One of rock music’s great virtues is its ability to reinvent itself. To build on what has come before, reimagine it and create something new. That process has been in full flower lately, as a host of newer and younger bands lean back toward a sound that first blossomed in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, with the rise of the singer-songwriter and the more pastoral sound of artists ranging from Simon & Garfunkel and the Byrds, to Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. It’s often referred to as the Laurel Canyon sound, after the region of Southern California where many – but not all – of these artists congregated.

It was a sound that featured gorgeous harmonies, poetic, almost confessional lyrics, and a countrified, back-to-nature sensibility – though most of its practitioners came from the big city. And it’s a sound now being reimagined by artists ranging from established bands like My Morning Jacket and The Decemberists, to newer groups like Band of Horses, Dawes, Mumford and Sons and The Belle Brigade.

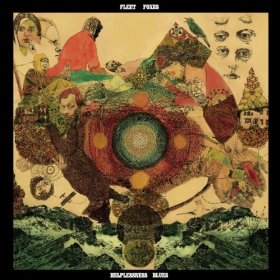

But perhaps no band has made the reconnection with this sound more directly than Fleet Foxes. Their latest release, Helplessness Blues, is the long-awaited follow-up to the band’s eponymous 2008 debut. The new album, which took some two-plus years to write and record, has all the makings of a classic – it’s a beautiful, finely crafted piece of work that is even stronger than the group’s widely praised first album. Like many a classic, it’s an album that draws inspiration from and carries echoes of other artists, and other times.

The group’s lead singer and songwriter, Robin Pecknold, has cited many other artists as inspiration for Helplessness Blues, ranging from Peter Paul & Mary to Bob Dylan, The Byrds, Neil Young, CSN and Van Morrison. Pecknold has said they were aiming for something akin to what Van Morrison pulled off on his seminal Astral Weeks, and while Helplessness Blues doesn’t really sound like Astral Weeks, it feels like that album. The songs are intensely personal; they seem to flow out of some waking dream-state; they repeatedly harken back to childhood and self-identity; and they ignore traditional song-writing rules with impunity, shifting rhythm and pace at will, trailing off at times in mid-thought.

But the real parallel – not just in terms of sound but songwriting as well – is with Simon & Garfunkel and CSNY. The strongest songs on Helplessness Blues all carry echoes of classic Simon & Garfunkel and CSNY tracks from the late ‘60s or early ‘70s.

One could drop Simon & Garfunkel’s “America” into the middle of Helplessness Blues and scarcely notice they were recorded 40 years apart. The sense of dislocation that Pecknold evokes on the jewel of a title track rivals the aching loneliness that underpins Simon’s earlier song. Fleet Foxes may not have the self-confidence to actually title a song “America” – it’s surprising that Paul Simon was able to pull this off, in 1968 of all years, without falling victim to preachiness or smug self-righteousness – but they are writing songs almost this good.

Other tracks on Helplessness Blues – “Sim Sala Bim,” “The Plains/Bitter Dancer,” “The Shrine/An Argument” – call to mind a certain strain of Crosby, Stills & Nash at their high harmonic best, embodied in songs like “Guinnevere,” “Helplessly Hoping,” and “Cathedral.” Of course, CSN had the benefit of three accomplished songwriters – however mixed a blessing that proved – while the 25-year-old Pecknold shoulders nearly all the songwriting duties for Fleet Foxes himself, a fact that makes the strength of this album all the more impressive.

Second albums are notoriously tricky, deflating countless up-and-coming bands that seem poised to hit the big time on the basis of a promising debut, only to be brought down to earth by a lackluster sophomore release. All the good songs they had nurtured on the way up have been used, and the process of coming up with an entire album’s worth of new material finds them wanting.

That is not the case with Helplessness Blues. Although by all accounts the crafting of this album did not come easy for Pecknold and the rest of the band, the end result is an album that sounds as if it flowed out effortlessly and was recorded in one long session. Carried along by its harmonies, it feels seamless and utterly cohesive.

The point of calling attention to the connections between Helplessness Blues and the songs of an earlier era isn’t to pigeonhole Fleet Foxes, which I’m sure they’d bridle against, but to say they are getting to be that good. The sound of Helplessness Blues is wholly new, and wholly their own, but it has its roots in some of the best folk-pop of an earlier era. If it had been released in the late ‘60s or early ‘70s, it would quickly have become a classic. Unfortunately it’s much harder in a fragmented music industry to have that kind of success anymore. That’s too bad. This is a great album, and deserves to be heard by as many music fans as possible, old and young.

No Comments comments associated with this post