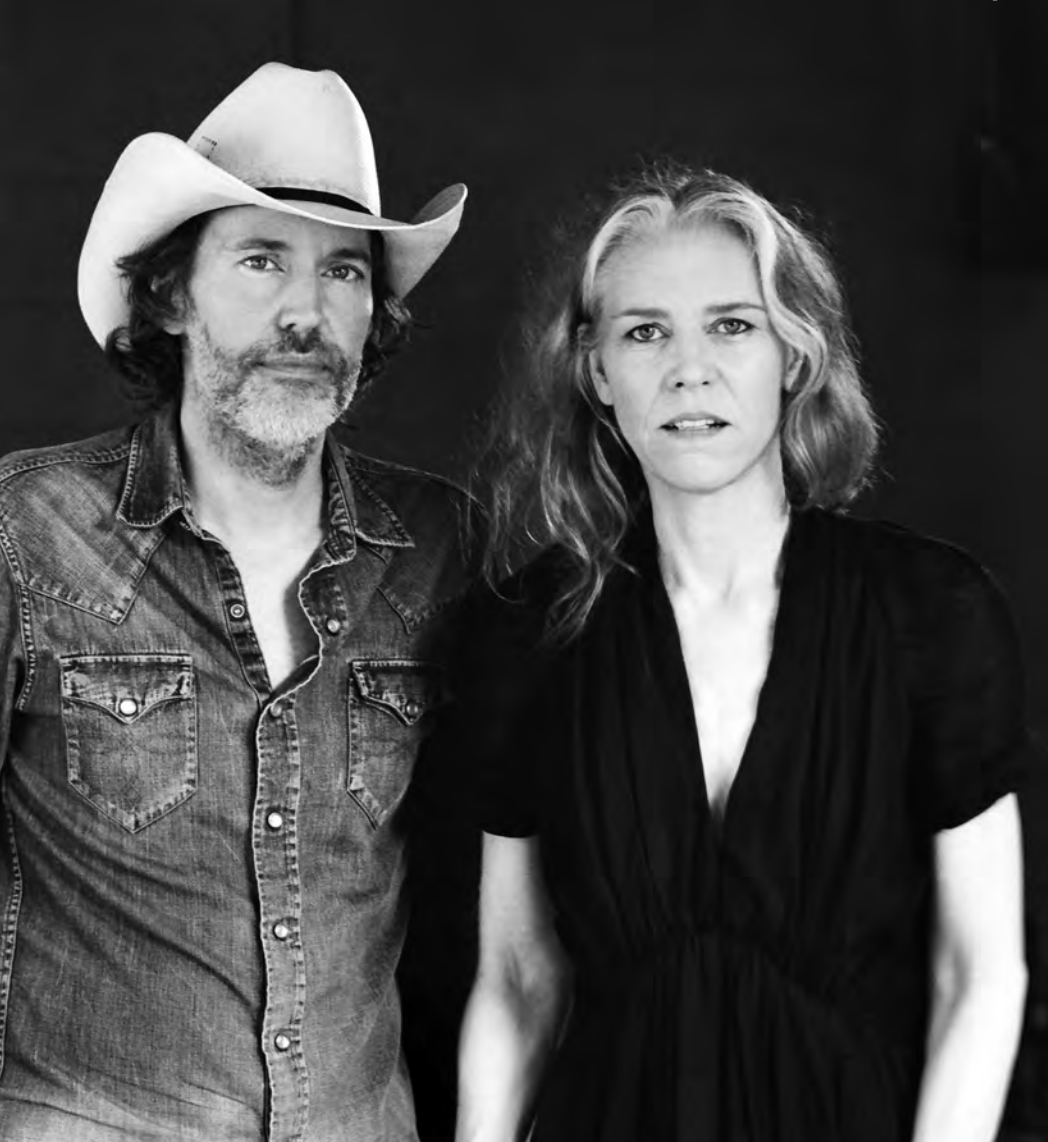

Interview: Gillian Welch

“We’d been thinking about this for some time,” Gillian Welch reveals as she reflects on her new archival release, Boots No. 1: The Official Revival Bootleg. Welch and musical partner David Rawlings combed through an extensive collection of recordings associated with their debut album, 1996’s Revival (including demos, live performances and alternative studio takes), in order to select the material that appears on the new two-disc set.

“We’d been thinking about this for some time,” Gillian Welch reveals as she reflects on her new archival release, Boots No. 1: The Official Revival Bootleg. Welch and musical partner David Rawlings combed through an extensive collection of recordings associated with their debut album, 1996’s Revival (including demos, live performances and alternative studio takes), in order to select the material that appears on the new two-disc set.

T Bone Burnett produced the Americana milestone after witnessing a performance by Welch and Rawlings at Nashville’s Station Inn. The ensuing collaboration would not only bear fruit on Revival, but also on 2000’s landmark soundtrack to O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which was produced by Burnett with the assistance of Welch and Rawlings’ visions and voices. Boots No. 1, which includes eight previously unreleased songs, supplies a richer context for enjoying Revival and is a rewarding offering in its own right. Moreover, as its name also suggests, the release is the initial installment of a new series from Welch’s Acony label.

The release of Boots No. 1 marks two decades since Almo Sounds issued Revival. Was the anniversary the sole consideration that led you to revisit this material or was there another precipitating factor that led you to issue it as the debut of your new Boots series?

The 20-year anniversary of the record kind of pushed us to do it now. I won’t really speak for Dave, but I was almost a little embarrassed that we had all these tapes and we’d never done anything with them.

We started to go back and look at the Revival outtakes 10 years ago, just to see what we had because from the moment when we started our own record label, around the time of Revelator, we’ve been in possession of all the tapes. So, we had access to them, and we made an initial foray 10 years ago to see what there was, but then we put them back on the shelf.

And then, here comes the 20th anniversary and, as I said, it was a little bit of an embarrassment for me. We’d been taping all the live shows, and we had home-demo tapes, just tapes and tapes and tapes. We wanted to crack open the door to get ourselves thinking about how to deal with all this unreleased material that we have. So this time, we finally did it.

It was almost like a mental game for me to think about this whole other series—this whole archival arm of the label—to differentiate it from the new releases. So that’s what the Boots series is. I find it helpful and I think Dave finds it helpful. That’s how it started.

Do you already have something in mind for Boots No. 2? You mentioned live recordings, so will it be an archival performance?

We kind of know what No. 2 will be, but I don’t think it will be live. But I do think that will happen, eventually. Going through the process of curating this bootleg, we’ve already bumped into a couple of early shows of ours right around the Revival time. There are complete shows that are nice—either just preceding or right after making Revival.

I would put them out in their entirety because I think they are a nice snapshot of that moment in time. There’s some unexpected stuff. There are some shows where Dave goes over and picks up an electric during the show. It wasn’t quite so formalized as it is now. But, yeah, I think it will be an outlet for live recordings.

As you spent some time with all the music from the Revival era while preparing this release, what, if anything, did it reveal to you?

We’d barely done any studio recording prior to the Revival sessions. There were just a handful of demos, but nothing like a record session where you’re in there for weeks. I thought it was interesting how both Dave and I heard our singing change. I learned to sing—or sing differently— over the course of the session because it’s probably the most singing I had ever done. Playing a show a night—that’s a lot of singing. But being in the studio for 8-10 hours a day, every day for weeks—that is a different thing. I became much more of the singer I am now during those sessions, and I was surprised to find that I could hear it happen. A lot of people have commented on the singing, although they don’t know, necessarily, that that’s what they’re hearing.

Can you talk a little bit about the discovery and evolution of your vocal blend?

Dave and I had sung together in country bands and bluegrass bands in Boston. Then, in the summer of ‘92, we both moved down to Nashville and away from our other musical pals. That was the first time we ever sang and played with just the two of us. So we started doing the same thing we would do in Boston—we started playing bluegrass classics. We sat down in his kitchen and the first song we played was “Long Black Veil.” Then, we played “Rank Stranger” and, when we stopped and compared notes, we both said, “Wow, we’ve got a pretty good natural blend.” We agreed that our voices basically had something good together.

Of course, over the years, that has become more so. Now we have identical vocabulary. We’ve been singing together so long that all of our inclinations are completely in sync. So it’s even better now, but back then we did have some natural affinity.

I credit Dave with then saying, “OK, we need to play now as much as we can.” At the time, the only thing available to us in town were these writers’ nights at a bar or a hotel lounge—they’d have these writers’ nights where you would go in, and you put your name on a list and waited. You’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait and then, eventually, they called your name and you got up, you played two songs, and then you went home. We started doing this as much as we could stomach: three, four nights a week. There were lots of writers’ nights in town of varying levels of reputability. If they went well then, eventually, you’d get booked for a 20-minute slot somewhere and work your way up the food chain.

Then we got a three-hour gig on a weeknight at a bar down by Elliston Place from 7 to 10 p.m., and I just remember that because I had only written three songs, so we’d play one original per hour. [Laughs.] All the rest were covers: Stanley Brothers and Woody Guthrie and The Carter Family, and all the singer-songwriters that I was influenced y like Robert Earl Keen, Nanci Griffith, an I guess there would be a Bob Dylan song in there because we used to do “Oxford Town” in that set. And all that was important for getting our sound together. Every show we ever played working up to Revival was a duet show. Our band was a duet.

So, when you would perform with Dave in those groups up in Boston, the two of you would never just sit together and play as a duo?

No, we never did. There were always other musicians around.

Thinking back to your time at Berklee [College of Music, which she attended with Rawlings], what did you take away from that experience?

In some weird way because I seemed to like this kind of music that not too many people were into up there, it bolstered and strengthened my aesthetic and opinions. Most people had no idea what I was talking about if I said The Stanley Brothers. There was no discussing it. So I just didn’t have any conversations about the stuff I really liked. And I think that ended up being really valuable for both Dave and myself because we just had our opinions and it didn’t matter. [Laughs.]

But in a way, that was born out of the school environment, where it didn’t matter that the other people were practicing Yngwie [Malmsteen] licks. It didn’t matter. What was I going to do? Was I going to talk to them about what’s incredibly ecstatic and transportive about The Stanley Brothers’ singing? No, I was just going to listen to it, and know it in my heart, and then try to do that.

It made us strong, so that when we got to Nashville, where people did know about The Stanley Brothers and, of course, they knew about Bill Monroe, we already had our heads straight. So that when it came to all that subtle stuff, the more insidious stuff, where they try to move you away from what you like, it was still the same answer: “No, this is what I like.”

Were you aware that T Bone Burnett was in the audience the first time he came to watch you perform?

No, but as soon as he introduced himself, I knew who he was. It’s funny how I knew him, though. It wasn’t his most famous work. Well, I don’t want to make Peter Case feel bad by saying that, but it probably wasn’t the record that most people would have associated him with because I think he’d already done the pretty big Los Lobos record [How Will the Wolf Survive?], and some Elvis Costello stuff King of America, Spike]. But as soon as he shook my hand and introduced himself, I said, “Oh, you made that first Peter Case record,” which was a very big record for me in the ‘80s.

That was Peter Case’s first solo record after The Plimsouls. In the ‘80s, with all its ‘80s-ness, that record was like the little signpost for “Hey, look over here, there’s this other stuff.” There were bands like that in the late ‘80s who just started veering off t ward folk or acoustic or something. They might have fringe on their shirts or they might wear cowboy boots, or they might sing a George Jones song in their encore. [Laughs.] There was not a scene, there was just all this other stuff—that’s how it was then.

Of course, there were also other people like Norman Blake. There has always been the alternate universe, where Norman would just let the world go by around him, and he would be there doing his thing. We’re kindred spirits with Norman Blake. We’d go down there and pick until our asses hurt and we had to stand up. We’re a little of the same cloth.

Boots No. 1 opens with “Orphan Girl,” and there are two versions of the song on the release. By the time you recorded that tune, there were already two well-known interpretations of it out there in the world [by Emmylou Harris and Tim and Mollie O’Brien]. Did that get in your head or influence you in any way as you were trying to record your version?

Recording “Orphan Girl” was hard. It had a couple of things that made it difficult. That as the oldest song coming into the record. It was one of the first songs I wrote when I moved to Nashville. So I had been singing it for the longest time, but I was a bit distant from the inspiration of writing it. It was already known out in the world with a couple stellar versions— Tim and Mollie’s version of it and Emmylou Harris’ version of it.

And also, for at least a couple of years, I’d had every writer in every writers’ night that we’d done just basically tell me, “Wow, that was an incredible song. That’s your best song.” So I wanted to do it justice. I started to get kind of anxious like, “Wow, I have to record the ultimate version of this song.” It made it difficult.

We tried it many, many times. That’s what you hear on the bootleg—one version where we were just trying to move it around, make it fresh again and get an honest performance of it. The track that opens the collection, the trio version of it with me and Dave and T Bone, that’s what that was—we were just trying something different to try to get a good reading out of me. And then the other version of “Orphan Girl” is the home demo, when the song’s about a week old. So it’s the opposite end of the spectrum. It’s like, “Hey, I just wrote this.”

Unlike “Orphan Girl,” which was well known by the time you entered the studio, the new record also includes “Georgia Road,” which you’ve only performed once. Can you talk about that song?

It was a song that was written just before the sessions. T Bone had heard us play live at the Station Inn and, prior to our first session with him, he had asked me for a cassette tape of all my songs. So I got together all the home demos, and Dave and I probably demoed a couple of other things that needed recording, which is what the version of “Acony Bell” [on Boots No. 1] would be, a demo just prior to the session where T Bone wanted to hear the songs.

So I sent this tape of about 30 or 35 songs to T Bone, and then we talked about them, and he made his plans for what other musicians we should get after listening to all the stuff. But I guess we finished “Georgia Road” after that tape got sent. I’m pretty sure we wrote it in Nashville because we wrote every song in Nashville. So T Bone had never heard it, and about three-quarters of the way through the LA sessions, Dave and I had a gig. We had booked a gig at McCabe’s—I guess we figu ed there’d be time, and there was. So, at this gig, we played “Georgia Road.” T Bone was there and afterwards he was like, “That’s not on the tape. What is that?” So the next day, when we went into the studio, he asked us to play that song. We only played it once because tonally it was a little outside of what we were doing. We were skewing a little more Appalachian than that.

“Red Clay Halo,” which appears on Boots No. 1, certainly seems like it would have fit on Revival. It surfaced later on Time (The Revelator), but what do you remember about the initial decision not to include it?

We thought—and the “we” is we three, the creative brain trust putting Revival together, which was me, Dave and T Bone—we all thought that it wasn’t quite as strong, sonically. The performance and our arrangement—maybe it wasn’t quite as meaningful to us in the duet, and we definitely didn’t want to enhance it with a full bluegrass band. And so, if it was just going to be a duet, there were other duet tracks we liked better.

He already knew that Revival wouldn’t be all duets— although, if you talk to T Bone now, he feels differently about it. I just talked to him the other day about this and he said, “I wish we could have made that whole record just as the duet.” But we couldn’t. I’m not sure that the record label would have been OK with that. They were nervous about the number of duets we had on there. They told me so. I got nervous phone calls—“We’re nervous that people are going to hear these duets and they’re just going to turn it off!” I was like, “Well, I don’t know what to tell you. That’s kind of what we do.” [Laughs.]

So we knew we had to find a balance of band tracks and duet tracks. That’s why “Red Clay Halo” went on the chopping block—because it was a duet track and we were full up. So it got put away for later. But we played it live all those years before we eventually recorded it.