Photo by Bud Fulginiti

Bob Weir takes his wife and kids to visit 710 Haight Ashbury. After the tour of the former Grateful Dead house, Weir’s daughters stare intently at two images on the sidewalk out front. One daughter says, “Hey. Neither of those guys are you.” And the other daughter – realizing the artwork is of Ron “Pigpen,” McKernan and Jerry Garcia – says “That’s because he’s not dead yet.”

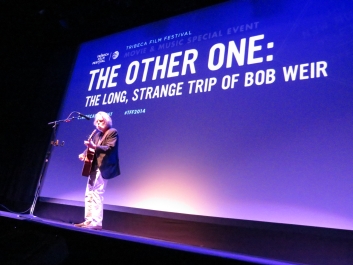

It is one of the many authentic moments during Mike Fleiss’ documentary, The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir, which made its debut at the Tribeca Film Festival.

The film provides an honest look into Weir’s unusual life and his transformation from a wild child to stardom to family man. Weir throughout the movie openly discusses being a misfit, having dyslexia, taking acid, joining the Merry Pranksters, dating women, being adopted, meeting his wife, becoming a father, reuniting with his birth parents and of course, his friendship with Jerry.

“I’ve been standing on stage and playing guitar more than any other human on earth,” Weir states in the beginning of the film, who played 2,318 shows as the rhythmic guitarist for the Grateful Dead from 1965 – 1995.

The documentary begins with snippets from a variety of musicians – Bruce Hornsby, Mike Gordon, Donna Jean Godchaux, Jorma Kaukonen, Perry Farrell, Jerry Harrison, and Sammy Hagar, who all agree Weir is the most under-appreciated guitarist on the planet.

The movie then shifts to Bobby’s childhood as we get insight from his sister Wendy about how her brother was the exception of the family. Weir was kicked out of preschool and a self-described “dedicated fuck up.” The movie explains that when he played music, it was the only time he was able to sit and focus.

The film also takes you back to the onetime location of Dana Morgan Music – which is now a bed store – where he first met Jerry. Weir retells how they hit it off instantly and went from a jug band to a rock n’ roll band, where they began playing topless clubs and at Ken Kesey’s acid tests. Weir explains playing on LSD, his awareness expanded and but also made him proficiently disoriented.

Fans also learn that Weir developed his unusual style from listening to pianists Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner records. He picked up how to add rhythmic-layered textured suggestions and how to add counterpoint suggestions, a skill he would do on a nightly basis playing alongside Jerry. One of Weir’s favorite tours was playing Egypt, where he said the backdrop of the Great Pyramids was a meeting of the past and present, and future.

We see images over time of Bobby on stage with his short shorts, snug T-shirt, and varying hairstyles. Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow makes the audience laugh when saying the Grateful Dead was “Bob Weir and the ugly brothers.” The living “ugly brothers” all make an appearance in the film: Phil Lesh, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann.

One of the most poignant moments of the movie is when Weir talks about the changes that took place during 1987 and how the focus shifted to Jerry. The movie brings up the ugliness of how crowd control became difficult, and how Jerry felt the burden of being idolized and began taking drugs (pot, cocaine and heroin) as an escape. Bobby admits without hesitation that he was Jerry’s bag man and just wanted to make his friend happy. “He knew I wouldn’t touch it because I was into a healthier lifestyle,” he said.

There are still many moments of bliss and happiness in the film: footage of Weir and Garcia scuba diving together during a family vacation, Weir and Garcia cracking jokes during an appearance on a 1981 episode of Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow Show, Weir reconnecting with his biological father – who never knew of Bob’s existence – and his father stating, “I walked away proud to be his dad,” and Bob finding love in his 40s with his wife Natascha Hunter.

Weir, who joined the Grateful Dead at 16, is 66. When he plays now, all he can think about is the pain in his right shoulder. But his love of music outweighs the pain. He sees it as a shared practice, a timeless genetic code that all ties together on stage.

Following the film, Weir, as expected, took the stage with guitar in-hand in front of a sold-out movie house for a live performance. His silvery hair was combed neatly, his gray bushy somewhat neatly trimmed beard and he sported a black jacket, black shirt, white pants and black shoes.

He began his hour acoustic set with an energized “Hell in a Bucket.” He voice strong and clear and his playing tight and textured – making it seem like another person was playing along with him. He followed up with strong renditions of “Peggy-O,” and “Black Throated Wind.” After three songs, Weir heated up, taking his jacket off to play “Loose Lucy,” “Corrina,” and “Masterpiece,” the latter which was the standout of those trio of songs. Then a familiar face to longtime Dead fans, Steve Kimock, joined Weir on stage and the music rose to an even higher level. Weir showed off his uncanny skill to add suggestions as well as add counterpoints to someone else’s playing. They ran through popular Dead tunes and covers beginning with “Playin’ in the Band,” that included an “Uncle John’s Band,” tease, Little Feat’s “Easy to Slip,” “Playin’ in the Band,” reprise, and Elvis’ “Jailhouse Rock,” to close out the set. The crowd cheered for more and Bobby and Steve complied, returning to play an extended Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” sandwiched with The Temptations’ “Shakey Ground,” in the middle. The night ended with the audience clapping and singing: “Love’s real, not fade away.”

Their love for Bobby is authentic.

No Comments comments associated with this post