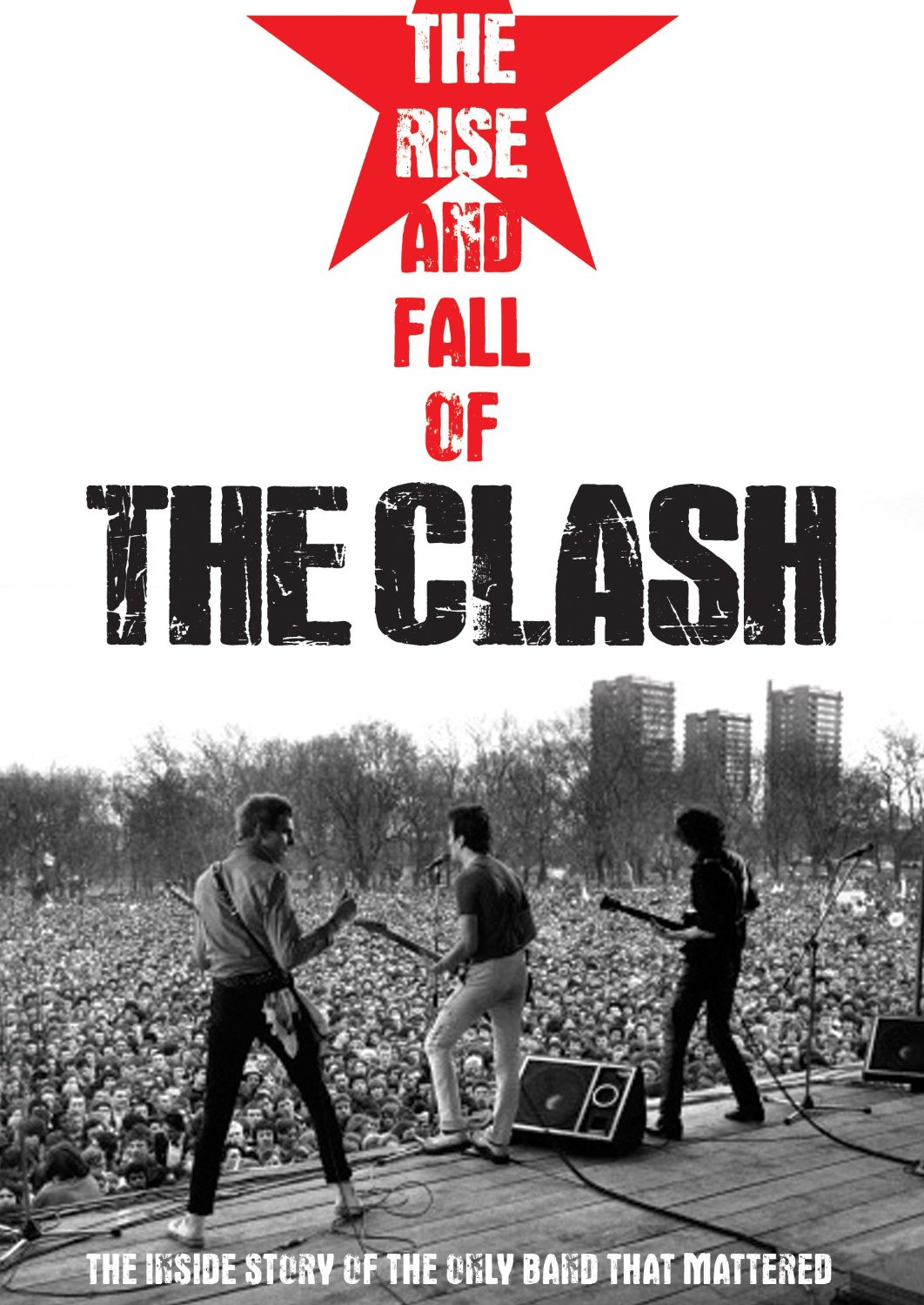

The Rise and Fall of The Clash is just that; the rise and fall of the British punk outfit that for a half-decade in the late 1970s became by its own prophecy, ‘the only band that mattered,’ only to have it all disintegrate into a disowned final album and a caricature of itself. The Clash’s time at the top was brief, long enough for a legacy cemented, but unfortunately the quartet’s position of influence and success could not be sustained. Driven by the internal squabbles of its members over drug abuse- in guitarist Mick Jones’ case a hypocritical charge of too much pot from leader Joe Strummer, and the sad heroin spiral of drummer Nicky ‘Topper’ Headon- as well as the actions of manager Bernard Rhodes, cast here if not in fact certainly on film, as the central villain of the saga.

The problem with the continuous stream of anecdotes and accusations aimed at fingering Rhodes for much of what went wrong is not in whether or not these are true, but rather the lack of response from Rhodes, himself. The film spends a large amount of its energy with various participants in the band’s inner circle detailing Rhodes’ failings, yet has only a short patch of rough audio serving as a defense for the man. Additionally the one, maybe two fleeting, grainy images of a seated Rhodes at work are used whenever he’s referenced, to exhaustion. It’s likely that Rhodes declined an opportunity to represent himself, and left director Danny Garcia with little choice but to recycle. That lack of material, given the number of times Rhodes is spoken of, leads to a palpable, if not justified, redundancy with regard to his role in the group’s expiration.

Less so the portrayal of Jones, whose present-day interview appearances and apparent emotional reconciliation with that period of his life deliver much-needed humor and perspective into the proceedings. It isn’t whether or not he’s comfortable with the how and why of his dismissal from the group, but rather that he’s accepted it and the fate of his career in the aftermath, and he’s still smiling. More unfortunate is the absence of Strummer to provide counterpoint, whose unexpected death in 2002 sealed away any reunion hopes that were floating about just prior to his passing, and would’ve at least been available to refute or enhance the accounts.

In what are maybe the most revealing and poignant interviews, post-Jones members Vince White and Pete Howard offer vulnerable insight. White’s tearful, raw nerve recollections of his stint in the final phase are checked by Howard’s quiet repose, but both are adept at stripping away the façade of being in The Clash for what it really was- a bitter, dying band pushed by commercial expectations and without Jones and Headon, the men they replaced on guitar and drums respectively, half of what made the band the only one that mattered in the first place.

Here the fall of The Clash was more of the story than the rise. The film does its best to corroborate its claims, expand its details, update its characters, and entertain and educate its audience while it chronicles the demise. There are times when it feels a bit like an extended episode of Behind the Music and follows a pattern all-too-familiar of that of a successful rock group. Egos, drugs, creative differences, and of course, money inhabit the list of causes, with the effect being another band’s headstone. Yet, The Rise and Fall of The Clash ultimately seems to want to identify the who more than the how and why, intent on exposing the people that built a band born of socialist undercurrents to a colossal commercial level, only to have those same people tear it apart.

No Comments comments associated with this post