Now virtually a recluse except for the odd appearance such as that at the 2006 Grammys, Sly Stone may be the most magnificent enigma modern pop music has ever produced. Under the name of Sylvester Stewart, he cut his teeth as a musician and producer as well as a disc jockey in San Francisco at just the time the melting pot of eclectic sounds was beginning to bubble. Assembling the Family Stone, he forged a style incorporating (mainly but not limited to) rock, funk and pop that was, at a time of social turbulence mirrored in the music, as thought provoking as it was effervescent.

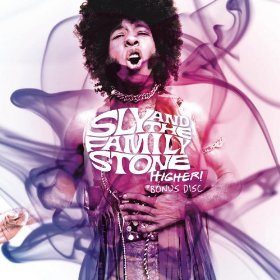

The long-awaited and much delayed four-cd anthology Higher chronicles Sly and The Family Stone’s progression from infectious dancemeisters to cultural icons and in so doing documents how, from the very earliest days of Sly’s work on his own and with brother Freddie, their ambitions were almost as fully formed as their chosen style(s).

The progression of tracks on disc one of Higher is the aural equivalent of watching time-elapsed photography. The progressive (in every sense of that word) addition of voices and instruments, including horns, is designed to reach and touch a pleasure center, the combination of which sensations hit the musicians almost as deeply as the listeners. The resulting euphoria reached its apogee with Sly and The Family Stone’s performance at Woodstock 1969: in retrospect, the group’s appearance at the festival seems a logical, almost inevitable, culmination of their career progression to that point.

Successive album releases combined with popularity of their release of singles such as “Sing A Simple Song,” thereby priming a pump of response that overflowed at the near-mythic festival. Sly & Co remain the single most memorable moment of the iconic event this side of Jimi Hendrix, all the more significant consider the racial implications of two African-American musicians s wholly capturing the fancy and loyalty of largely upper middle class Caucasian kids.

Hearing the infectious child-like charm Sly could radiate, the melody line of “Frere Jacques” underpinning “Underdog” long before “Everyday People” and “Stand” became anthems almost on par with “(I Want to Take You) Higher“ is a means to understand not only the complexity of his work, but the seemingly effortless way he fused idea and action. The creative packaging of the four cd’s and booklet within the 9.5”x10”x.24” box inserts reflects the colorful music it encloses, but in addition, points to the circular patterns of musical cycles, technological and otherwise: early tracks in monaural sound, such as “Scat Swim” and “Buttermilk,” make for ideal listening in digital form on companion devices. It’s perfectly appropriate too that the clarity of remastered stereo sound appears at the very time the band’s style crystallizes on tracks like “M’ Lady.”

So it’s a measure of the depth to which Sly and the Family Stone inspired musicians, men and women, to this day (remember The Family was integrated in more ways than, one no small revolutionary act at its time) that the story told by Higher is one that continues to connect some half-century after the man first began recording the year The Beatles first came to America, 1964.

It’s tempting to look at this descendant of James Brown and Otis Redding, contemporary of Hendrix and Stevie wonder and forebear of Prince and The Roots, as something of a shooting star given his relative fall from grace as represented by There’s A Riot Goin’ On yet that 1971 album was as vivid reflection of its time as “Dance to the Music” and “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” though its turgid likes remains in perspective within this box set via “Family Affair.” The dynamics of Sly Stones career were those of his music: the best known tunes of his discography don’t appear here till disc three, but the level of interest remains comparably high through the two discs that precede it and on the one that succeeds it, illustrating how fascinating a figure was Sly then…and now.

The 1970 Isle of Wight festival appearance reaffirmed the impression he left by his explosive concert the previous year in upper New York state, these previously unreleased recordings of which are among the most rare of the seventeen among the total of seventy-seven here. Still, the detailed timeline included in Higher, courtesy of Dutch authorities Edwin & Arno Konings, affords the expanse of the music its proper emphasis just as does biographer Jeff Kaliss’ essay. Ultimately, the most important statement this package carries may very well be that Sly and the Family Stone had legitimate claim to their celebrity because, at its best, their work resonated with the broadest possible audience.

No Comments comments associated with this post