and bends. The only downside is that the cut fades at that point. Maybe everything went to pieces after that, but it sure sounded like they were still cooking. Bottom line: when a just-shy-of-seven-minutes-long tune feels like it got cut short, it was a pretty damn good jam, boys and girls.

Or how about the slow sway of “Your Wildest Dreams”: Neville and McLagen build a lush pulpit of keyboards for Haynes to do some serious testifying until the sax enters, picking up on the spirit of Haynes’ vocal. Holloway blows like a broken-hearted wild man, pounding the ache into a pulp as he works his way up into a Martin Fierro-style upper-range bellow at the end. Heart finally wrung out, Holloway steps back to let one final breath of the organ bring things to a close.

Behind every good man …: Haynes’ choice of Ruthie Foster on backing vocals was a wise one. Foster can lay into the sound canvas with a big ol’ barn brush, or she can add accents here and there with deft dabs of soulfulness. Check out her weave with Haynes’ guitar during the final couple minutes of “River’s Gonna Rise” – her Merry Clayton-like delivery matches everything Haynes can throw her way and then some.

How to bring the curtain down: The album-closing “Save Me” finds Haynes embraced by McLagen’s lush piano and big, billowing waves of sound from Neville’s organ. It’s a lovely arrangement – stark, yet full at the same time – allowing Haynes to just draw off and let it fly vocally. A little over four minutes in, the song reaches its conclusion and we have a few moments to reflect before the keys return with just the voice of Haynes’ Gibson nestled between them. This might just be one of the most beautiful outros since the piano coda on “Layla”.

From his early days with David Allen Coe to his current status as the go-to guitarist in the world of jam, Warren Haynes has done it all: from picking outlaw country gee-tar to leading missions into the psychedelic unknown. But as much of a natural as he’s been in the various musical worlds he’s traveled, the role of soul man may actually fit Haynes the best of all.

Welcome home, Warren.

No Comments comments associated with this post