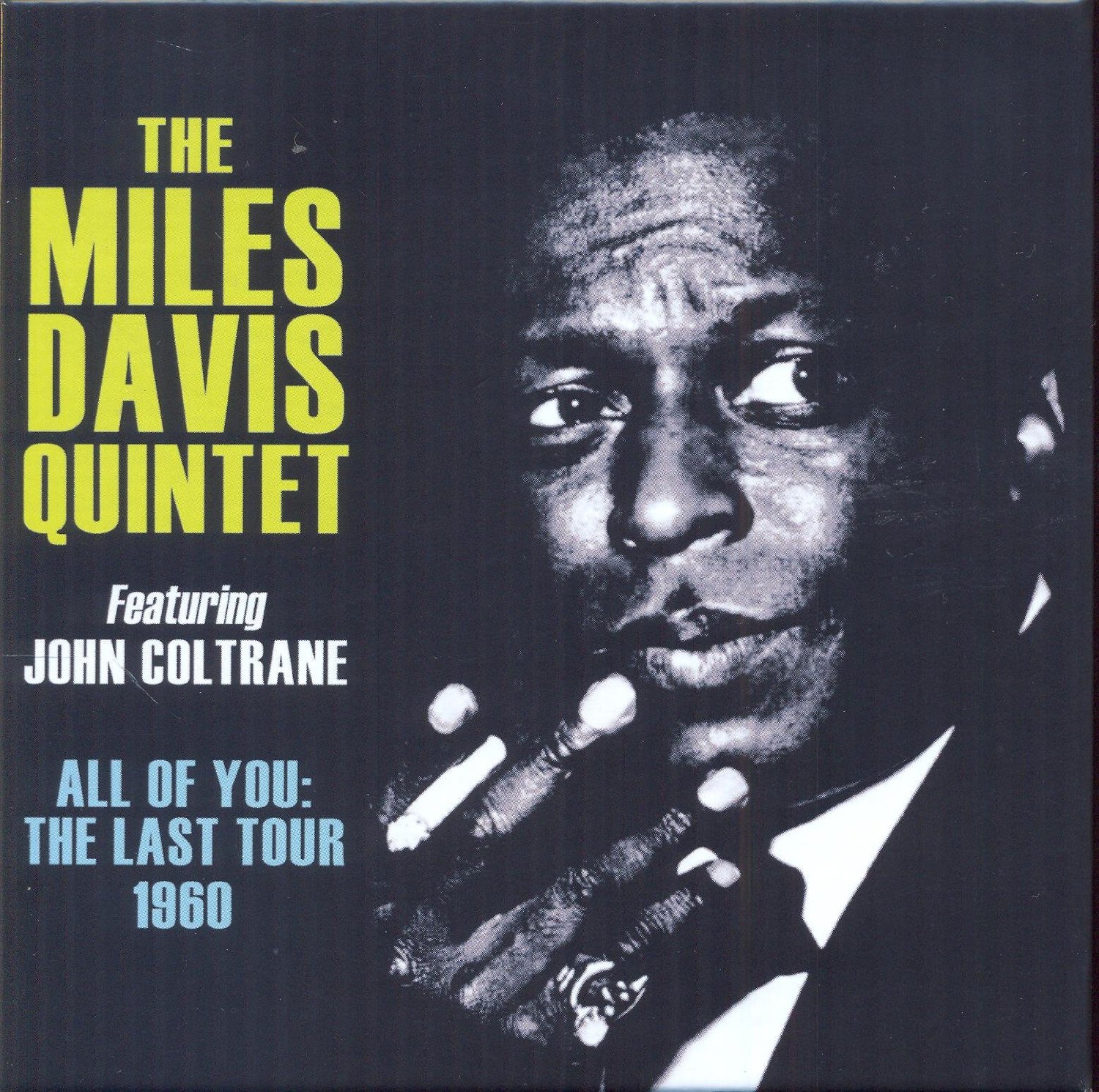

Earlier in 2014 The Allman Brothers Band issued The 1971 Fillmore East Recordings, a box set of three nights of concerts from the New York City venue that initially produced the band’s landmark At Fillmore East. Known for wondrous flights of improvisation led by the twin guitars of the late Duane Allman and Dickey Betts, the group was seen as a groundbreaking force in rock and roll, yet the roots of such performances lied not only in the deep blues of the South, but also, as the Allman and Betts had often stated, in the music of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and the seminal 1959 album Kind of Blue. With fortuitous timing, then, comes The Miles Davis Quintet featuring John Coltrane All of You: The Last Tour 1960, a four-disc collection comprised of performances from eight European concerts, assembled from radio broadcasts as well as private recordings, that represent many of the final appearances of this legendary five.

Supporting Kind of Blue, the repertoire is, as expected, heavy on renditions from that album, as well as ‘57’s Walkin’ and ‘Round About Midnight and ‘58’s Jazz Track. While there are recurrences throughout the four discs, given that these compositions were built with an ear toward extended improvisation, each is unique within the evening itself. The March 21st First and Second House entries, divided by a rather curious and illuminating Coltrane interview with Swedish journalist Carl-Eric Lindgren, contain versions of “So What” that are a representative example of this cleaned slate approach the band employed from night to night, with the structure of the song kept mainly intact, yet the soloing reflective of the moment, irrespective of the performance given hours earlier.

Coltrane is fascinating in this regard, offering a furiously aggressive run in the Second House version, perhaps responding, slyly, to Lindgren’s assertion in the intermission that Trane’s critics said he was playing angry. When examined with a wider lens, using “So What” as a focal point, the eight renditions contained within, as well true of the other seventeen tracks, are colored as equally by drummer Jimmy Cobb’s directive tempos, by Paul Chambers strutting bass lines, by Wynton Kelly’s contrast or solidarity on piano, and of course Davis, himself, whose trumpet speaks provocatively in turns of modal minimalism, post-bop optimism, and select moments of pause and reflection, as much as they are vehicles for Coltrane’s expansive musings. A group dynamic in the throes of near-perfection, through telekinetic shifts in mood and conversation, every note chosen with impeccable, constructive, and immediate intention, the Davis Quintet bears in name only unembellished connotation.

Drawn from shows in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Frankfurt, Munich, Zurich, and Scheveningen, the sonic quality varies only slightly between warm and rounded to thinner and brighter recordings, (only the March 30th Frankfurt outing is conspicuously lesser in fidelity), all have undergone a cleaning and remastering that have rendered them as uniform in appearance as possible. Scattered releases, and countless bootlegs, of these shows have existed across the globe for years, but now have been gathered and presented together officially for the first time. Additionally, a thoughtful and comprehensive 30-page essay written by saxophonist Simon Spillett detailing the chronology leading up to the tour, the individual performances, and brief epilogue provides an admiring and supportive backdrop supplementary to the music.

The effect and influence of the Davis and Coltrane partnership is immeasurable, and hindsight does nothing but add value to these recordings. The Quintet of 1960 expanded the scope of what was imaginable inside and outside the often protective genre walls of jazz, writing new definitions of form and content in improvisation, and creating a philosophy that endures as a touchstone today. Regrettably, it also marked a pinnacle never to be reached again as a unit, as the Davis Quintet with Coltrane would dissolve following this tour. Only the music, a most beautiful, daring, progressive, and essential music, remains, and how lucky it is that it does.

No Comments comments associated with this post