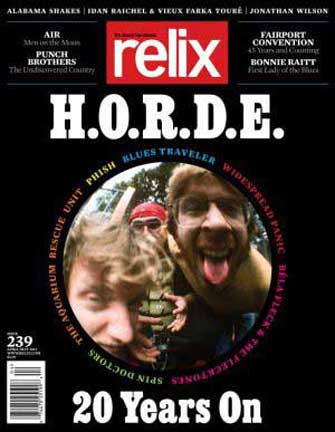

H.O.R.D.E. Core (25 Years Later)

Following Bruce Hampton’s tragic passing last night we share this story which ran in 2012 marking the 20th anniversary of the initial H.O.R.D.E. tour. Hampton and Aquarium Rescue Unit were essential to the origins and spirit of the event.

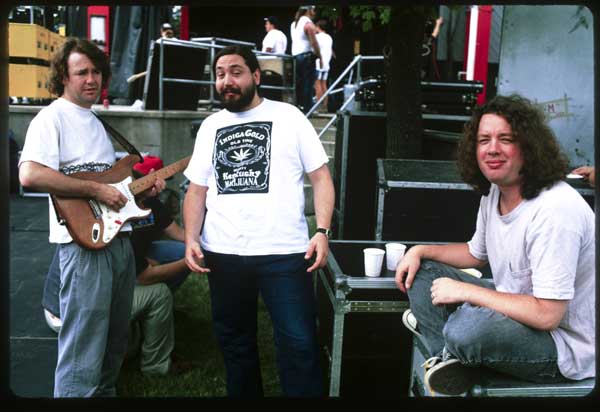

Photos by Steve Eichner

****

I’ll never forget what I heard on that walk to the venue.

It was the late afternoon of July 9, 1992 and I had just arrived at the Cumberland County Civic Center in Portland, Maine for the debut of an eight show multi-band bill that pledged to showcase the Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere. Blues Traveler manager and HORDE co-owner Dave Frey recalls viewing the “Stephen King-like” fog as a portent, describing the weather as “ominous” (of course he was anxious about the slow advance ticket sales for the event but would be appeased by a few thousand walk-ups). Such an adjective was the furthest from my mind, as I made my way to the facility, passing rows of parked cars, while their affable, energized occupants gathered nearby, chatting, imbibing but above all else representing, playing the music of the groups that pulled them across the Maine border (and a quick glance at the license plates made it clear that most of these vehicles had indeed originated from out-of-state). It was like the boosterism of the 1920s all over again but rather than preaching the virtues of their local townships, the focus was on music borders or perhaps the lack thereof, given the range of improvisation reflected in that quilt of sound.

As I walked inside, I discovered a welcome, wondrous site: five thousand animated folks showing their colors. Phish and Blues Traveler predominated the T-shirts iconography but Widespread Panic and Spin Doctors had their adherents as well (I’ll confess that I can’t remember seeing an Aquarium Rescue Unit shirt, even if they were the band that would predominate my thoughts over the days to come, leading me to a second helping of H.O.R.D.E. a few days later). In this era before the Internet had really take hold there was a prevailing sense of We Are Not Alone. Who knew that this many people would travel to Portland, Maine for 75 minute sets from these five groups (and twice that number would attend the shows at Garden State Arts Center and Jones Beach). Before the initial notes were sounded, there was a palpable anticipation fueled by a self-selectiveness that I would not experience with such intensity until the first Bonnaroo.

I would go on to write a book called Jam Bands and accompany it by founding a website, called Jambands.com. I firmly believe that my perception of a particular musical constellation first crystallized during the course of that evening in Portland, Maine.

John Popper, the Blues Traveler frontman and driving force behind the event, is reluctant to take credit for this. “That’s the thing I always debate: Are you doing the shaping or are you being shaped by your generation? It’s hard to tell. I think that H.O.R.D.E. was more about discovering the world around you. In a way H.O.R.D.E. brought you a glimpse of that in a shot but you’d have gotten there yourself. Or do you think you never would discovered the ARU if it wasn’t for the H.O.R.D.E.?”

Here’s hoping that I would have but let the record show that I did discover them that day in Portland, Maine, during their opening set that culminated most majestically with a full-band segue into Widespread Panic. There was something happening here and H.O.R.D.E. not only manifested it but gave it new form as well.

How that all came to pass began with a meeting in the Bill Graham Management’s New York office on a Sunday night four months earlier. Widespread Panic’s John Bell, the Spin Doctors’ Eric Scheckman, Col. Bruce Hampton of ARU, John Popper and a couple of his Blues Traveler bandmates and all the members of Phish came together, with no managers or agents allowed, as they discussed a plan to join forces with the hope that these five club bands could generate a collective interest that would allow them to move into amphitheatres for a few dates…

John Popper: We all met in a room in Bill Graham’s office and there was a certain reverence. If you’ve ever been in Bill Graham’s anything there’s a rock and roll reverence: “Oh that’s Janis Joplin’s tambourine, just hanging out right there.”

John Bell: That meeting up in New York was a gas. I’d never seen that before. Everything else now is promoters, agents, managers. They cook up the scenarios or you just fit yourself into something like Jazz Fest or Bonnaroo, which is great, it’s well-organized and put together. But we’d been playing with each other for the past couple years opening for each other in different territories and this was young band guys getting together and having their own ideas of what was going on. It wasn’t coming from the management, so it was really hip.

Mike Gordon: I remember managers weren’t allowed in the meeting although there were a couple hovering outside.

John Popper: Fishman wanted to stage a little skit. He said, “I’m going to run out screaming and you guys drag me back into the room so that everybody will be like, ‘What the hell are they doing in there?’ Well he got really into it with his “No, no, don’t take me back,” and he ripped the door off the hinge.

Bruce Hampton: I remember everybody was real idealistic and we all wanted to do the festival for a ten buck ticket which was unheard of.

John Popper: Then Trey [Anastasio] stands up and goes, “Why don’t we finally just make it something where it’s five different bands, equal billing, equal money everywhere no matter what the audience says.” And we’re all like, “Yes, let’s do this!”

John Bell: Then Mike Gordon brought out a jar of Vaseline and we all shook hands after ceremoniously dipping our hands in the Vaseline.

John Popper: I still have that jar of Vaseline.

Eric Schenkman: The other thing that came out of that meeting was the idea of the H.O.R.D.E. sword. Popper had someone make a sword, like a Merlin double-edged, huge knight sword and every band got one.

Left to themselves during that Sunday night meeting, the musicians devised an idealistic, egalitarian solution but then Monday morning arrived and with it came the realities of the music industry.

John Popper: The next day Trey called me and goes, “I talked to my manager and we just can’t do that.” And I understand why he couldn’t. They have to eat, they have people to pay. They would have been giving up quite a bit had they done that deal of a five way spilt. You can’t expect them to do that. My next call was to John Bell and he said, “I understand but then we have to do the same thing down south.” So then suddenly everybody’s coming to their corners.

Still, while the proceeds from each show would be apportioned relative to each band’s draw in a given market, the actual set times would remain egalitarian, with each act given 75 minutes, including Aquarium Rescue Unit, which had only minimal exposure in the Northeast but had strong allies where it really counted.

Dave Frey: Everybody had this common idea that they had to help Colonel Bruce Hampton and the Aquarium Rescue Unit. That was like the secret squirrel agenda of the whole thing.

John Bell: Bruce approached music and the whole way we apply ourselves on stage and with each other musically in a different way. And it really came at a good time where it would screw with everybody’s sense of self. At an early time in your career that’s a good thing and I think the band really embraced that. None of us were too entrenched in thinking we needed to be bigwigs. What Bruce was doing was adding a theater of the absurd but creating an environment that was a self-reminder of having good intentions when you go out there and playing with intention…and keeping your ears open and trying to keep your ego at bay, you’ve got enough members in the band.

John Popper: They had the reverence of all the musicians. They did kind of embodied the spirit of the H.O.R.D.E. movement, at least among us. They were an empire within an empire.

Oteil Burbridge: That whole time was so surreal because the ARU was the first time that we purposefully started a band with no hope, and therefore no intention of doing anything but scaring normal people away. We certainly never expected in our wildest dreams to get a record deal or be invited to be on a big tour. The people in those bands were so kind to us. They were our saviors. They flew our flag far and wide and took us under their wings. For them to believe in the absolute madness that we staked our entire lives on moves me in a way that I can’t really put into words.

John Popper: H.O.R.D.E. was laden with mitzvahs and you got them done back to you. There was such good will on that tour.

With some of the preliminaries resolved, the next action item became finalizing the name of the tour itself. John Popper’s suggestion demonstrated his unique perspective on what this would all represent.

John Popper: I was into Attila The Hun, so here’s my fantasy. For some reason it’s got to be a town in the Midwest because that’s how big our armies would be. A storm comes rumbling from the East and here comes Blues Traveler’s fans…and from the West come Phish fans…and from the South it’s Widespread fans…and from the North it’s Spin Doctors fans. So the town is converged upon by a hippie gang. All the food in the area gets eaten up by these people. I wanted it to sound like some sort of Mongol horde. It was originally going to be Horizons of Rock Developing East Coast because that seemed to be an identification of a scene but Eric Schenkman wisely said it should be Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere. And sure enough the next year we started using band like the Samples from Colorado and that would have sucked if we had to make an alteration letter. Decorum is everything.

Not everyone was sold on it, however.

Page McConnell: In a lot of ways Popper was driving the boat in terms of arranging the meeting, putting it together and even the name H.O.R.D.E. Mike [Gordon] came up with a slew of hilarious names and he read out some of them at the meeting. He’s got a knack for funny names and I can remember a couple off the top of my head from 20 years ago: Rock Donkey Dunkle and East Coast Rock-a-Sooey.

After Gordon returned home he drew up an extended list that he circulated sent via fax. The options also included: The Farm-Fresh Banana Festival, The Sir James Isaac Newton Summer Jam, East Coast Diner Poached Egg Music Fest, Seven Hours of Noise, Saltwater Taffy Twisting Machine Festival, Marshmellow Music, Five Bands That Stink, Summer Glacier Meltdown and Big Big Spinach Rock Party. One last minute addition was The Clifford Ball. The name appears with an asterisk and a note on top that explains, “Clifford Ball’s name was on a plaque in the airport. We saw the plaque while finding a phone to call John Popper. ‘A Beacon of light in the world of flight.’ We can get more info on this guy and recreate his world.” Still, recreating the world of Clifford Ball was not exactly what Popper had in mind.

John Popper: They were at some airport and they just read these facts about this pilot and they wanted it to be the entire theme of the tour. You gotta give it to them for abstract. I suppose there’s something special about the Clifford Ball that put the hook in them.

Widespread Panic circulated its own list that included such names as: Deli Tray, Trust Fund Hobo Fest, Cavalcade of The Large, Corn Dodgers and Summer of Flesh. The group also threw its support behind some of the Phish suggestions as well as ARU’s We Aren’t The World before concluding, “Widespread Panic does like The Great American HORDE, without shame.” Still, there was something so special about the Clifford Ball that manager John Paluska, sent one final fax making a case for the name, with an accompanying piece of artwork created by Jim Pollock.

Page McConnell: I don’t think we wanted to take it so seriously and Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere…But it was fine. We weren’t up for a fight. We were happy to be part of it and we enjoyed hanging with all those guys.

With the name resolved, the other lingering issue was who would pay the upfront costs for renting trucks, production and all sorts of requisite gear.

Dave Frey: Nobody wanted the risk, everybody just wanted to be paid to show up like they normally would at a gig. Blues Traveler said no and the people at Bill Graham Presents said no. So John and I said yes and we started a company to become the place where the rubber meets the road. While they were somewhat late in the game in terms of securing summer amphitheaters, the H.O.R.D.E. core eventually convinced 8 promoters to commit (four in the north and four in the south). So on July 9, the H.O.R.D.E. Tour finally kicked off with a performance by Col. Bruce Hampton and the Aquarium Rescue Unit that was equal parts visual spectacle and musical virtuosity or perhaps it was visual virtuosity and musical spectacle.

John Bell: It wasn’t like you were listening to songs, it was like all of a sudden you became immersed not only musically but visually. You’re hearing this music which is basically rock and roll format but it was turning into jazz that could go anywhere at any time and improvisation at its highest and the next thing you know Col. Bruce is body slamming Oteil the bass player and you go, “Wow that just happened but the music is still seamless…”

Speaking of seamless, at the close of ARU’s set, the members of Widespread Panic gradually joined them on stage with all the members of both groups performing together for a stretch before the Unit dispersed, one at a time. As I watched this take place on H.O.R. D.E’s opening night it felt almost like a political statement, in asserting the common spirit and intents of the participants. As it turned out, it was less about politics and more about play.

John Bell: It really started because we saw an extra 15 minutes instead of doing the changeover. We saw the 15 minute window as an opportunity to do something different and continue to play and keep the music going. You really couldn’t do it unless you had the larger stage and a bunch of young crew members willing to go, “Whoah okay this is freaky, yeah let’s do it.” We wanted to stretch the usual parameters of normality in going to a concert. The other bands and managers were wondering what the crap was going on. “Well you know, it’s our time…”

Oteil Burbridge: That was so cool, I thought. I still have a photograph of one of those moments [at Garden State Arts Center]. I think Popper was sitting in with us at the time too, so we really had three

bands onstage. It’s always fun to mix things together like a gumbo. And we’re all huge fans of everything New Orleans. That was the spirit of that whole tour, the mindset. In retrospect it was so cool to be able to make your own rules, let your imagination go a little more. That is something that I think jambands have excelled at. Just being open.

The evening continued, with the Spin Doctors, now enjoying some unanticipated mainstream recognition with the success of their single “Little Miss Can’t Be Wrong,” followed by Blues Traveler and then Phish. All three of these sets offered standout moments and the night had served the larger purpose of demonstrating the collective draw of such a bill while allowing the acts to perform on a larger stage.

Mike Gordon: I think that was our first arena gig, which was sort of a nice way to do it. With Phish we always cruised slowly. So even though we normally didn’t team up with other bands to do tours, getting our feet wet in an arena and seeing what it was like without having to carry the show by ourselves, that was a good opportunity for us.

Chris Barron: It was big. We tried to set up close to each other. Our crew set us up in proportion to the stage and we were like, “No, put us back close together.” It’s weird being that far apart. And our drummer pointed out that Led Zeppelin did that. No matter how big the places they were playing, they always set up the way they would in a club. I definitely remember feeling a little agoraphobic and naked and exposed on this great big stage but getting used to it and enjoying the freedom, enjoying having a little bit of room.

As the H.O.R.D.E. traveled west, Portland proved to be the lone show of the first four not to sell out. The bands traveled to Empire Court at the New York State Fairgrounds on through blow out nights at the Garden State Arts Center and Jones Beach. The GSAC show featured a gag that spawned a sequel the next year.

John Popper: We set up a trampoline that was rigged to break when Phish does “You Enjoy Myself” and they jump on the trampolines. They start playing the song, they bring out a third trampoline and then I come out. “Oh my God, Popper’s going to do the trampolines with them.” So then I jump through it and it breaks and I walk off all dejected. It was a nice gag and it came off without a hitch. We’re pros, I’m honored to be part of a Phish sketch and everybody for the rest of the year is going, “Popper I saw that show, don’t worry man, those trampolines are fragile.” They thought that I really was going to do it and it broke. They didn’t know that it was rigged to break, so that bothered me for a whole year.

So the next year I’m a wheelchair because I broke my leg and we get a giant yard trampoline rigged to break and we get a dummy and dress him in my clothes and we get a wheelchair and dangle it from the ceiling. We’re in Richmond, Virginia and we’re running low on time. At the very end I’m playing off stage with wireless mic as they lower what looks like me from the ceiling swinging from this line in my wheelchair playing. Then the cord gives way and I fall though the yard trampoline. But as it happened we were just out of time so the lights came on as soon as I fell through the trampoline and it looked like something really horrible has happened and I’m off stage going “I’m alright, it’s okay, oww, oww…” It was the only time I ever made Trey laugh with like snot coming out of his nose. I was very proud of myself because I was trying to impress Phish with my skit abilities and for many years it was, “I was at that Richmond show are you okay?”

The Phish set that night also featured one of the curious elements of that initial tour, in which a number of official H.O.R.D.E. dancers came on stage during “The Landlady.”

Geoff Trump (Tour Manager): We incorporated these twirling dancers into the audience. We asked them to dance in the aisles so that the members of the audience wouldn’t feel so restricted and they’d get up and dance too.

Shortly after its inception, H.O.R.D.E became something more than just a platform for five bands to appear in amphitheaters. The H.O.R.D.E. Concourse presented a variety of social and environmental awareness groups. However, at the Garden State Arts Center and then Jones Beach, three of these organizations, NOW, NORML and Planned Parenthood were banned, due to a purported policy regarding political advocacy groups on public parks. After H.O.R.D.E. gained leverage for its second year, these conflicts abated. Any such drama eluded the musicians as they settled in.

John Bell: The dressing rooms were nicer, catering was existent but the best element was that we as Widespread Panic were young enough to want to be out and involved and co-mingling with all the other musicians in a social way as well. Kind of like what you would see in some of movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s that were trying to document behind the scenes at rock and roll events. People were just getting together and spontaneously playing songs with each other, doing press together. And we were young enough that we weren’t trying to protect our personal time or anything. Everything was wide open.

Chris Barron: The Colonel was always somewhere prognosticating and prophesying and I really liked him a lot. He was such an interesting guy. [Blues Traveler bassist] Bobby Sheehan was such a ubiquitous presence. He was everywhere at once and a magnanimous host. I also remember Phish had a dog on their bus and I thought that was really neat. The different band cultures were really interesting. Like we never would have had a dog on our bus but those guys did and it was cool. There was also just really cool music everywhere. On stage and back stage people comparing notes and playing guitars. It was neat. I wish I had the gumption to try to write with a lot of those people. I wanted to ask everybody, “Hey, let’s try and write a tune” but I was too shy.

Eric Schenkman: I remember spending some time with Mikey [Houser, Widespread Panic guitarist]. There wasn’t the Internet and all that, so here’s this cat from Athens speaking the same language as me. I was just really interested to talk to the other guitar players, talk that language and there was a lot of cross-pollination in that.

Mike Gordon: I still have pictures of us hanging in the hotels.

The first leg concluded at Jones Beach, which featured a bonus full band segue as the Spin Doctors’ performance led into the Blues Traveler set, something they had done previously at Wetlands Preserve but never before so many people.

Chris Barron: It was really neat to be on stage and then out comes John Popper. “Oh, that’s really cool,” and then out comes Chan. “Holy shit, what the hell?” Then you have two bass players, two drummers… “Wait

a minute, both of these bands are on stage playing!” It was a really cool thing to be part of and to do it at Jones Beach at the H.O.R.D.E. was pretty classic.

H.O.R.D.E then slumbered for a few weeks, resuming at the Oak Mountain Ampitheater in Pelham, Alabama, on August 6, followed by stops at Lakewood Amphitheater in Atlanta, Charlotte’s Carowinds Palladium Amphitheatre and finally, the Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Maryland. While none of these shows were sellouts, nearly 12,000 fans made it to Lakewood. Phish had opted not to appear on the southern shows, so their slot was filled by Bela Fleck and The Flecktones.

John Bell: When we did the southern run with Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, we were like, “Holy crap, there are other bands that embrace this Aquarium Rescue Unit kind of mentality. To watch the Wootens, the combination of technical ability and improvisational and intuitive skills was just off the charts. It was great to be able to play your set and then watch this stuff go down. It felt really good.

Chris Barron: I got a huge kick out of Futureman because every night before they would go on he’d be taking that thing [the drumitar] apart. They’d be just about to introduce them and he’d have the thing in pieces. He’d have it on him but he’d have a screwdriver and the cover would be off it. Bela was like, ‘He does this every night. He always seems to get it together by the time to go on but every night he has the thing apart…”

John Popper: That harmonica player Howard Levy, he was just a freak. He is I think the best harmonica player on earth on the blues harp. I saw him do something that I never saw anyone else do on a harmonica. You know how someone has a left hand on a piano and a right hand, he can do those independently of each other. We did a jam together and I had to go where he wasn’t because what do you when someone can play chromatically on a blues harp and I can’t. I had to go rhythmically so I was being more of a percussion instrument and he was doing a melodic thing, so I could go places he couldn’t go. It was a great little dance back and forth.

Bela Fleck: I remember jamming backstage with Matt [Mundy, ARU mandolin player] and the most epic jam ever on the last night at Merriweather Post. We all got out there, and John Popper said “This is called E!” Then we went wild for 20 minutes on E.

Even though H.O.R.D.E. was pretty much a wash that first year in terms of the festival’s finances, it had done well enough and the performances were certainly spirited enough to warrant a second go-round in 1993. Promoters had been somewhat wary of the tour, giving only minimal advances to the participants but the solid gate receipts allowed the groups to reap unexpected benefits.

Dave Frey: That’s the thing with promoters. If you’re expected to fail and you walk out with a lot more money than anybody ever thought you would make then that gets everybody on their ear. So it set us up for the next year.

Of course, there was more than just that validation.

Chris Barron: For all those bands it was a moment to look around and say, “Hey, we’re not just standing on a cliff somewhere screaming out into any empty canyon. There are people out there who want to hear this kind of music. There are other bands that want to play this kind of music and we’re not just these Jerry Garcia, Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman disciples banging our heads against the wall in the dark somewhere. This is actually something that has a place and an opportunity for us to take the music down the road a little further in our own way.

John Bell: If you look into the future the legacy took hold with things like Bonnaroo. I give the Bonnaroo guys full credit for just knocking it out of the park right off the bat. I know what we were feeling when we were doing the H.O.R.D.E. that was embodied in the Bonnaroo situation. And there are a number of other festivals around the place that are cultivating the same vibe.

Page McConnell: I don’t know if the term jamband was really thrown around much before then but it did somehow solidify the genre in people’s minds—if not in my mind, then at least in people’s minds. And in my mind it was recognizing that yes, there’s something going on out there that’s bigger than us.

John Popper: My favorite moment that first year is a weird one. After the show in Lakewood Ampihteater in Georgia. I’m leaving and I haven’t eaten yet, so we hit a Burger King and they’re out of food. That to me was one of the best moments of HORDE. You come into a town and their fast food joints are empty. That was as close to the reality and the imagination coming together in my bizarre Attila the Hun fantasy, that Burger King in Georgia.