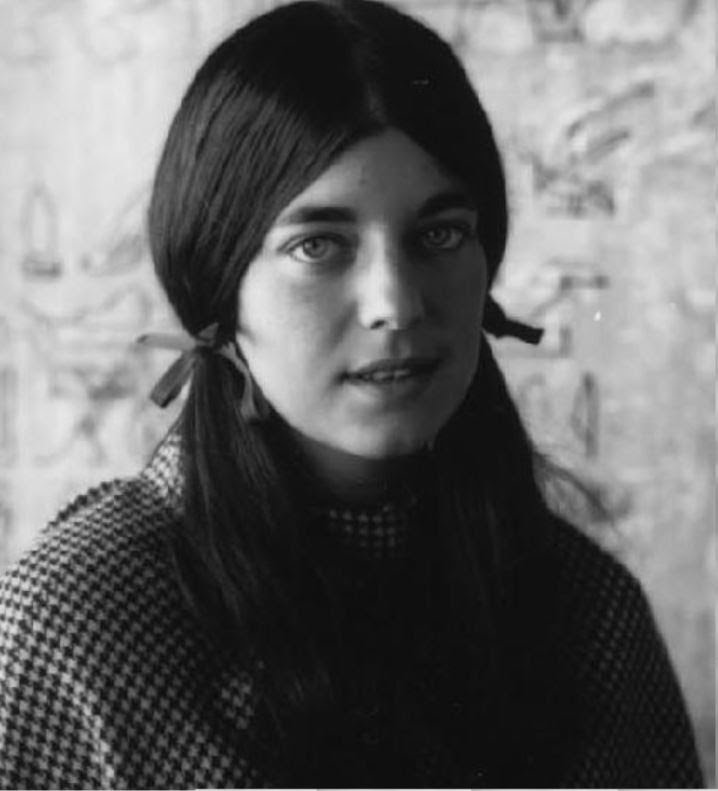

Whether by coincidence or some trick of cosmic fate, Signe Toly Anderson Ettlin, the first female vocalist in Jefferson Airplane, died January 28, the same day as fellow co-founder Paul Kantner. Like Kantner, Ettlin was 74. The official cause of death has not yet been revealed but Ettlin—who was known as Signe Anderson during her brief tenure in the band—had only recently entered hospice care, following a long illness.

Born Signe Ann Toly in Seattle on Sept. 15, 1941, and raised in Portland, Ore., Anderson (who took the surname of her first husband, lighting engineer Jerry Anderson) was a secretary moonlighting as a folk singer in San Francisco when Marty Balin, who had initiated the concept of Jefferson Airplane, and Kantner approached her to join their fledgling outfit. “Marty heard me and said, I like that voice. I want that voice,” Anderson told this writer, recalling her introduction to her future collaborators.

“One sweet lady has passed on,” Balin wrote on his Facebook page following Ettlin’s death. “I imagine that she and Paul woke up in heaven and said, ‘Hey, what are you doing here? Let’s start a band.’”

Balin, Kantner and Anderson, along with guitarist/vocalist Jorma Kaukonen, bassist Bob Harvey (soon replaced by Jack Casady) and drummer Jerry Peloquin (replaced early on by Alexander “Skip” Spence, then other drummers), made their debut as Jefferson Airplane at San Francisco’s Matrix club (co-owned by Balin) on August 13, 1965. The folk-rock group’s immediate popularity sparked a new, vibrant music scene in the city that would quickly mushroom as other now-legendary bands—the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother and the Holding Company and Moby Grape among them—ushered in the era of psychedelic rock.

Within the original Jefferson Airplane, Anderson played a vital role, both as harmony singer and lead vocalist. Her rich, blues-informed voice was most prominently heard up front on “Chauffeur Blues,” a song—originally performed by Memphis Minnie—that appeared on Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, the band’s 1966 debut album, the only one on which Anderson appeared.

Anderson ultimately stayed with Jefferson Airplane slightly more than a year, a time infused with tension between the band and its first manager, Matthew Katz. Katz, who arranged for the Airplane to sign with RCA Records and booked the band’s live appearances, had signed each musician in Jefferson Airplane to individual managerial contracts later deemed by the courts—after an epic, precedent-setting 22 years of litigation—to be grossly unfair to the band members. Anderson, at the urging of her husband, had refused to sign, causing delays in the recording of the debut album. “They wanted so bad to have that money,” Anderson told me in an interview, “that they signed and never read [the contracts]. I read the entire thing. And I went, ‘No, no…Wait a minute, you’re not gonna get away with this crap.’ That put a bad bond in between the boys and me.”

Anderson did eventually sign Katz’s contract, and work commenced on the album in December 1965, but soon compounding Anderson’s tenuous position within the Airplane was her pregnancy. Even as the group gained in popularity and the San Francisco scene itself took off, it became evident by the fall of 1966 both to her and the others that Anderson would not be able to stay. Her final performance with Jefferson Airplane came on October 15; Grace Slick joined the next night.

After leaving Jefferson Airplane, Signe Anderson returned home to Portland, where she raised two daughters, Lilith and Onateska. She divorced her first husband in 1974 and married building contractor Michael Ettlin three years later. (He has since passed away as well.) Although she never achieved the level of fame enjoyed by her former bandmates, Signe Anderson Ettlin sang with a local band, Carl Smith and the Natural Gas Company, and on occasion made appearances with Kantner’s post-Airplane outfit Jefferson Starship. Most of her post-JA time was spent working various jobs and parenting, however.

“She was our den mother in the early days of the Airplane,” wrote Kaukonen upon Ettlin’s death, “a voice of reason on more occasions than one…an important member of our dysfunctional little family.”

No Comments comments associated with this post