Exhibiting the Bill Graham Revolution: Alex and David Graham on their Father’s Immense Legacy

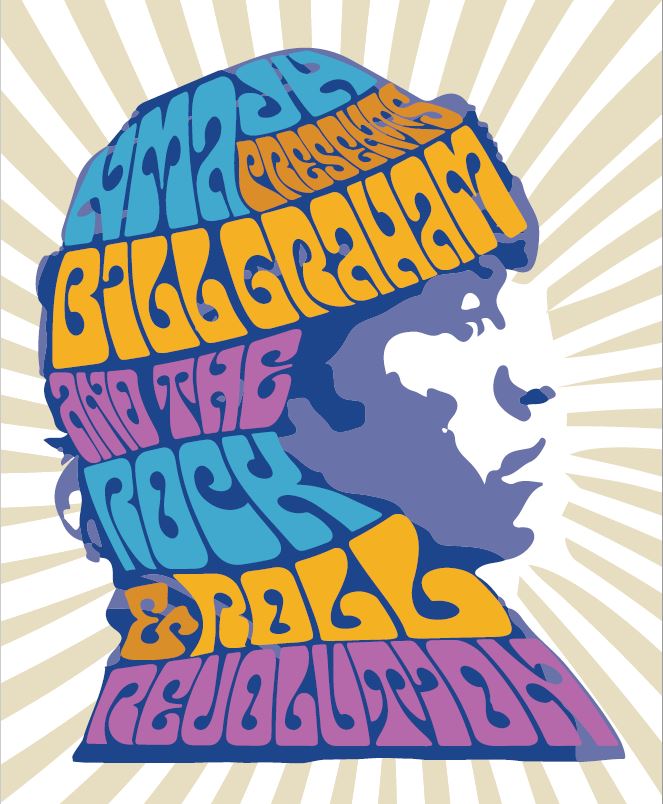

“Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution” is a true labor of love. The exhibition tracks the extraordinary life and legacy of the renowned rock impresario—from his arrival in the United States as a 10-year-old Jewish immigrant fleeing the Nazis through his work with the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the founding of his Fillmore venues, his charitable endeavors and his close relationships with artists such as the Grateful Dead,The Rolling Stones, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana and The Who. The show incorporates concert posters and rock memorabilia, along with photos, films and other archival items that assist in telling the captivating story of the fabled concert promoter. While the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles originally organized the exhibit—in January, it will complete a run at Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History. The impetus came from Graham’s two sons, David and Alex, who had been thinking about the proper way to memorialize their father, who passed away at age 60 in 1991 in a helicopter crash.

“Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution” is a true labor of love. The exhibition tracks the extraordinary life and legacy of the renowned rock impresario—from his arrival in the United States as a 10-year-old Jewish immigrant fleeing the Nazis through his work with the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the founding of his Fillmore venues, his charitable endeavors and his close relationships with artists such as the Grateful Dead,The Rolling Stones, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana and The Who. The show incorporates concert posters and rock memorabilia, along with photos, films and other archival items that assist in telling the captivating story of the fabled concert promoter. While the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles originally organized the exhibit—in January, it will complete a run at Philadelphia’s National Museum of American Jewish History. The impetus came from Graham’s two sons, David and Alex, who had been thinking about the proper way to memorialize their father, who passed away at age 60 in 1991 in a helicopter crash.

What are the origins of the exhibition?

ALEX GRAHAM: My brother and I have been working on this project for about four or five years. After our dad died, his office in an Francisco was like a museum, in the sense that it reflected the 2-year history of Bill Graham Presents. He also had his own archive that he kept at his home in Mill Valley, but there was a lot of stuff a the company. So, although the company changed hands over the years, my brother and I had a long-standing agreement with the company that everything on the walls of the office could remain there unless they were to vacate the building, which is what happened at the end of 2008.

So I went out there and spent several days basically working with my dad’s archivist, James Olness, and we packed up a museum’s worth of archival items such as photos, memorabilia and posters. I set up a warehouse in San Francisco and started flying out there regularly for the next couple of years, building a database and restoring a lot of things. Having James help me was invaluable because he’s sort of an encyclopedia of what everything is, where it came from, who the photographer was, etc.

James, my brother David and I eventually decided that we didn’t want to just keep it to ourselves. Dad never viewed these materials as a commodity; it’s not something he ever thought to sell. So, along with some other people in the foundation, which we set up after Dad’s death—the Bill Graham Foundation—we came up with the idea to put together a small sort of retrospective on his life.

There was someone on the board who had a relationship with a place called the Lush Life Gallery. It’s this gallery that’s only about 1,000 feet, but it’s right around the corner from the Fillmore and it’s also a part of the Jazz Heritage Center. So, along with my brother, James and some of the people in the foundation, we took all these items, along with some other things that David and I had at our homes, and created a story about our dad’s life called “Presenting Bill Graham.”

We had this really cool idea to use Bob Greenfield’s book [Graham’s autobiography, co-written with Greenfield Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out], so that the captioning, whenever possible, would be in the first person. So if you were looking at a picture of Dad up in the Catskills, working as a waiter shortly after the Korean War, there would be a passage in the book where he might talk about an experience, such as running dice games late at night, after dinner had been served, which made it so much more intimate.

It was very successful in terms of the emotional connection we wanted it to have, and a lot of people came out of the woodwork to see it. One of those people was a guy named Bob Kirschner, who is the director of the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. He said, “This is a phenomenal show. I assume that you have a lot more content than you were able to put on the walls?” We told him: “Yes, of course.” And he basically said, “I’d love to talk to you about bringing it to Los Angeles and creating a full-blown museum exhibition.” We just thought that sounded great.

How is your father’s life organized and presented?

ALEX: It’s a timeline; it’s constructed in a linear way. It begins in 1931 when Dad was born in Berlin as a Russian Jew. A few years later when it was really not a good time to be a Jewish kid in Berlin, he fled, and the exhibition sort of goes from there, tracking his path across Europe and how he got to America, and then everything that he did here after.

What’s been fascinating is how some people who knew Dad most of their lives learned a few new things—I’ve learned a lot of things myself just from doing the research behind what went into this show. I’d say the most moving experience I had while working on this was meeting a guy named Ralph Moratz, who sadly just passed away within the last year. He was a companion of my dad’s when they were young boys, walking across Europe by foot escaping the Nazis, roughly between 1939 and 1941. They were both orphans and they both wound up in New York together and, eventually, lost touch. I had never met anyone who was with my dad at that stage in his life, not even close. I think the earliest first-person stories somebody told me were probably from the Catskill years. So Ralph is in the show and there are some video testimonials of him talking about their journey. That’s probably my favorite part of this show.

I think a lot of people will go primarily for rock-and-roll—most people probably don’t even know who Bill Graham is unless they are fans of rock history. But I keep hearing not only that the numbers are off the charts, but also that the demographic diversity is unlike anything people have ever seen. I think that’s indicative of the fact that a lot of people are coming for one thing, but what is resonating with them is much broader than what they may have originally intended. For example, a lot of people come and they just want to see poster art, or they come for the photography, or because they just love The Doors, but then they end up being confronted with this story that covers the first 30 years of his life—even before he got into the rock-and-roll business, which is pretty intriguing, quite frankly. I think that it is such a profound thing for someone to go through what he did and then go on and basically create an entire industry.

Speaking of that journey, one of the items in the exhibit is an early 1950s Bronx phone book. Can you talk about its significance?

ALEX: It’s a fascinating part of his story and it’s emblematic of the fact that you could not come up with a more self-made man in every sense of the word. He came here with nothing, he was 10 years old—he weighed 40 pounds, he had rickets. He had nothing but the shirt on his back and a prayer book and a yarmulke. He had no idea what happened to his family.

So, after spending nine weeks in an orphanage upstate, he was adopted by Alfred and Pearl Ehrenreich in the South Bronx. He grew up on Montgomery Ave. He barely spoke any English—actually, he did not speak any English. He spoke German and a bit of French, and he had a German accent because he was German. The kids in school used to kick his ass and call him a Nazi, and obviously the irony of that is off the charts. So he was desperate to assimilate into American life and culture, and forge a new identity for himself. He used to go to the movies all the time. Bob Greenfield told me that my dad used to go to John Garfield s movies and mimic his lines, and that’s one of the things that helped him drop his accent.

So, in furtherance of this forging of a new identity for himself, he took his birth name, Wolfgang Grajonica, which is WG, and he opened up a Bronx phone book and decided he was going to change his name to William Graham. And that’s where Bill Graham comes from; he literally picked it out of a Bronx phone book.

Can you reflect on your father’s legacy as a concert promoter?

DAVID GRAHAM: I think he followed the basic idea of “Treat people the way you would want to be treated.” He took the attitude that the venue was his home and the fans were his guests. His famous analogy was to look at the show as the meal: He’s presenting the main act and that’s your meat, the opening act is your potatoes and you’re inviting people in to eat this meal—and what my dad did was put the parsley on the plate. You don’t need it, but that meal seems a lot better with that parsley on the plate. And that parsley is good sound, good lights and being treated with respect; it’s the barrel of apples in the hallway at the Fillmore and being open to presenting all kinds of artistic expression. It’s amazing shows like Miles Davis opening for the Grateful Dead and treating people with respect.

He was also very lucky at the time to stretch his wings as a promoter. Nowadays, when a band tours, they call the shots—there’s no local promoter telling them what to do anywhere. It’s a different era, and what’s lost today in concerts is the personality—the connection between the local promoter and the fans was a big deal. The promoter knows how to treat his fans a certain way and that sort of art isn’t around anymore; it’s much more corporate, and that’s too bad because what made concerts special is that special attention.

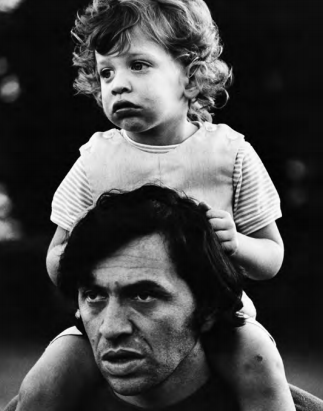

DAVID: I don’t know where [that photo is] from, but it’s around the time Dad was closing the Fillmore. What it reminds me of is the movie of the Fillmore closing [Last Days of the Fillmore]. There’s a lot of clips of my dad and I hanging out in the park and he’s talking about why he’s retiring, and he’s alluding to the fact that he has a young family and I’m running around. For me, it’s emotional and evocative because I’m really young and here’s my dad being young and robust, talking about wanting to live his life with his family.

DAVID: I don’t know where [that photo is] from, but it’s around the time Dad was closing the Fillmore. What it reminds me of is the movie of the Fillmore closing [Last Days of the Fillmore]. There’s a lot of clips of my dad and I hanging out in the park and he’s talking about why he’s retiring, and he’s alluding to the fact that he has a young family and I’m running around. For me, it’s emotional and evocative because I’m really young and here’s my dad being young and robust, talking about wanting to live his life with his family.

It reminds me of that time period when he found so much great success. He had a really unique life. He went from not even knowing what rock-and-roll was to being the godfather of the scene only three or four years later. That picture of me on his shoulders just represents that time period and how much great stuff was going on and, personally, how much difficulty was also going on—it wasn’t all bread and roses.

DAVID: First of all, [Bob] Dylan is a very nice guy, and I almost feel sorry for him because he’s been an iconic figure for 50 years now. But he was a nice man and he had a real affection for my dad. e asked Dad to do his tour in ‘74 with The Band, and there’s a great story about how Dylan only wanted to do 12 shows, but when my dad was done with him they had like 45 shows scheduled. That was a big deal because back in the ‘70s, these big national tours were new. He also did Dylan’s ‘84 tour through Europe. They had a really good relationship.

I was very young when these things happened, so there was no suspicion of me. I was just a kid, so someone like Bob would be very friendly because I wasn’t trying to get anything from him, and I could tell that he liked my dad a lot.

DAVID: My dad was the tour director on the ‘81 Stones tour—that frankly rejuvenated their career, if you really analyze it—and on that tour, Keith had a pair of boots that he was in love with. He would never play without these boots and, in San Francisco, at a show at Candlestick Park, his heel broke off on one of the shoes. Emblematic of how hands-on my dad was, he grabbed these boots and he personally took it upon himself to fix them, and my dad was the furthest from a fix-it guy or a carpenter. So here’s my dad tracking down a hammer and a nail and hammering the heel back into this boot and giving it back to him so he can play.

At the end of the tour, Keith gave him the shoes back as a gesture of love. That’s the type of stuff my dad would do. I think there’s a scene in the Fillmore movie where he’s trying to fix Jerry’s guitar when it broke. My dad was the least technical person you could find, but that’s the kind of person he was; he was so on top of everything and took each thing very personally. He also wanted to take personal care of the people he hired and the people he invited into his concerts.

ALEX: When Reagan visited Bitburg, which was a cemetery in Germany where SS soldiers were buried [but the president did not visit any Nazi concentration camps], Dad was very upset. He staged a rally in San Francisco in Union Square, and he took out full-page ads in multiple newspapers across the country in protest. And then someone threw Molotov cocktails into his office an they basically burned it to the ground. They never found out who did it, but the timing and the connection doesn’t seem too far-fetched. Many of the contents of the office, including a lot of the archival items—some of which are in the show—were fire damaged. The menorah was in his office and it partially survived. That was actually the most difficult thing, logistically, to transport.

It’s really intense. There’s a plaque at the base of it that says “Survival” and my dad was seemingly indestructible. I never saw him afraid of anybody. I never saw him back down from anybody. I never saw him give up at anything. The more someone or something challenged him, the harder he would proceed in doing whatever needed to be done to get it done.

The menorah reflects his religious identity and how, culturally, he was a Jew, but it also demonstrates that theme of survival and reinventing himself, and the triumph he went on to create.

DAVID: Carlos [Santana] lent us a couple guitars, including one of his ornate ones from his festival period in the ‘70s. We’re still pretty close with Carlos, and he was very nice and lent us something really pretty. I mean, that could be in a museum. That’s another thing that’s clear in the show—Dad had a very close relationship with everybody, and that comes through. There’s a lot of love in the show, and I don’t mean that flippantly.

DAVID: Carlos [Santana] lent us a couple guitars, including one of his ornate ones from his festival period in the ‘70s. We’re still pretty close with Carlos, and he was very nice and lent us something really pretty. I mean, that could be in a museum. That’s another thing that’s clear in the show—Dad had a very close relationship with everybody, and that comes through. There’s a lot of love in the show, and I don’t mean that flippantly.

DAVID: New Year’s Eve was always the best moment of the year. It was his shining moment and crowning achievement. Every year, he played Father Time, and he would bring the New Year in with some kind of themed theatrical production. As you see, one year, he came in on a mushroom; one year, he came as an eagle and hatched the babies coming out of the eggs; another year, there was a huge bridge that went across the floor. There was always a really fun interplay between him and the Dead, who had heard what he was going to do but were very protective of their own space.

Dad always had huge bags of balloons that came down at midnight, and Dad pissed them off by putting the balloons right over the stage. They always requested that he didn’t, and he would always put two big sacks right above the stage. It was always the highest moment of the year, and I mean that both ways. It was always the most joyous of the year; everybody was on the same wavelength.

Of all the great shows I’ve been to with Dad, the closing of the Winterland has always been my favorite concert experience, and I was only 10 years old. It was such an epic and emotional thing. It was a five day run. All the Deadheads were lined up for New Year’s Eve after the show on the 30th, so there was a line around the Winterland overnight the night before New Year’s [Eve], and we served carrot cake and soup on the corner at like 5 a.m. Then, the Deadheads were let in during the early afternoon to watch Animal House, and then The Blues Brothers played, so John Belushi was onstage in front of you. Finally, the Dead played all night and we served breakfast in the morning. Probably my favorite part of the whole evening was that they pre-rolled about 5,000-10,000 joints and gave them out to the audience as part of the experience, and told the cops they were doing it beforehand. That’s the stuff that just doesn’t happen anymore.