Bob Weir says he likes to perform the occasional solo acoustic tour because it allows him the opportunity to get at the root of the song, to hear it “as I originally wrote it.” Thankfully, that means the audience gets to hear it this way too, stripped of the band flourishes and high amplification. In fact, Weir’s solo tour reasoning was evident immediately, as he opened his Celebrity Theatre concert with “Truckin’.”

In the solo acoustic form “Truckin’” sounded like a different song as it lumbered along as if under the heavy load of the familiar electric version. The song was bluesy and choppy in places—places usually filled in by other instruments—but that was the added charm. This could be a negative aspect in other groups, but not in the context of Weir and his known passion for experimentation.

“Me and My Uncle” was a little more straight-forward, a rowdy cowboy song with plenty of twang that would have sounded at home around the campfire. The number elicited a rousing audience response with the refrain: “I’m as honest as a Phoenix man can be.”

Weir then launched into the first of three Bob Dylan songs performed this evening. While all wonderful in their renditions, given the catalogue of Weir’s own material, one would have sufficed. Still, “She Belongs to Me” came across as raw and heartfelt with Weir’s vocals reaching deep into the emotion pool.

Weir then took a bluesy turn with “Big Bad Blues.” A rambling tale of a playing card—a one-eyed jack—found along the roadside, Weir’s gift of narrative kept the visual aspects flowing while the guitar tugged at the minor chords in everyone. The song flowed into a small jam at the end that morphed smoothly into Dylan’s “Desolation Row.” Again, the solo form brought out new depth and parable in the number, with Weir’s vocal shadings accentuating some lyrics while others slid gently past. Of the three Dylan songs, this was perhaps the most realized and well-worked (even when he forgot a few of the lyrics).

The RatDog catalogue was plucked for a pair of songs, beginning with a rollicking version of “Money for Gasoline” that had the mostly sit-down crowd shifting anxiously in their seats. “She Says” was then introduced with, “This is one I never conceived of playing on the acoustic guitar until I ran out of stuff to do.” The song actually worked exceedingly well acoustically, a little jerky in spots, but the clarity of Weir’s vocals—especially when he went for the high notes—made it special.

A raw, deep-down growling bluesy approach to “Good Morning Little School Girl,” picked the crowd up via Weir’s gritty vocals yelps and innuendo and led smoothly, with Weir wiping the sweat from his brow, into that third Dylan song, “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” Oddly, the crowd gave the biggest roar of the evening as this song began; odd because it wasn’t one of Weir’s compositions. Was it because he’s been performing the song better than Dylan has in recent years?

Wearing brown pants, white T-shirt and requisite Birkenstocks, Weir announced he was going to stand for the next song. Before doing so he explained how he came to befriend his future songwriting partner John Perry Barlow by traveling to Wyoming when he was 15 because “I thought it used to be a right romantic thing to be a cowboy. So I did that.” Indeed, Weir continued—he worked on the Barlow ranch, mucking stalls and throwing hay—but also planted the songwriting seeds. One such number was “Looks Like Rain.”

Weir’s solo rendition was beautiful. This version didn’t require the album version strings or Jerry Garcia’s gentle leads, and was in fact complete in this stripped down manner. The song’s essence was laid bare, and the emotion palpable as Weir pushed the highs or dropped to a whisper. “Throwing Stones” followed, closing out the set and, like “Truckin’” earlier, was a little chunky, but with a completely different feel than full band versions. And it was rowdy as well, with Weir gesturing and digging into the guitar while the crowd shouted out “Ashes to ashes, all fall down” as Weir bowed out.

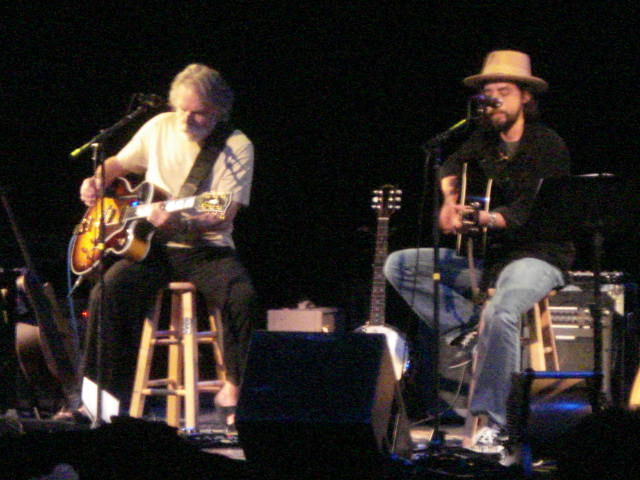

Weir returned with Jackie Greene in tow. Greene opened the show with a set that included Robert Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen,” a banjo and harmonica version of Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice (It’s Alright)” and several original numbers including “Tell Me Mama, Tell Me Right” and “Don’t Let The Devil Take Your Mind.” The duo made a formidable combo, with Weir on a vintage electric Gibson 335, and Greene on acoustic. The interplay was dynamic, cunning and well-conceived particularly on the opening “Shakedown Street,” perhaps the best version this reviewer has ever witnessed among the many. While Greene churned out the rhythm and handled lead vocals, Weir poked and jostled his wah-wah-fied electric into funky staccato spasms that alternately stuttered or seared. This rendering was heavy, dirty, gritty, funky, garage-y and dark in a manner that found the song’s core and exploited it to a bitter, glorious end, with a few choruses of “shake it down down” capping it off.

“He’s Gone” also captured that dark edge, with Weir jabbing out leads while alternating vocals with Greene. This bled into a bluesy/jazzy jam between the players. In true Dead fashion, Weir hinted with small frills at where the song was heading before rumbling into a completely psychedelic garage version of “The Other One.” A slow blues rendering of “Sugaree” followed with Greene handling vocals, which segued into a popping “Not Fade Away.” Weir’s biting solos over Greene’s harmonica playing powered the song into a few funky choruses of Delbert McClinton’s “Standing on Shaky Ground” before slipping back into Buddy Holly’s classic.

The crowd continued the “Love is Real, Not Fade Away” chant as the pair slipped off stage. There would be no more, but it was certainly more than satisfying enough. “We aim to please,” Weir said later, backstage. That he did.

No Comments comments associated with this post