For Jorma at 70: Hot Tuna at 40

In honor of Jorma Kaukonen’s 75th birthday, we revisit this feature from our Jan 2009 issue…

photo by Jay Blakesberg

Jack Casady remembers a prediction that Jorma Kaukonen’s first wife once jokingly made. The two musicians were so inseparable, she said, that like the blues duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, they would probably be making music together for 40 years before it was all over.

She was wrong: In 2008, Kaukonen and Casady celebrated the 50th anniversary of their first collaborations.

Although there have been stretches along the way when they haven’t played together, the bond that Kaukonen and Casady have shared—one that has taken them from high school in Washington D.C. to Jefferson Airplane and on to four decades as Hot Tuna—is undeniably one of rock’s longest and strongest.

1958

“I was 14 years old in 1958 and in junior high,” recalls Jack Casady. “My older brother, Charles, was a year older than Jorma. I met Jorma through Charles; they would come back to our house, which was a block and a half away from school, and listen to blues records, bluegrass records, jazz, rock and roll, rockabilly.”

Jack had been playing the guitar for two years and Jorma, too, had taken up the instrument. “But we weren’t ‘guitar players,’” says Casady. “We were kids at school. We were children of adults.”

“I had met Chick [Charles’ nickname] in 56,” says Kaukonen, “and in the beginning his younger brother was just a kid brother. I didn’t play music yet at that time. Later on, when I started to play music, and Jack was getting a little older too, we found out that we had music in common and we started to hang out more than Chick and I did. I was just playing by strumming songs ’cause all I really wanted to do was sing.”

“Most of our social situation revolved around cars, girls and beer, just like any other high school,” says Casady. “Then I started playing guitar and Jorma was playing guitar, plus he could sing. So I’d plug into my little 8-watt amplifier and he’d play acoustic guitar. We’d do Buddy Holly and Gene Vincent stuff. At that time I had a Fender Telecaster that I bought for $115 with newspaper route money.”

“Jack was certainly more technically into the music than I was,” Kaukonen says. “He was playing pieces from sheet music, which I certainly was not doing.”

Eventually, the two boys played a handful of gigs as members of a band called The Triumphs.

“I liked Triumph motorcycles, and it looked cool on the drum head, so we were The Triumphs,” says Jorma. “I think our first paying gig was at a high school sorority party and we made five bucks. We went out to the hop shop afterward, which was like a McDonald’s kind of thing.”

“Neither of our parents ever expected us to make music our single profession,” says Casady. “But it was very exciting. It was a whole other world. It was leaving the kid world of high school and going into the adult world.”

1968

With hit singles such as “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit,” era-defining albums like Surrealistic Pillow and Crown of Creation, and a must-see live act, Jefferson Airplane had quickly ascended to rock royalty status. Kaukonen had been a founding member in the spring of 1965; at Jorma’s invitation, Casady joined before the year was out. When he first stepped off the plane from D.C., Kaukonen had never heard him play the bass guitar.

By 1968, Jefferson Airplane had become one of the world’s most innovative and popular bands, the highest-profile representation of the exploding San Francisco scene.

“When I listen to that stuff,” says Kaukonen about the Airplane’s music, “some of it is so idiosyncratic that it just doesn’t groove to me today. But I find it interesting, and without that cast of characters I couldn’t have made that music. I don’t think any of us could have. And I find that sort of exciting in a way. It’s really a crystal of what art is: Things come together in that moment and all of a sudden there is something. All of the people that were involved in that band were talented people. Would [any of us] be the same if we had not played together? The answer is obviously not.”

“To me, you go on a creative wave,” says Casady. “It has a beginning, a middle and an end. You peak at some point and then you kinda regroup and think about things and then it hopefully goes back up again. We had driven that kind of sound up to that point. Then it tapered off and band members started to concentrate on their own stuff and we started to split apart as a band. But I think as a band we really achieved something, and we achieved it rapidly through the years leading up to that.”

Jorma and Jack both recognize the contribution that the other made to the Airplane’s sound. Says Casady, “Jorma had the ability to take material that came from so many different backgrounds and weave these piercing, sharp, melodic, single-line notes throughout it, while I was churning away on the bass trying to move this stuff and get it to be more accessible and have some swing to it.”

“When I listen to the music today I think the sound was really predicated on [drummer] Spencer [Dryden] and Jack,” says Kaukonen. “The rhythm section drives a band. You have the writers, you have the chords, but once you get the elements of a band together, the sound, in my opinion, is dictated by the rhythm section.”

“[When Jefferson Airplane started out] Jorma and I realized we had to do something in order to not make it sound like a folk band,” says Casady. “Jorma hadn’t played electric guitar a lot and he hadn’t played it in the function that he’d be using it for Jefferson Airplane. I took what I’d done on the bass guitar, which was coming more out of a rhythm and blues background, and moved some of the jazz sensibilities that I had been listening to and been more aware of into a more aggressive rock format.”

“Because Jack and I played together so much, my lead style evolved in a parallel way with [his bass playing],” says Kaukonen. “I certainly wouldn’t have gotten to where I am today had he and I not spent so many hours playing together.”

A huge number of those many hours were spent outside of the context of Jefferson Airplane. Jack and Jorma began exploring their mutual love of blues forms, out of which the still-ongoing entity called Hot Tuna would be born.

“Jorma and I used to carry our guitars everywhere,” says Casady. “And at the drop of a hat we’d go into clubs after we’d do a show and go up on stage and play something. Jefferson Airplane didn’t serve all our purposes. We were really more involved in the exploration of music and what new things you could find out. So that’s why we found ourselves making extra time. And of course, being young, you could stay up for 24 hours.”

Jefferson Airplane in 1970 (l-r) Grace Slick, Paul Kantner, Joey Covington, Jack Casady, Marty Balin and Jorma Kaukonen

1978

After the various factions of Jefferson Airplane wandered off in opposite directions in late 1972—there never was an official breakup—Kaukonen and Casady became Hot Tuna full-time. The acoustic blues of their self-titled, live debut album, released in 1970, gave way to an increasingly more ear-splitting electric blues-rock. But by 1978 Hot Tuna, like the Airplane before them, had drifted apart. Although Kaukonen and Casady would reunite five years later and carry on where they’d left off, the end of the 1970s was a period of reevaluation and new avenues for both. For Casady, that meant a surprising (to fans) detour into the new wave music of SVT, a band that eschewed the long jams of Tuna for shorter, more pop-oriented songs. Jorma, meanwhile, launched his solo career.

“We just sort of stopped playing together,” says Kaukonen about his temporary professional separation from Casady. As with the Airplane, there was never an agreement to go their separate ways, not even a discussion. It just happened.

“My ex-wife, may she rest in peace, was very ill with a hyperactive thyroid and I was spending 24 hours with her,” says Kaukonen. “If I was capable of being a little more of an adult I would have dealt with this in an adult way. But what I did was spend every moment with her and that meant I couldn’t do Hot Tuna.”

Although they didn’t speak regularly during the extended Tuna sabbatical, Jorma and Jack did stay in touch, and occasionally checked out each other’s new ventures. “Jorma came to my debut show with SVT at Bimbo’s 365 [in San Francisco],” says Casady, “and I saw him do solo shows. It wasn’t an uncomfortable period for me, but at the same time you realize that things happen. I think the good thing that came out of [the hiatus] is that we’re playing better together today than ever, and it’s a healthier relationship in the last 20 years, since we’ve both been clean and sober. The drugs and alcohol back then certainly played a part in dampening our communication skills.

“Don’t forget, we were still young men,” he adds. “In a certain way you make mistakes and in a certain way mistakes are never mistakes because you always learn from them. So for me it was good to get into a band where I really tried to distill my playing down to within a slightly different style. It was a great learning experience and it was a band that was very near and dear to my heart. I had a lot of fun, but that only lasted about three years. It was a period of a certain amount of uncertainty. It’s hard to put your finger on it but I think it was a period of time for me personally where my reactions became more important in my life than my actions.”

Looking back on the formative Hot Tuna years, Jack and Jorma have mixed feelings about the music they produced, especially during the latter half of the 70s as it became blisteringly loud and aggressive.

“From my point of view, it just happened and it seemed logical to do it in that way,” says Kaukonen. “I followed a lot of interesting paths and a lot of stuff developed out of it. I certainly wouldn’t be interested in playing in a power trio today but when I listen back to that stuff, in some respects it sounds like somebody else but, as when I listen to the Airplane stuff, it’s, ‘Wow, we were pretty good!’”

“I listen back today on some periods less comfortably than others,” agrees Casady. “[Fans will say to me about a given song], ‘You played it like this.’ And I’ll say, ‘Well, yeah, I played it like that in 1974.’ When we approach a song today it might be the same song but we’re approaching it as who we are today.”

“I was basically trying to keep my life together as best I could [then],” says Kaukonen. “I did a lot of things under pressure that I probably wouldn’t do today. But out of that came some interesting stuff. Whether it’s interesting good or just interesting I’m not sure. I wouldn’t write a song today called ‘To Hate Is to Stay Young.’ But you know something? That’s where I was then. I really am a pretty honest songwriter and that’s where I was.”

1988

“The 80s and part of the 90s were dark years for me for a lot of reasons,” admits Kaukonen. “And without climbing on the God bandwagon, I will say that I truly believe someone—he, she, it—had other plans for me. Otherwise I could be dead like a lot of guys I knew. My life hadn’t really coalesced into any sort of purpose at that time but I think the beginnings of where I am today were really evident in my relationship with Vanessa.”

Vanessa Lillian became Kaukonen’s second wife in December 1988. The couple had met while Jorma was living in Key West, Florida. The following year

they purchased a plot of land in the Appalachian foothills of southeastern Ohio that, nearly a decade later, would serve as the site of Fur Peace Ranch, a guitar camp at which both Kaukonen and Casady would spend much of their time teaching.

But first there was the matter of surviving a Jefferson Airplane reunion. Hot Tuna had picked up again in 1983 but both Jorma and Jack had kept their options open. While Jorma flitted between various musical scenarios—he fronted some new bands and even played some gigs with ex-Weather Report bassist Jaco Pastorius—Casady alternated between Tuna and The KBC Band, a short-lived unit in which he was co-billed with former Jefferson Airplane cohorts Paul Kantner and Marty Balin. Jorma sat in with KBC at one gig, an olive branch was extended, and the wheels were set in motion for a Jefferson Airplane reunion album and tour that would come to fruition in 1989.

Most involved agree the reunion was a disappointment. “It was tough,” says Casady. “At that point everyone was still a child, emotionally, involved in their alcohol and drug use, and that played a part in how we picked up fights we’d started in 1972. It didn’t stay true to the traditions of what Jefferson Airplane was back in the day, which was a band coming together with all this talent. I’ve always said it was just like five ex-wives coming together onstage. It was very difficult. But the saving grace is always in live performance, and there were some good shows.”

“They promised me a lot of money and I believed them,” says Kaukonen about the reunion. “That’s probably why I did it. But that said, it pulled me back into a quasi-mainstream milieu and in a way it jump-started my awareness of the music business again.”

And for Casady, who’d been living in New York for the past few years, at least one positive thing came out of it all: While in L.A. for the initial meetings to discuss the reunion, he met Diana Quine, who would become his wife. Jack and Diana have lived in Los Angeles ever since.

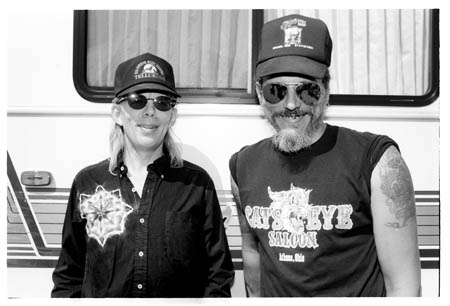

Jack and Jorma in San Francisco, 9/21/91 photo by Jay Blakesberg

1998

Jorma and Vanessa moved to Ohio in 1991 but it would take another seven years before Fur Peace was ready to open to students. In the meantime, Kaukonen and Casady continued to do what they did best, and the ’90s was marked by the longest-lived Hot Tuna lineup, with Pete Sears (ex-Jefferson Starship) on keyboards, Michael Falzarano on second guitar and Harvey Sorgen on drums. Vanessa assumed management of both Jorma’s and Jack’s careers as well as the development and operation of the camp.

“Vanessa had the vision,” says Jorma. “She’s a good businesswoman so she spearheaded the bank loan with the aid of my name and with my support she was able to make it happen. Now we’re finishing our eleventh year. There have been more blessings involved in that than I could have possibly imagined. It sounds sappy to talk about a lot of this stuff but for some reason we seem to have an effect on people. I recently got to do a show with Warren Haynes and Jack at my own theater. Just the flow of music and energy that has been an integral part of my life since it started—it’s been amazing.”

Casady concurs: “Vanessa coming into the picture and turning some of these ideas into procedural steps that got things actually done hadn’t happened in our financial world before. It’s amazing that both Jorma and I, coming from reasonably well-to-do families who certainly knew how to watch after their nickels and dimes, managed to work in such opposite directions from our own good. But with Vanessa our business started to settle down into a business of trust. She’s never taken sides and that broke down any suspicion about any of our financial feelings and we started actually building for our future—the things some adults do soon after becoming 21.

“People gave them [the Kaukonens] all the usual warnings, that three to five years is the critical time,” Jack continues. “But by being very conservative in the way they spent and not charging too much they were able to build it up. It really grew and it was doing amazing things for us as musicians too. As Jorma has pointed out, the kinds of things that we’ve learned in the last 10 years as musicians, about the craftwork of what we do, are the kinds of things that many young musicians learn now at a very early age. As you learn to teach you learn more from teaching. Jorma has always taught, no matter where he was; he was always showing people things. I taught music before I came out to California but just in the back of a music store in order to keep my $50 a month rent going. But when he said, ‘I want to build a school here, and to put it together with Vanessa’s business abilities and her ability to tap into what the school should be about,’ things began to grow.

“That weekend with Warren Haynes,” he continues, “was as much of a musical milestone as there’s ever been for me. And Warren said the same thing: ‘This weekend is what I got into music for.’”

Having the opportunity to make music in the informal setting of Fur Peace Ranch with a steady stream of guest instructors and performers has also served to broaden Jack and Jorma’s musical horizons. “It makes things more interesting for both of us,” says Kaukonen. “There’s always something new coming up. We’re always figuring out different stuff. I think it’s a really good thing for both of us. It certainly is for me. I actually kind of know what I’m doing now.”

2008

Life is good for Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady. At 68 and 64, respectively, they are still actively making music together—and still enjoying one another’s company.

Hot Tuna itself will turn 40 in 2009 and is still evolving musically. For the past few years, Jorma and Jack have worked with mandolinist Barry Mitterhoff and, in a partial return to the electric music they’d left behind for some time, with a new drummer, Erik Diaz. Jorma’s solo career has continued unabated as well. His 2002 album Blue Country Heart found him switching gears and exploring country music’s roots in the same way he had always delved into the blues. The album was nominated for a Grammy and was followed by 2007’s Stars in My Crown, which struck a balance between blues, country and gospel music.

Jack has continued to work with other musicians, in particular sitting in when time allows with the band Moonalice, which includes Pete Sears, guitarist G.E. Smith and others. And he even released a solo album, 2003’s Dream Factor. Jack co-wrote much of the material, and brought in friends like Warren Haynes and Little Feat guitarist Paul Barrere to help out. Much to fans’ chagrin, however, Casady did not choose the occasion to make his vocal debut.

Jorma and Jack remain the best of friends. “I have the utmost respect for him,” says Casady of his musical partner of half a century. “We’ve watched each other go through many trials by fire, both personal and professional. He’s an extremely well-learned person that has grown immensely within himself. I’ve watched this. He now has a young family. He’s got Jorma-land out there. But what’s fascinating about what he does is he really is a teacher and he gives an enormous amount of time to explaining things to people. And his patience and energy level are unbelievable.”

“We’ve been called the ‘Odd Couple of Rock and Roll’ and you can guess which one he is,” jokes Jorma. “That’s kind of what we’re like, really. We’re very different guys but for some reason we just get along really well together. I think we consciously understand each other better. And as we slide gracefully into our golden years, our friendship has deepened and become more profound. The bond that Jack and I have is that we know who we are; we know where we came from. That has contributed in a huge way to the fact that we can play and create so much together. It’s about respect.”

As for Hot Tuna’s tenacity, Kaukonen surmises that the music has thrived so long “because we’re honest in what we do. I can’t exactly put my finger on why people like what we do, but I think it has to do with honesty and the fact that we’re fun most of the time.”

“Hot Tuna,” says Jack, “exists for its own musical value. The [Airplane] stuff had a lot of political elements and a lot of young, aggressive elements, a lot of romantic elements, and a lot of elements that came together with the personalities involved. It really was a band of personalities. So I think when you understand that, you enjoy the music better.

“At the end of the day,” he adds, “we both love to pick the instrument up and play. It’s not about posturing. It’s about the emotional and intellectual aspects of playing music that got us in it in the first place. There’s no histrionics and no drama—we just really look forward to doing what we like to do.”

“And,” adds Jorma, “you still never know what’s gonna come next.”